Saturday, December 30, 2006

Making Space

Some of the reference books can be taken to my office. After doing some thinning out and rearranging there, I found I have a whole shelf for wayward books. But many of my books are going to need to either be given away or taken to the Goodwill or the used bookstore. What a job this is going to be. I am reminded of a poem Donald Hall wrote after the death of his wife, Jane Kenyon. In it, he spoke of gathering books that had been bought with such high hopes, many never read, and boxing them up to discard them. I feel the same sadness and hopelessness as I go about this task, but I know I'll feel better when I've carted off many of my books and created around me the library that I need right now.

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

Shedding Some Light

Photo: One of Philip Guston's lightbulb drawings. As a child, Guston used to hide in his closet and draw pictures. Doing so calmed him and made him happy. The lightbulb image is a manifestation from his closet. He replicated the lightbulb image in several paintings and drawings throughout his lifetime.

Photo: One of Philip Guston's lightbulb drawings. As a child, Guston used to hide in his closet and draw pictures. Doing so calmed him and made him happy. The lightbulb image is a manifestation from his closet. He replicated the lightbulb image in several paintings and drawings throughout his lifetime.I also reread one of the texts I'll be using in my seminar next semester, Gregory Orr's Poetry As Survival. Orr experienced a psychic wound as a child when he accidentally killed his brother in a hunting accident.

In Poetry As Survival, Orr writes: "To say that I was horrified and traumatized by the event is only to state the obvious." The point, says Orr, is that his writing got him beyond the horror and the paralysis.

Of course, it isn't enough to have a psychic wound and to write about it--great writing comes about only through a careful and (usually) long apprenticeship, Orr explains.

The first half of Poetry As Survival explains the psychology of writing and healing. Orr's writing is thoughtful and engaging. He has the ability to explain complex concepts in a way that is easy for the reader to understand. For instance, in explaining the "self," Orr writes: "The self, in my image, is like a tiny island in a vast sea of chaos, and it's also like those conch shells you lift to your ear to hear the ocean's roar: the chaos of the sea is inside the self also."

Throughout, Orr seeks to explain how writing can give order to the seemingly chaotic life.

The second half of the book deals with writers of the personal lyric, focusing on early practitioners like Blake, Wordsworth, and Whitman. In addition, Orr writes of several poets as being his "heroes." In doing so, amazingly, he humanizes them, makes them real people rather than the marble statues they seem to be in poetry anthologies.

Other poets Orr discusses are: Plath, Roethke, Dickinson, Keats, and Wilfred Owen.

One of my favorite revelations in the book was Orr's brief discussion of the Polish poet Tadeusz Rozewicz, whose "In the Middle of Life" portrays, in Orr's words, "a shell-shocked, traumatized veteran who must relearn everything from scratch and through elementary incantatory repetitions." Here is a selection from Rozewicz's poem:

After the end of the world

after my death

I found myself in the middle of life

I created myself

constructed life

people animals landscapes

this is a table I was saying

this is a table

on the table are lying bread a knife

the knife serves to cut the bread

people nourish themselves with bread

one should love man

I was learning by night and day

what one should love

I answered man

this is a window I was saying

this is a window

beyond the window is a garden

in the garden I see an apple tree

the apple tree blossoms

the blossoms fall off

the fruits take form

they ripen my father is picking up an apple

that man who is picking up an apple

is my father

I was sitting on the threshold of the house

that old woman who

is pulling a goat on a rope

is more necessary

and more precious

than the seven wonders of the world

whoever thinks and feels

that she is not necessary

he is guilty of genocide ...

It is intriguing how that last stanza has parallels to McCarthy's The Road. The great battle in The Road is how to keep your humanity in the face of overwhelming loss, fear, and senseless killing. The Road is not a Science Fiction tale: it really is a book about how we deal with life every day, the extent to which we allow ourselves to become genocidal in our thoughts--whoever thinks and feels/that she is not necessary/he is guilty of genocide. So it shouldn't be surprising that Rozewicz's poetry and McCarthy's book would say some of the same things: Rozewicz was writing in the aftermath of WWII horrors.

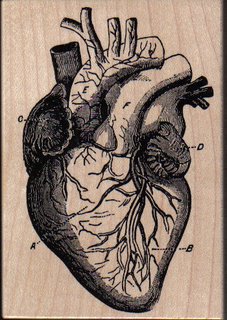

One of the reasons I want to do the seminar is because courses in literary criticism erase from consideration the writer's original and personal motivations for writing. I do think literary criticism is important, but there needs to be balance. Too often, I think, works are treated as cadavers, opened and probed objectively on a slab.

Orr, in contrast, brings poets and their poems fully alive. The experience of reading this book was thoroughly rewarding. Gregory Orr's Poetry As Survival is a great companion to DeSalvo's Writing as a Way of Healing: How Telling Our Stories Transforms Our Lives.

By the way, if anyone runs across a poetry collection by Tadeusz Rozewicz, I'd appreciate knowing about it. I would love to read more of his work.

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Toy Stories, Part III

You would think that since I turned out to be a writer, that writing would have played a stronger role in confessions. I did create newsletters with my friends for fun and enjoyed writing my school papers. But I never kept a diary, though I tried. For many years I couldn't write about my problems. I didn't think they were important enough to devote written words to them. But at night I would pull tiger under the covers with me and I would whisper everything into his ear. His green, glass eyes would stare out unjudgmentally.

I have kept the childhood toys that meant the most to me. I have always wondered why. Now I think I kept them because they have something important to say to me about my imaginative life. I had very intimate and profound connections to my toys. I think in a sense that relationship has been turned over to the writing process now. But the toys, I still love.

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Toy Stories, Part II

Photos: Sameen's project in Women's Studies.

I must admit, I never liked Barbie Dolls. I never had one and I never wanted one. I didn't have anything in common with her at all and she didn't have anything I wanted: the fast-paced life, the fakey-looking boyfriend, the glitzy clothes, the pink plastic house. Even her name. Those dolls always had perky names, those "ie" or "y" names, like Barbie and Tammy. I wasn't a perky child. I was calm and quiet. In a group of other children, I'd sit alone and fold my hands in my lap and just observe. I didn't feel lonely or left out. But I did feel different, set apart, and this was a curiosity to me.

I visited a few friends who had a Barbie and watched with curiousity as they played with it. I just didn't get it.

This semester in Women's Studies, a number of my students admitted to having had eating disorders; at least two had undergone therapy for years. Not one of them blames Barbie completely, but Sameen, at least, felt Barbie with her waspy waist should bear at least part of the blame.

I know a number of people will think it's silly to blame a doll. Maybe you had a Barbie and you came out just fine. And, after all, I had a toy turkey: I never wanted to be a turkey, did I? But that would be missing the point; just like we miss the point when we say we play violent video games but never killed anyone. The point is, some children ARE suseptible to these things and we don't know the full extent of these influences yet.

Barbie has been a controversial toy for some time. One of the texts we used in class, now called Body Outlaws, first had "Barbie" in its title. The toy company sued and the author changed her title. However, the critical essay about Barbie remains in the text.

I wonder how many girls will receive a Barbie under the tree this Christmas. There are very few things as beautiful as children playing with their toys. But not all toys are innocent, I think.

Monday, December 18, 2006

Toy Stories, Part I

This Santa is old but he is new to our house. I spied him in the Goodwill the other evening, sitting on the floor next to a big tub of plastic toys.

