"Remember: our life does not turn on trivialities, but on the stars."

"Remember: our life does not turn on trivialities, but on the stars."

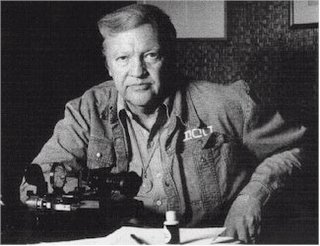

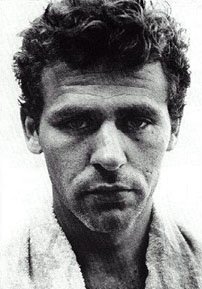

My, I can see I unleashed a little firestorm with my last post on James Dickey. A debate has arisen concerning Dickey's view of the poet's status in the universe. Does Dickey think he's superior to others, or not?

First, I think I may have done Dickey a disservice, posting that speech without providing relevant commentary. I'd like to provide some now, although I will admit, I'm dealing with some pretty heavy material in my studies of Agee, Wright, Bly and Dickey, some big thoughts that I haven't managed to completely wrap my mind around yet. Which is probably why I didn't include commentary on the Dickey speech in the previous post: I hadn't absorbed it yet. In other words, without being quite aware of what I was doing, I was posting Dickey's words so I could truly see them and reflect on them. I hadn't considered they could actually offend my readers' sensibilities.

Second, I think it's important to reveal at this time that I came to Dickey through reading James Wright's letters. Some of you recall that I took a river journey this past summer which lasted two months. One of the stops on the journey was Martins Ferry, Ohio, where Wright was born. I took Wright's collection of poems with me on the trip and bought Wright's letters when I returned home, after seeing the letters reviewed in

The New Yorker. Wright's and Dickey's correspondence intrigued me. I was impressed at the volume of the letters they produced and at the quality of thought in them. I recently found the collection of Dickey's letters on Amazon and have just started reading them.

Third, Dickey's letters come to me at a time when I've been searching for what it means to be an artist. Those of you who have been following my blog know that I've been wrestling with my thoughts on writing and the creative life the whole time I've been blogging. I'd been wrestling with these thoughts much longer than that. At least now I've decided that I am indeed "an author," but what does that mean? What is the artist's relationship to the world? To understand the role of the artist, I've been avidly reading what artists have had to say on the matter.

My point of intersection with Dickey is in how he viewed the poet's work as a divine act. In my reading of Wright, Dickey, Bly, and Agee, I've come to understand they were very serious about their art. Wright, Dickey, and Agee were troubled men. They all drank heavily and suffered all manner of depression, alienation, and heartache. I don't think it would be exaggerating to say it was poetry that gave these men the only sense of freedom they had ever known. They were not religious in the conventional sense, but they felt the divine through their art. It's frankly quite amazing to me that I could have anything in common with these hard-living, driven men. I once thought my attitude of art's connection to the divine was feminine or soft. Seeing the attitude expressed through a strong male figure like Dickey shows me my thinking was wrong.

For these men, the poetic consciousness gave them a faculty through which to perceive the spiritual world. It gave them, they thought, an inkling into a world of "Divine Wisdom"--the world of the Sophia. Their work looked into the darkness, and, like Novalis, they saw in this darkness the great mystery of life. Their art was their way of overcoming death because through their art, they believed they had tapped into something eternal.

Novalis was a German poet living at the end of the 1700s. He had a spiritual vision at the grave of the woman he was to marry, and in this vision he came to understand the value of darkness and the mystery of life. Novalis wrote:

...then, out of the blue distances, from the hills of my ancient bliss, came a shiver of twilight, and at once snapt the bond of birth, the fetter of the Light. Away fled the glory of the world, and with it my mourning; the sadness flowed together into a new, unfathomable world.

I think Dickey, Wright, Bly, and Agee also had this vision. They may have experienced it in a different way than Novalis did, but their insights were hard won through a series of falls, sufferings, and finally a kind of resurrection through their art. Certainly, Dickey and the others were drawn to poets like Novalis, de Nerval, Neruda, Trakl, and Vallejo, poets who had entered this darkness either through suffering or madness, sometimes both.

This, I think, is what Dickey means when he says the poet is elevated. This poet-seer, through art, has access to the great mysteries of life, what Dickey refers to as "the secret." It's this mystery that Dickey elevates above the trivialities of culture, the schlock culture, along with its "general icons." It may help to know that Dickey worked in advertising for a while in order to pay the bills. In one letter, in fact, he draws a distinction between a Coca Cola ad he was working on and Shakespeare. Coca Cola is a general icon. Coca Cola is schlock. It isn't on the same plane as Shakespeare, or de Nerval, or Novalis. Coca Cola is not divine, in Dickey's view.

"Away fled the glory of the world," Novalis wrote. In other words, Novalis had seen "the secret" and nothing could compare.

To further illustrate what Dickey may have meant by poets being "up there" and general icons being "down there," consider something that Wright wrote to Robert Bly: "You know, I sometimes try to escape the thought, but it returns and returns and returns: that some day I shall rise at morning and simply walk outside and away, leaving everything behind, like Buddha. Yes, I shall be killed by a runaway checkbook or an insane life-insurance policy by the time I get two blocks from home."

I speak of Wright, Bly, and Dickey almost interchangeably because they were poets during the same time and were great friends who corresponded about art over a long period. They helped sharpen each other's thoughts. Wright made the comment about Buddha and life-insurance, but Dickey could just as well have. The runaway checkbook and the insane life-insurance policy are those killing forces Dickey was talking about. They are "down there," that is, trivial considerations compared to "the secret."

In Dickey's own work, his poetry and his fiction, we see a that mystery being played out through encounters with nature.

Deliverance is the example most people will remember. In that novel, the river is a force that humans seek to "beat" or to "control." But Dickey believed the mystery could not be controlled, and only those who didn't understand the mystery sought to control it. Humans try to put themselves above the mystery, or "the secret."

At the beginning of this post, I included a quote from one of Wright's letters, a letter he wrote to a despairing friend. Wright and Dickey wrote many such letters to poet friends, letters of encouragement.

Wright wrote to his friend: "Remember: our life does not turn on trivialities, but on the stars."

I think this is what Dickey was saying.

There's poetry in everything. A poem isn't just a series of words, lines, or stanzas on paper. The river is poetry; a potato is poetry. A tree, a rock, the sky, a crow, a mermaid, the turkey shit my mother used to spread on her garden (which, by the way, she said was "like gold.") If you could read Dickey's letters, and Wright's, I think you'd see the absolute humility they had when it came to their role as artists. They were in complete awe of poetry and felt their inadequacies acutely.

I hope I've clarified a few things for my wonderful friends and readers. Like I said, I've only begun to scratch the surface of these mysteries myself. The picture of Jesus is one I've posted before, back on my AOL blog. It was posted on one of the first entries I did. When I posted that picture of Jesus so long ago and called it "My Writing Life," I had only the vaguest notion of what the implications of that picture were. I think I'm getting closer to understanding what "My Writing Life" does indeed mean. Bear with me as I continue my search.