First, you have to understand something about me: I am not that much for Christmas decorations, especially "cute" ones. I actually dislike "cute" toys all together. Care Bears? Forget about it. Trolls? You're getting closer. Hobgoblins? You're definitely in my territory. Three of my most prized toys are Jack, the mayor, and Sally from The Nightmare Before Christmas.

Back to Christmas: My preference is to decorate as the ingenious peoples of the Pacific Northwest did, with black crows. There is something awesome in the power of crows. In the old origin stories, crow brought back the sun and saved the Earth from eternal darkness.

So this might explain my attraction to this particular Santa; I mean, isn't he creepy? He looks like an evil Gnome in a Santa suit. So many of the toys of the late 1950s and early 1960s had this look. I think they're wonderful.

So there he was, this evil Santa, sitting in the Goodwill, so well taken care of he looks like he came straight out of some grandma's closet. He's a soft stuffed toy, about two feet tall. Looking at him, I could imagine some child many years ago, not unlike myself, carrying him around the house with pride and sleeping with him at night, dreaming of snow and compassion and goodness everywhere.

Santa didn't have a price on him. I said to a woman next to me digging in the plastic toys, "He isn't priced. Do you think he's just here for decoration?"

"That's what I thought," she said. "He's really old."

I set Santa back down and walked away. I walked past him several times, casting longing glances at him. Then Allen walked by, and I said, "Look at this Santa. Isn't he creepy?"

Allen said, "He is that. You want him, don't you?" Allen knows how much I like creepy toys.

I grabbed Santa up into my arms and said, "But I think he might just be decoration."

Allen took him and said, "He's for sale, don't worry."

We went to the check out. The women at the counter commenced oohing and ahhing. They said he'd just been put out on the floor. I started to get nervous. My creepy Santa was creating a great stir. A stranger came up to me and said, "So you're buying the Santa. I was going to get him, just so's to give him a good home."

The woman behind the cash register said, "I can't sell him to you because there's no price on him. It's a new policy. We can't sell stuff's that ain't priced."

Another woman behind the counter picked up Santa and patted his behind. She put him over her shoulder like she was going to burp him. Everybody was falling in love with my evil Santa and I could feel him slipping away.

Allen started getting unnerved. He hates it when I suffer disappointment. He asked what we could do, then. He expressed in clear language that we wanted that Santa, no matter what. The woman behind the register said the only thing we could do was come back the next morning, after he'd been priced and put back out on the floor.

"Okay, but I'm gonna be here at 9 a.m.," Allen said forcefully.

"Well, he won't be out until about 9:15," the woman said.

"Well, that means I'll be here when he goes out on the floor, won't it?" Allen said.

I could tell Allen was getting upset at the thought of Santa disappearing from my arms. He didn't like the Santa, but he knew how much I did.

Back in the truck, Santa-less, Allen and I speculated that: a. Santa would be gone the next morning, or b. the price would be exorbitant.

That night, I looked up my Santa on eBay. One just like him was going for $46.00. I slept fitfully, imagining owning my creepy Santa and also trying to prepare myself for life without him.

The next morning I stayed warm under the covers as Allen slid out of bed and into the cold and dark. It was a bad-weather day, blustery and mean.

I heard the front door close softly, and I knew Allen was out on a mission. I couldn't sleep, and lay there, waiting.

When I heard the door open, I jumped up and there Allen was, holding my Santa. "How much was he?" I asked.

"Two dollars!" Allen said.

"Two dollars! You're kidding!" There it was, the price tag.

I could hardly believe it. Neither (a) nor (b) had come true, so I felt like I'd gotten my Christmas miracle.

Saturday, December 02, 2006

Hy Sobiloff's Child Within

Speak to me child speak to me

You are learning

Yet you may teach me again the sweetness and the curdle

And tell me of the kid that is nursing under the sapodilla tree

And of the seashell I lost

And of those first scenes that I've forgotten

Speak to me of the innocence in the wading pond

That survives somewhere (I shall comment on the miracle)

Open your secrets to me

While I stare at your stare

Show me the buzzard ugly enough to die

The ground dove that has a hermitage

Tell me of the dogs that are better than cats

Cats cannot catch goats

Explain why that child is sitting by the road

Nodding and shaking and no-one there

I shall give you a biscuit

And let you eat it with dirty hands...

Promise me child before you disappear in hide-and-seek

That your next step will be the fiction of this world

That when you leave the broken wall

You will keep your lizard spontaneities...

-----------------------------------------

In 1963, the poet James Wright wrote an introduction to Hyman Sibiloff's poetry collection "Breathing of First Things." In this introduction, Wright seems to chide those who see the quest for the child within as naive or, worse (for Wright), unmanly. Wright says that the rediscovery of what he calls the true self, with its healing powers, necessarily involves a search for the child within, which he equates with the ability to experience wonder through the senses, the ability to see the miraculousness of things, to feel truly alive. In the introduction, Wright says:

"[...] the struggle to be true to one's own self involves a good deal more than the rediscovery of a childlike radiance and joy, though that rediscovery may lie at the end of the journey. The journey itself is a dark one. It is neither more nor less than the attempt to locate and reclaim those healing powers within one's self that are able to provide sufficient courage and literal physical strength for one to confront and overcome the agonies of the world which exists beyond the womb and which, for better or worse, does not happen to be shaped and arranged in a pattern identical with the orchards and rivers and meadows of that earliest garden, sunken now almost below the memory and, whether wasted or redeemed, lost somewhere between the morning of dancing animals and the tousled dusk of sorrowing human faces. Beyond that garden we live a good deal of our death. We may insist on returning to seek it by trying to ignore the shocks and miseries that obstruct the only true way back home; and such evasions really amount to a mere refusal to live. The refusal, the negation, the despair--these are our constant familiar spirits in the twentieth century."

---------------------------------------

Wright describes the journey back to self as a dark one; I think I agree with him. But there are moments of epiphany, of light. An example is found in Sobiloff's poem. The lines in Sobiloff's poem that speak to me the most are: "I shall give you a biscuit/

And let you eat it with dirty hands..."

The reason why those lines are meaningful to me is that I got an immediate image, upon reading them, of myself, very small, innocently eating a biscuit with my dirty hands. I remembered having eaten food with dirty hands, after just coming in from a hard day of play, good play, my hands scooping dirt and all my senses alive, picking up things, exploring them with my hands, feet, and mouth. There is such an honesty in the image of a child with dirty hands. Wright also points out that Rilke understood the power of returning to a child's wonder: "'Every door in me opens,' said Rilke, 'and my whole childhood stands all around me.'"

In one of Wright's own poems, "The Journey," in the final stanza, he writes:

...The secret

of this journey is to let the wind

Blow its dust all over your body,

To let it go on blowing, to step lightly, lightly

All the way through your ruins ...

Such a gorgeous, sensory moment.

I have more to say about this topic, but I need to let my thoughts compost a while longer.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Quotes by Archibald MacLeish

"We are deluged with facts, but we have lost or are losing our human ability to feel them".

"What is more important in a library than anything else — is the fact that it exists".

"A man who lives, not by what he loves but what he hates, is a sick man".

Monday, November 27, 2006

Bars of My Own Body

Photo: Randall Jarrell

Photo: Randall JarrellThe world goes by my cage and never sees me.

--From: "The Woman at the Washington Zoo," by Randall Jarrell

(1960)

--------------------------------------------------

As a freshman in college, I read two poems by Randall Jarrell that I remember: "Death of the Ball Turret Gunner" and "The Woman at the Washington Zoo." I remember getting a great adrenaline rush upon reading about the gunner who hunched in the turret until his "wet fur froze." It is a harrowing poem about the death of a young man, unceremoniously washed out of the airplane's belly "with a hose." Back then, I didn't know poems could be written about such things.

I had almost no reaction at all to "The Woman at the Washington Zoo." I only remember reading it because our instructor, a young man with writing aspirations of his own, loved Randall Jarrell and spoke at some length about him.

Reading "The Woman at the Washington Zoo" this evening, the lines jumped out at me: "Oh, bars of my own body, open, open!" How is it I didn't notice this before, sitting in that classroom so many years ago, listening to that eager young instructor? I wonder.

Sunday, November 26, 2006

My Present Obsession with John Berryman

Photo: John Berryman

Photo: John BerrymanJohn Berryman's life and work have been preoccupations of mine lately. I plan to discuss him in the seminar next semester. As I read about him, I find he is far more interesting to me than I expected he would be. Berryman was intelligent, a teacher and a scholar as well as a poet. He published essays on Shakespeare, which I plan to read over break. Looking at samples of them on Amazon, I saw that he brings a poet's sensibility to Shakespeare. I look forward to reading them. I also ordered a used copy of his letters to his mother (no longer in print). I've seen excerpts and they look fascinating.

Berryman articulated his ideas plainly about what writing meant to him, and it is clear to me that he equated writing with life itself, with his survival. That he did commit suicide in his 60's is regrettable, however not a contradiction, I think. Some people have said he "paid a price" for writing so close to the bone and soul of his existence; rather, I would say it was his writing that kept him alive for so many years (he had also attempted suicide very early in his life).

Berryman's wife, in her book Poets in Their Youth, explains: "It was the poetry that kept him alive... his certainty that there were all those poems still be be written." Always, Berryman was searching for a way to express his "unsayable centre."

Berryman, like John Gardner (author of Grendel), whom I've written about in my blog before because he was so smart and so wild and so authentic, and because taught me everything about writing when I was first beginning, believed that a writer was helped by a psychic wound, a tragic experience that has helped shape the writer's consciousness.

Berryman's psychic wound was the suicide of his father (Berryman found the body). Berryman was named after his father. His birth name was John Allyn Smith, Jr. After his father's suicide, Berryman's mother married her lover, John Allyn McAlpin Berryman and changed her son's name to Berryman. As a result of these experiences, John Berryman the poet would have a lifelong obsession with the idea of identity.

Berryman wrote essays, in addition to poetry, on many subjects, including Stephen Crane and even Anne Frank.

Berryman believed that "the mistress of [Crane's] mind was fear [of abandonment, uncertainty, death]." This statement is important because Berryman believed that writing is a ritual that helps to dispel fear of the unexplainable and the uncertain. He believed that the ritual of writing has power to objectify experience. Through writing poetry, Berryman was able to dispel his own fears and disappoinments.

He also believed that through the ritual of writing, Anne Frank was able to dispel her own fears and create not just a diary but a work of art. He thought that when certain pressures are exerted on writers, their work is elevated to a new, higher level. This is why Frank's diary is more than just adolescent ramblings. Berryman said in his essay "The Development of Anne Frank": "It took...a special pressure forcing [her] child-adult conversion, and exceptional self-awareness and exceptional candour and exceptional powers of expression, to bring that...change into view."

This observation goes along with what Louise DeSalvo says in her book, Writing as a Way of Healing. She says that certain pressures can create a sense of new clarity in our writing.

As Charles Thornbury says, Berryman believed the function of a poem is, in Berryman's own words, "to seize an object and make it visible."

Thornbury says, "The use of ritual--this act of making something visible and thus objectifying it--and what it does for the poet (and the reader) gradually became [Berryman's] fundamental principle."

Berryman also believed that poetry "aims ... at the reformation of the poet." He equates poetry to prayer in this fascinating passage:

"Poetry is a terminal activity, taking place out near the end of things, where the poet's soul addresses one other soul only, never mind when. And it aims--never mind either communication or expression--at the reformation of the poet, as prayer does. In grand cases--as in our century, yeats and Eliot--it enables the poet gradually, again and again, to become almost another man; but something of that sort happens, on a small scale, a freeing, with the creation of every real poem."

With all that said, I'd like to share one of my favorite Berryman poems. It is about, of all things, boredom. I have often wondered whether writing this poem helped to lift Berryman out of his boredom, whether writing this poem was "freeing." We can't know. But I love the poem because it shows me that even great writers like Berryman sometimes feel like hanging it all up and quitting.

John Berryman

Dream Song 14

Life, friends, is boring. We must not say so.

After all, the sky flashes, the great sea yearns,

we ourselves flash and yearn,

and moreover my mother told me as a boy

(repeatingly) "Ever to confess you're bored

means you have no

Inner Resources." I conclude now I have no

inner resources, because I am heavy bored.

Peoples bore me,

literature bores me, especially great literature,

Henry bores me, with his plights & gripes

as bad as Achilles,

who loves people and valiant art, which bores me.

And the tranquil hills, & gin, look like a drag

and somehow a dog

has taken itself & its tail considerably away

into the mountains or sea or sky, leaving

behind: me, wag.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Driving a Pack of Hounds

How shall I tell you how I am reading it? As if I were driving a pack of hounds through a wood, feverishly; only every tree and bush is so unbearably interesting and exciting that I'd like to stop and examine it for a long time, but the hounds are off ahead and won't stop. ... My faculties are raging out in front of me. I haven't felt so powerfully in a long time. Even my unhappiness is acute, sharp, engaging.

Here, I think, Berryman does describe what it feels like to read a great book.

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Note to myself

Photo: A page from Frida Kahlo's Journal

Photo: A page from Frida Kahlo's JournalThis is a note to myself: change the organization of the course, Theresa, so that you avoid the false dichotomy of mind/body. Instead, organize according to the students' required assignments:

(1) Creative Journal (show examples from the Journals of John Gardner, Theodore Roethke, Frida Kahlo, Kurt Cobain, Edvard Munch)

(2) Confession Postcard (show examples from Post Secret, my own postcards, postcards I received in the mail from bloggers and the people I met at Esalen)

(3) Photograph or painting (show examples from Frida Kahlo, Edvard Munch, Vincent Van Gogh, Philip Guston)

(4) Letter (share examples from Donald Hall, James Dickey, James Agee, James Wright, Vincent Van Gogh, Frida Kahlo,)

(5) Poem (share examples from St. John of the Cross, Theodore Roethke, John Berryman, John Ciardi, James Wright, Donald Hall, Robert Lowell, Frida Kahlo, Anne Sexton, and others)

a. Two kinds of poems, personal and confessional. More on this later.

b. Must discuss how to keep from seeming "Angsty" or "self-absorbed." More on this later.

(6) Prose (share examples of my own work, as well as examples from John Gardner, A. W. Frank, Dorothy Allison, James Agee, and others)

a. Prose to be workshopped during final 6 weeks of the course.

b. Three kinds of prose: essay, memoir or autobiographical fiction. More on this later.

Background reading on Art and Healing by: A. W. Frank, Viktor Frankl, Ernest Becker, Rollo May, Louise DeSalvo

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

From Angst to Art: Preliminary Outline

I plan to devote the first 8 weeks to artists and authors whose work was in some way "confessional." The term "confessional" in itself is something we will have to talk about because it has a certain derogatory meaning in academia. Robert Lowell, whose poetry originated the so-called confessional movement, really disliked the term. I don't dislike it because it puts me in the mind of a church confessional, which is a beautiful idea to me. I'm sure the students will have their own ideas.

Part of the goal of this course is to bring the healing aspect of art out of the shadows and give it the respect it deserves. Not only does the concept deserve respect, but I think a course like this could remove constraints students may have placed on themselves regarding their own reasons for making art. Generally, creative writing teachers run from the "art as therapy" idea like the plague because they want to avoid the maudlin-but-it-really-happened syndrome. I'd like to confront the problems inherent in using personal angst as a springboard for art head on, and perhaps offer some insights into how to avoid being self-absorbed. I still need to give more thought to this, especially about the prose I want to bring into the mix, but this is what I have so far:

The class material will be divided into two parts, the mind and the body. Since the students will be sharing their intimate experiences, I plan to also share mine.

I. Depression, Dark Night of the Soul, Mental Illness, Mortality

A. St. John of the Cross

B. Confessional Poets

1. Examples of bad (maudlin) poetry

2. Theodore Roethke/Nijinsky

3. James Wright

4. John Berryman

5. Robert Lowell

6. Adrienne Rich's "Diving into the Wreck"

C. Painters

1. Edvard Munch

2. Van Gogh

3. Philip Guston

D. Stories

1. "Blue Velvis"

2. Secret of Hurricanes

3. John Gardner

E. Non-fiction

1. Rollo May

2. John Gardner

3. Ernest Becker

4. Writing as a Way of Healing, Louise DeSalvo

II. The body: injury, illness, mortality

A. Frida Kahlo

B. Sociologist A.W. Frank, Wounded Storyteller as well as various articles

Monday, November 13, 2006

Creativity is not

Pain of unreturned love...

Sunday, November 12, 2006

On November 12

I've always wanted to teach a course on literature and survival or writing and healing. I don't believe that all artists create because they are striving through their art to be whole, but the artists who are most interesting to me do. For a long time, I was ashamed to admit my writing was a form of healing; I was afraid my work would be diminished in others' eyes because of that. After researching, however, I've become emboldened to talk about it and to weave this philosophy into my teaching.

For a short time, I kept a separate blog on my teaching life. I did this because I felt my teaching life was destroying my creative life. Thankfully, my position at the University has changed, and I'm getting more opportunity to teach literature and creative writing all the time. In fact, after this academic year, I will no longer teach freshman composition at all. I love teaching freshmen, and I don't mind teaching composition, but it's so much work, so much grading, so much attention to technical detail and departmental requirements, that I feel wrung out like a washcloth by the time each semester ends. Now, my "two lives" can become the same, so I will soon be deleting the teaching blog and will talk more about my teaching here.

For over a year now, Roethke's life and work have consumed my attention. I've been on Amazon and ordered every book, new or used, that has been written about him. I'd known his poem, "The Waking" for many years, of course, but I really knew little about Roethke until quite recently. Roethke was a dynamic man, passionate and driven.

When he was in his late twenties, he had a psychotic episode, and he was to continue to have trouble and be in and out of hospitals all his life. He even had shock treatments at one point. Through it all, he kept writing. It has been fascinating for me over the past year to read of how his poetry helped him to know himself better, to tunnel toward the divine. "We think by feeling," he wrote in "The Waking." I remember this line every day of my life because that's how I want to live my life, that's the kind of teacher I want to be.

I love the month of November. The earth goes into hibernation and the rain and snow break down the leaves into mulch for worms. The hardwoods stand naked and you start to get the first really cold days and nights of the season. I wonder what it was like for Roethke, a young man just starting out in his career as a teacher and poet, wandering around on that cold November night, losing his shoe and thinking he'd suddenly found himself closer to God?

Bless you, Ted Roethke, wherever your spirit may be. Bless you and thank you for your poems.

-------------------------------------

From the Literary Notebook:

On this day in 1935, 27-year-old Theodore Roethke was hospitalized for the first of the manic-depressive breakdowns that would recur throughout his life. Roethke had just begun a teaching post at Michigan State University and, according to colleagues, had been drinking heavily all semester, dozens of cups of coffee and bottles of cola a day as well as alcohol. On the previous evening, a cold one, he had taken a long walk in the woods without a coat and eventually with only one shoe; the next morning, after deciding "to cut my eight o'clock class deliberately just to see how long they would stick around," Roethke took another walk in the woods, also coatless. He was shivering and delirious when he arrived at the dean's office, where he planned "to explain one or two things about this experiment"; the dean, trained as a mathematician, called for the doctors. Roethke later told friends that while on his first walk he had had a mystical experience with a tree -- even pointed out the tree, while retrieving his shoe. The tree taught him "the secret of Nijinsky," he said, perhaps referring to that passage in Nijinsky's diary -- written while Nijinsky was a mental patient -- that describes learning from a tree that "human beings do not understand feelings."

Friday, October 27, 2006

It is easier...

---------------------------------------------------------

It's heading into that really busy part of the semester, so I'll probably be posting here a lot less until Christmas Break. I'm doing a teaching overload. I'm also preparing for a seminar I'll be teaching next semester called "From Angst to Art." It's about writing and healing. The quote above, by Rollo May, will figure prominently in the syllabus.

I've been visiting your journals. Some of you are sick, some are well, and all of you are busy.

Sunday, October 15, 2006

A quote by poet Stanley Kunitz

Get Your Nose Dirty

Our sweet dog, Buddha, with an unusual prize, an ear of feed corn from an adjoining field.

Our sweet dog, Buddha, with an unusual prize, an ear of feed corn from an adjoining field.There's a lot of arguing about whether or not people should write every day. Some people feel guilty if they don't. I used to, but I don't anymore. If I write before I'm ready to, I just write junk, and it has no redeeming value at all. I'm not saying that I don't sometimes have to fight fear and procrastination and make myself sit down and write. But I am saying that if my spirit is dry as dust, I know I won't have the energy it takes to write anything good. So I wait. I read, I think, I pay attention.

That's what I mean about Buddha's corn. He paid attention, and he found himself something unusual, something out of his ordinary experience of sticks and limbs and rubber toys. He carried the corn around for a while until it felt like it was really his. He was pretty proud of it, too. He slobbered it up real good. Then when he was ready, he buried it in our field. He dug a hole and then used his nose to push the dirt over the corn. He looked back at us, Allen and I, and this dog's nose was very dirty. He pranced and snorted. He was very content.

So that's what I do, find myself a prize, some unusual happening or observation, a great metaphor that shivers me timbers, and after I've carried it around a while, played with it, pranced with it, ran through the field with it, I bury it for later. I bury it in my memory or plant it in one of my many notebooks or blogs. Then, when I'm good and ready, after other stuff has happened and I maybe have myself a little epiphany, after I understand how special my prize is, I dig it up and use it.

Sure, this is messy. You get your nose pretty diry. It's not systematic. It's not a sure thing. You won't write a ton of books like Joyce Carol Oates does (who, bless her, says she does write every day). But you can go about your days contentedly, searching, like Buddha, for more prizes. Pretty soon, it accumulates. It starts to grow, maybe, green shoots at first, and then a big tall plant. Sooner or later, you'll make that little find into something great. Patience!

Thursday, October 12, 2006

First Snow

For the Woman Out There Who Might Be Contemplating a Great Change

by Lucille clifton

in which my greater self

rose up before me

accusing me of my life

with her extra finger

whirling in a gyre of rage

at what my days had come to

what,

i pleaded with her, could i do,

oh what could i have done?

and she twisted her wild hair

and sparked her wild eyes

and screamed as long as

i could hear her

This. This. This.

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

Handmade Things

I've been thinking and writing about my Ohio River experience, but I've been writing about adolescence, too. It seems that for the last several years, I've focused a great deal on the social and psychological upheaval of adolescence. In a present draft of a story, I have written: "So I hadn't seen Tucker for a week and was sullen about it. But Tucker would follow me to the healing; I'd made sure of that. He'd follow me anywhere because we'd not yet gone all the way."

I have a wicker basket on my hall dresser, filled with my childhood toys. This handmade doll was given to me by my girlfriend, Barbara. We were in the eighth grade when we decided to make each other a doll. This doll she made for me looks just like she did when first made, all vivid yellow and red. The tunic is fastened by little snaps in the back. The details of the face and green hair are heartbreakingly poignant. The doll smiles. Her button eyes are wide with wonder. Within two years, Barbara and I started dating, and we were both married within four.

A lot of my stories seem to grow out of the consciousness from which this doll was made, the borderland between childhood and womanhood. Adolescence is scary and full of change, upheaval. There's something dark and frightening about sex, about losing yourself to another person.

But adolescence also embodies the potential for love. It's all darkness or light when you're that age. Either/or. Looking back on that time with the capability of seeing all the complexities is exciting.

Monday, October 09, 2006

Applebutter Fest

The antique knitting machine that was used to make my socks. Applebutter festival, Grand Rapids, Ohio. Behind the artisan is the canal. In the old days, barges were pulled along the canal by mules, walking the towpath trail. Now, the towpath trail is a hiking trail. It's one of our favorite places to walk. The festival takes place on the banks of the Maumee River.

The antique knitting machine that was used to make my socks. Applebutter festival, Grand Rapids, Ohio. Behind the artisan is the canal. In the old days, barges were pulled along the canal by mules, walking the towpath trail. Now, the towpath trail is a hiking trail. It's one of our favorite places to walk. The festival takes place on the banks of the Maumee River.Allen and I try to go to the Applebutter Festival in Grand Rapids, Ohio each year. I remember we used to take our boys to this festival with us when they were little. There are all sorts of sputtering antique engines, crafts, and, our favorite, the historical reinactments. Every so often, cannons fire over the river, giving everyone a start. The main menu items are bratwurst and saurkraut. This year, I bought a pair of socks that had been made on an unusual antique knitting machine, used during civil war days.

It's past midnight now, and the events of the day are mixing with old memories. I just now read this poem by James Wright:

Trying to Pray

This time, I have left my body behind me, crying

In its dark thorns.

Still,

There are good things in this world.

It is dusk.

It is the good darkness

Of women's hands that touch loaves.

The spirit of a tree begins to move.

I touch leaves.

I close my eyes and think of water.

Saturday, September 30, 2006

Apocalyptic Thinking

Images of war shatter me and move my thinking toward Apocalypse.

I have been asking my composition students to write about the effects of war. I showed them two films, The Grave of the Fireflies and Regret to Inform. Fireflies is an anime tale about the firebombing of Japan during WWII. Regret to Inform is a heartbreaking documentary account of the toll of the Vietnam War on several women, mostly wives, both American and Vietnamese. The stories of the women are threaded together by one American woman's journey to visit the place where her husband, Jeff, died. One of my students, who is a soldier, was very affected by Regret to Inform, saying it has changed everything about his thinking regarding war. After reading his remarks in an in-class writing, I nearly cried.

Papers to grade this weekend and all week long. Papers, papers, papers.

I've been reading so much non-fiction lately that I'm starting to get hungry for fiction again. I just ordered three novels: The Road by Cormac McCarthy, The Echo Maker by Richard Powers, and The Lay of the Land by Richard Ford. I've read McCarthy and Ford before, but not Powers. I especially look forward to The Road. I like McCarthy's dark, Faulknerian view of life and his prose sweeps you away like a rough river. I think all three of these novels may be Apocalyptic in their own way.

Saturday, September 23, 2006

When Nations grow Old...

The Permanent Realities of Every Thing

shall never become a star.

In every bosom

a Universe expands as wings.

This world of Imagination

is a World of Eternity:

It is the Divine bosom

into which we shall all go

After the death of the Vegetated body.

This World of Imagination is Infinite and Eternal,

Whereas the world of Generation or Vegetation

Is Finite and Temporal.

There Exists in that Eternal World

The Permanent Realities of Every Thing

Which we see reflected

In this Vegetable Glass of Nature.

by William Blake

Tombs

In the e-mail, my colleage told me not to bother anymore to read and comment on the story, that she'd shared it with a former professor and he'd told her, pretty much, that the story is rubbish and she should stick to poetry.

I hadn't read the story yet, but now I was really curious, so I got it out of my brief case and read it, and I could feel that familiar anger that has to do with the Tersteegs, the "everlasting no." My colleague's professor had given her awful advice, one of those cold, academic responses that make story-telling sound like some kind of specialized skill rather than an innate need.

So now because of the soul-crushing "advice" she'd received, my colleague was ready to give up on story writing all together. I told her I hope she continues to work on her story, that even if it never sees publication, it's still important that she writes it, that she lives with it for a while, that she gives it a chance before she strangles it while it's still in the cradle.

"Sure," I told my colleague. "There are techniques and skills that we acquire along the way, but not knowing those isn't a reason to stop writing stories!"

It's a lovely story, by the way, of a young woman's sexual awakening.

After going through this experience with my colleague, I read Robert Pinsky's column in the Washington Post about the poet Hart Crane, whose editor took him to task for some of the details he used in "Melville's Tomb."

At Melville's Tomb

by Hart Crane

Often beneath the wave, wide from this ledge

The dice of drowned men's bones he saw bequeath

An embassy. Their numbers as he watched,

Beat on the dusty shore and were obscured.

And wrecks passed without sound of bells,

The calyx of death's bounty giving back

A scattered chapter, livid hieroglyph,

The portent wound in corridors of shells.

Then in the circuit calm of one vast coil,

Its lashings charmed and malice reconciled,

Frosted eyes there were that lifted altars;

And silent answers crept across the stars.

Compass, quadrant and sextant contrive

No farther tides . . . High in the azure steeps

Monody shall not wake the mariner.

This fabulous shadow only the sea keeps.

Of Crane's poem, Pinsky says, "[It] is lucid in its overall sweep, and that lucidity of the whole depends upon dramatic mystery of texture and detail. In Crane's somberly ornamented tribute to his predecessor, Melville, human instruments of perception are effective but doomed by their limitations. The lifted eyes of religion, the sextant of navigation, Melville's genius: All are ways toward knowledge that contrive or discover meanings, despite their mortal limitations. In a word, they are tragic."

Crane's editor, though, (another Tersteeg?) didn't understand how a portent could possibly be wound in a shell, and so on. Pinsky writes, "Anyone who has ever tried to explain a joke, or a piece of music, or a passion, can sympathize with Crane's exasperated effort to illuminate the essential shadows. Most things people say have denotative as well as connotative meanings. Just as poems often involve quite strict, straightforward logic, even a purchase order may use one term rather than another just because it feels right."

Amen.

My colleague was ready to take her former professor's advice, she said, because she had placed him upon a pedestal. She is now coming to realize, I hope, that for her to elevate him this way is unrealistic, perhaps even dangerous to her art.

Of course, Crane didn't listen to his editor and change his poem. He knew what felt right. But people who are just beginning to explore a certain kind of writing are vulnerable to "advice." You have to be very careful about giving artists advice, because you can never know what beautiful, dramatic, tragic, unique thing you might be killing.

There are all sorts of tombs. There are the ones people's bodies are buried in, but there are also the tombs that our passions and our greatest ideas are buried in. We bury them ourselves, of course, but it's the Tersteegs who helped kill them in the first place. We can't let the Tersteegs define our art; they're not the boss of us. They don't know everything.

There's a threshold that no teacher or mentor can cross. Only the writer knows where she or he has to go. Neither the Tersteegs nor the Beatrices of the world can go there for us or tell us how to get across that threshold, either.

Friday, September 22, 2006

Meant for Now

--Elizabeth Andrew, in an essay entitled “Praying in Place”

Monday, September 18, 2006

Go Into a Wilderness

Where there's nor I nor Thou.

Where is my final goal

towards which I needs must press?

Where there is nothing.

Whither shall I journey now?

Still farther on than God

—into a Wilderness.

--Angelus Silesius

Sunday, September 17, 2006

We act just like the flower does in blooming

Dear people, let the flower in the meadow show you how to please God and be beautiful at the same time. --The rose does not ask why. It blooms because it blooms. It pays no attention to itself nor does it wonder if anyone sees it. --Angelus Silesius

Don't ask how or why and don't fret about if it's any good. Don't worry; it is what it is. It's what it is because it's what you're supposed to do. The flower blooms because it blooms. Write because you write. Don't wonder what people will think if they see it.

I write this, listening to "The Prayer Cycle: Movement I-Mercy" by Jonathan Elias.

Saturday, September 16, 2006

Mysticism and Scholarship

This search for integration has led me to a book written at the turn of the century by a mystic and scholar, Rudolf Steiner. In Mystics After Modernism, Steiner discusses Meister Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, Heinrich Suso, Jan Van Ruysbroeck, Nicholas of Cusa, Agrippa of Nettesheim, Paracelsus, Valentin Weigel, Jacob Boehme, Giordano Bruno, and Angelus Silesius.

The foreword, by Christopher Bamford, is enlightening. Bamford discusses how a certain kind of listening can lead us to "become what we know." This knowledge, this becoming, according to Bamford, "is not a little self, but a self that is ultimately one with the universe."

For some, the contemplative seems shut off from the world, yet Steiner says that "What takes place in our inner life is not a mere [private] mental repetition, but a real part of the universal process."

For the mystic, the divine isn't something external to be repeated within; it is "something real in them to be awakened," says Bamford.

Angelus Silesius put it this way: "I know without me God cannot live for a moment; if I were to come to naught, God would have to give up the ghost. ... God cannot make a single worm without me; if I do not preserve it with God, it would fall apart immediately."

Bamford ends with the statement: "In fact, the world is falling apart, and it is up to us to preserve it."

Two things present themselves from this present exploration:

1) Silesius is talking about a kind of reciprocity not unlike Lao Tzu's.

2) My writing life is my vehicle of awakening and my mode of reciprocity. If the world is falling apart, as Bamford suggests, maybe it's through writing that I do my part to preserve it.

Nature is not humane; we should be like nature

I was intrigued by this because I've always felt drawn to self-sacrifice. It's often where I derive meaning for myself. LeGuin does help me to see self-sacrifice in a new light; well, perhaps not new, because I have thought about the nature of sacrifice before and wondered about its dark side. Says LeGuin:

Nature is definitely not humane. And Lao Tzu says we should be like nature. We should not be humane, either, in the sense that we should not sacrifice ourselves for others. Now that's going to be very hard for Christian readers to accept, because they're taught that self-sacrifice is a good thing. Lao Tzu says it's a lousy thing. This is perhaps the most radical thing he says to a Western ear. Don't buy into self-sacrifice. Any more than you would ask somebody to sacrifice themselves for you. There's a sort of reciprocity--that's the only way I can understand it.

I've been thinking about this since Mother Teresa's recent death. I have never been comfortable with her or with any extreme altruism. It makes me feel inferior, like I ought to be like that, but I'm not. And if I tried to be, it would be the most horrible hypocrisy. But why, what is it that I'm uncomfortable with? And I think maybe Lao Tzu gives me a little handle on that. In a sense, this kind of self-sacrifice occurs only in a society that is so sick that only somebody going too far can make up for the cruelty of the society.

This is startling to me. I've just been reading Karen Armstrong, who goes through each religion and shows how sacrifice became a defining feature. If LeGuin is right, then Lao Tzu's perception of religion is different from the others. It rests on reciprocity, not sacrifice.

Nature is beautiful and sometimes entertaining, but it isn't humane. This, it seems to me, is a truth that's become lost to us. Because we don't live with nature anymore, we've forgotten it's not a place of sacrifice, forgiveness, or grace. The recent deaths of Timothy Treadwell (Grizzly Man) and Steve Irwin (Crocodile Man) illustrate this. Both men have been criticized and blamed for their own deaths. Each man loved nature and sought to preserve it, but in also making it a form of sport and entertainment, they forgot reciprocity. Animals ought to be respected according to their natures, not turned into playthings or teddy bears. Both men forgot how we're connected to things. I believe we all suffer from the same blindness.

I recall an experience I had with the editors of The Sun magazine. They'd accepted a story of mine for publication and the story was going through the editing phase. I can't remember how I'd originally worded the sentence, but it was about give and take, getting something and giving something in return. It was about someone giving a gift on their own birthday, instead of just sitting back and receiving. The editors suggested the word "reciprocity." Looking at the word inserted into my own sentence by the editors, I rather gasped. What a beautiful word. That one word changed a simple idea into something clearly defined, and sacred.

But it isn't until right now, this moment, that I begin to think about what reciprocity means and how this concept might guide my life and my writing.

What if I didn't think of writing as an obligation or as a sacrifice I make by locking myself in a silent room for many hours. What if it is an act of reciprocity? Of giving back, of attempting to reveal some vision or insight I have been given?

Spirit Matters

The writer's imagination must be roomy and supple enough for hope and joy as well as gloom and doom.

Our imaginations must be on call at all times, open to any possibility. So we fight sloth and fear and struggle to show up each day, before the blank page. If a writer can be said to have a spiritual practice, this is it: to stay awake until the imagination stirs and characters come alive in our hands. My hope is that by writing well I will help keep you, the reader, awake--and in love with the human project despite the dark times in which we live.

Buffy, Pinsky, Gluck, and me

I stayed home, cooked something, ate, fiddled around on the Internet, downloaded some Buffy Sainte Marie songs ("Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee," "Starwalker," "Cod'ine," "He's a Keeper of the Fire," "God Is Alive, Magic Is Afoot," "Summer Boy," "Little Wheel, Spin and Spin," "Goodnight.") A dial up connection--hello?--it took a long time.

If you're a woman looking for strength, I highly recommend "Starwalker." It'll make you want to paint your naked body and dance and dare anybody to mess with you. From Buffy's website:

This is one of my [Buffy's] favourite songs, not only because it's a gas to sing it, but also because it's about the incredible energy of our contemporary Indian people. Because of what our ancestors went through for us. I sing it for all our generations past, and all our generations yet to come.

Starwalker he’s a friend of mine

You’ve seen him looking fine he’s a

straight talker

he’s a Starwalker don't drink no wine

ay way hey o heya

Wolf Rider she’s a friend of yours

You’ve seen her opening doors

She’s a history turner

she’s a sweetgrass burner and a

dog soldier

ay hey way hey way heya

Holy light guard the night

Pray up your medicine song oh

straight dealer you’re a spirit healer

keep going on

ay hey way hey way heya

Lightning Woman Thunderchild

Star soldiers one and all oh

Sisters, Brothers all together

Aim straight Stand tall

Starwalker he’s a friend of mine

You’ve seen him looking fine he’s a

straight talker

He’s a Starwalker don't drink no wine

ay way hey o hey...

You have to hear it. The chanting is amazing.

Later, I watched a movie about Edvard Munch. Then I slept until late, fed the cats, watered cats and flowers and pepper plants and tomatoes, checked the mail. Back on the cement slab outside our back door, I heard a strange sound, an animal. It was the rooster, calling to the hens. They were separated from each other and seeking each other out.

I came inside and turned on the Internet. I found this article by Robert Pinsky on Bloglines and the article drew me in and in until I found myself needing to write about it.

Pinsky writes about myths and allusions, how they do their work even if we don't fully understand the implications behind them. He uses a poem by Louise Gluck as illustration.

It's quite something to go from Buffy Sainte Marie lifting her voice in a collective warrior's cry to Gluck's quiet and deep exploration of women's lives. The Persephone Myth is spun into new cloth as the woman first imagines she was abducted by life, then that she offered herself. Two very different paths. Shouldn't each path yield a different arrival? Gluck writes of the "horrible mantle of daughterliness clinging to her." How intriguing. We usually think of Demeter's love for her daughter, of joyful reunion in Spring, not of a burden of belonging. So what is this horrible mantle? I understand it, but with my heart and not my head; I understand with a mystical kind of knowing. The power of myth.

Gluck takes us through the cycle of marriage: Death, husband, God, Stranger. The woman looks into the water, hoping for something about herself to be revealed. What? Who am I? Daughter, wife, mother, self--which? all?

"I am never alone," the woman has thought, then turned the thought into prayer. She sought to escape her body, to merge into someone else's. She's belonged to others, never herself. She wants to be alone, yet is lonely.

Well, time to make a little supper. I miss Allen and Buddha. I miss their physical energy, their play, Allen's laughter. I feel lonely, like the woman at the pool. Later, I'll cradle a book or do some writing, grade some papers. They will be home Sunday, and I will have gotten a lot done, I hope.

---------------------------------

Poet's Choice

By Robert Pinsky

Sunday, September 17, 2006; BW12

A really good allusion works even if you can't identify it. Like myths, allusions change with each repetition. The chariot of the sun, the bitter withy, Tippecanoe and Tyler too, Pandora's box, the Manassas Mauler: They mean more after you have looked them up, but they contain enough hints of sound and image to succeed on their own. Anybody can make a good guess, for example, at which of these phrases are political, mythological or biblical.

Sometimes, the wrong guess is a revealing part of making sense: If a great prizefighter's nickname sounds a little classical or biblical, alluding to him that way becomes part of his meaning. The sound and aroma of the syllables affects the myth.

Without some skill at guessing, who could navigate through any ordinary day with its words and images? Sometimes sorting and guessing is part of the point. The myths and allusions and meanings may be several. They may be invented, merging or overlapping. Here is "A Myth of Innocence," from Louise Glück's recent book Averno :

One summer she goes into the field as usual

stopping for a bit at the pool where she often

looks at herself, to see

if she detects any changes. She sees

the same person, the horrible mantle

of daughterliness still clinging to her.

The sun seems, in the water, very close.

That's my uncle spying again, she thinks--

everything in nature is in some way her relative.

I am never alone, she thinks,

turning the thought into a prayer.

Then death appears, like the answer to a prayer.

No one understands anymore

how beautiful he was. But Persephone remembers.

Also that he embraced her, right there,

with her uncle watching. She remembers

sunlight flashing on his bare arms.

This is the last moment she remembers clearly.

Then the dark god bore her away.

She also remembers, less clearly,

the chilling insight that from this moment

she couldn't live without him again.

The girl who disappears from the pool

will never return. A woman will return,

looking for the girl she was.

She stands by the pool saying, from time to time,

I was abducted, but it sounds

wrong to her, nothing like what she felt.

Then she says, I was not abducted.

Then she says, I offered myself, I wanted

to escape my body. Even, sometimes,

I willed this. But ignorance

cannot will knowledge. Ignorance

wills something imagined, which it believes exists.

All the different nouns--

she says them in rotation.

Death, husband, god, stranger.

Everything sounds so simple, so conversational.

I must have been, she thinks, a simple girl.

She can't remember herself as that person

but she keeps thinking the pool will remember

and explain to her the meaning of her prayer

so she can understand

whether it was answered or not.

The pleasure is partly in the playful distance between writer and character. "Allude" shares its root with "ludic" and "ludicrous," the vocabulary of play. The alternate things the character says, the "different nouns" she tries, the trickiness of a word such as "simple": These illustrate the shimmery nature of meaning, which inspires the devisings of myth, as well as the pranks of allusion.

(Louise Glück's poem "A Myth of Innocence" is from her book "Averno." Farrar Straus Giroux. Copyright © 2006 by Louise Glück.)

Friday, September 15, 2006

Invocation

Mother of all that is written

Inspire fluent, truthful words.

May I discover the sacred river of wisdom within.

-- Invocation of Saraswati, the Hindu Goddess of Inspiration

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Books are alive

She said, "You teach literature, don't you?" I said I did, and she asked if I liked doing that. I said I did like it very much, that literature teaches us the meaning of the world. She smiled radiantly and said, "It teaches us the meaning of LIFE."

We who love literature know its power to teach and to change. You can still give this gift to yourself. Remember how you loved to read and write when you were young, and embrace it all again in newness and wonder. It's still good. Books are alive.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Expanding the reach of who you are

People say art is a substitute religion, and I thought about a lot about that in the aftermath of 9/11. It's true that art transports you, that it gives you the sense that you can find other worlds than the ones that you know are inside of you. There are so many imagined worlds. Each artist creates a world with its own logic and its own set of rules in which you can move in and inhabit. They find form that lets you imaginatively take part in experiences with which you may not have had any contact, and for a moment, conceive of a world as pearlescent and as beautifully, rectilinearly ordered as a Piero. To feel these things through art expands the reach of who you are.

But art doesn't only transport you to new, imagined places. It also, in the best sense, narrows your vision, focuses with a new immediacy on the things that may be the most familiar to you. It gives a new spiritual dimension to the objects that you touch, to the room that you inhabit. And this is not just a tidy or comfortable experience but can be suffused with a kind Dionysian pleasure, in the sense of the small world controlled and the poetry of the world possessed, this crossing over of the line between what is the love of the material thing, of the dust mote in the sunlight or the sheen of the porcelain, of the look of the ivy winding around the bowl of fish, you know, this sort of pleasure in the daily small things. In art, through art, I think, transmutes itself into a form of spirituality, one to which I respond very, very strongly. --KIRK VARNEDOE, former directer of MoMA

I believe this transport was also experienced by van Gogh. In his letters he speaks so much about the power of color to transport him; he had a special affinity for yellow. Van Gogh's experience with art is particularly intriguing, since he once wanted to go into the ministry. Can it be that art became his religion?

The poets Dickey, Roethke, and James Wright spoke of poetry transporting them. Dickey described being on a city street with Wright and Robert Bly and sinking to his knees in awe of poetry. I've read many of James Wright's letters, in which he speaks of reading, or writing, a poem and of transcending the ordinary. James Agee, who also wrote poetry, but who is mostly known for his prose works, like Death in the Family, also wrote of how his struggle with art led him to ephiphany.

In my own case, I feel a sense of rightness and connectedness when the writing is going well. It's as though the neurons in my brain are firing in just the right pattern, allowing me to experience many things at once, and through this explosive integration, I'm able to see the "truth." (In a recent Sun article, the author says scientists have actually observed this phenomenon in the brain.) Joseph Campbell called this a "peak" moment, and he connected it with the transcendent. When I reach this point while writing, it feels similar to moments I used to have in church back in the late 1970s when I felt a sudden rush of love.

I have to think about whether I agree that art is a "substitute" religion. Vernedoe doesn't say whether or not he agrees, but he does say that we can experience a form of spirituality through art. I do really like what Varnedoe says about what art does, that it expands the imagination and at the same time it narrows your vision. It gives you a chance to focus on very specific things so that you can see how sacred they are. At the same time, it opens you to mystery. Yes, I really like that explanation.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

Yes and No

I've been keeping a separate rather secret blog here at blogspot for a few weeks that I call "Meditations." It's a storehouse of observations and quotes pertaining to my current reading and thinking. It's not enabled for comments and I've not said anything about it because I doubt profoundly that anyone would be interested in it. There's no continuity to it and no commentary. But it does provide me with a place to hopefully find a way of threading together various ideas. I also keep a hard copy of "Meditations" in a little black notebook.

One idea I've been exploring for a long time is writing as a sacred act and as a way of knowing the deepest aspects of ourselves. I began "Meditations" this summer after doing a lot of reading on Theodore Roethke. I've also been picking through letters recently of van Gogh and Edvard Munch. Much earlier, I'd read the letters of Dickey, James Wright, and James Agee.

I went to "Meditations" tonight and reread what van Gogh said about the eternal yes and the eternal no.

Vincent van Gogh writes to Theo of Tersteeg, an art dealer with whom he'd had several unpleasant encounters. Vincent tells what he believes Tersteeg thinks of him and of what Tersteeg has come to represent to Vincent:

[Tersteeg thinks to himself] "You are a mediocrity and you are arrogant because you don't give in and you make mediocre little things: you are making yourself ridiculous with your so-called seeking, and you do not work."

Vincent goes on to say, That is the real meaning of what Tersteeg said to me the year before last, and last year; and he still means it.

I am afraid Tersteeg will always be for me "the everlasting no."

That is what not only I, but almost everyone who seeks his own way, has behind or beside him as an everlasting discourager. Sometimes one is depressed by it and feels miserable and almost stunned.

It's what Vincent says next that makes me think about Allen:

But I repeat, it is the everlasting no; in the cases of men of character, on the contrary, one finds an everlasting yes, and discovers in them "la foi du charbonnier."

For me Allen has been the everlasting yes. He has supported my writing completely, with a believer's faith, since the start. "La foi du charbonnier" means believing in something with a kind of religious acceptance, believing without "thinking" too much.

There have also been many Tersteegs in my life, and sometimes even now when I go about my "seeking," I can hear them deriding me or laughing at me. This is why it's so important to have someone who believes in you. It's so much easier, then, to fend off thoughts of the Tersteegs.

I write this not so much to call attention to my relationship with Allen and not to be depressing with all this talk about death, but to say that we all need that person in whom we find "La foi du charbonnier." I think for Vincent, it was Theo. For me it is Allen.

Friday, September 08, 2006

Didn't You Want to Be a Writer?

If you are like most people (me), before you know it, you will agree wholeheartedly with your naysayers. "What was I thinking?" you will say to yourself every time the urge to write surfaces like an unruly weed, which you and everyone else keep trying to beat to death. "What could I possibly have to say that hasn't already been said by people a thousand times smarter than I will ever be?" Psychologists refer to this as the Stockholm Syndrome -- when captives begin to share the views of their captors. You will so fully internalize their message and adopt it as your own that you will eventually forget it wasn't your opinion to begin with.

You will now enter a long (seemingly placid but emotionally turbulent) period of denial that can sometimes last years (or decades). You will lie. "Who me? Be a writer? And put up with all that rejection? Are you kidding?" You will obfuscate. "Who would want to be a writer? Can you imagine being someone who wanted to be a writer?" When pressed, you will even philosophize: "If a writer writes something that never gets published and is thus never read, is a writer still a writer?"

In order to convince yourself and others that you have "moved on" (accepted defeat without even trying), you will learn to hide in plain sight: You will get a normal job, one with an actual office and an actual desk (engaging in "freelance work" from your apartment or working "odd jobs" with "odd hours" are dead giveaways of your true intentions and unconscious desires). In exchange for your 40 (or 50 or 60) hours a week of work (indentured servitude), you'll receive a respectable paycheck (let's be frank: not much more than you made waitressing in high school at the International House of Pancakes or working the drive-thru at Burger King) and medical benefits (to pay for psychotherapy, twice a week, to deal with the stress of all your repression). Most important, your job will provide you with some financial security and emotional stability (not to mention the perfect opportunity for people watching, eavesdropping, Internet research and working on something -- Fiction? Nonfiction? Comedy? Tragedy? -- even if you don't yet know what that something is).

In addition to the macro-lie (yourself as Career Drone), you'll see that you need to make up lots of little lies to protect your true identity (Secret Writer Person). You'll have to appear ambitious and deserving of promotions (show up before noon); pretend to embrace any and all career-enhancing business trips and client interactions (even though you see any time away from your true calling as a soul-deadening, blood-sucking diversion); and continue to dress the part (never complaining about how dumb it is that you have to spend all your money on work clothes when you could be home writing your novel in your pajamas).

And then one day, out of the blue, just when you think you're finally lost in the jungle, you will see it. You will look at all the papers and files and meaningless detritus on your desk, you will watch all your wonderfully idiosyncratic co-workers racing busily around the office, talking of Michelangelo, and you will stop whatever it is you are doing. The world you've tried so hard to join will suddenly cease to exist, and you will finally see that life without your dream is a wasteland; that you must at least try to do the thing you really want to do even if, in the end, you do not succeed at it. You will be tempted to put the better-to-have-loved-and-lost rule in parentheses, like everything else in your life that you've sidelined and tried to ignore up until now, but you will resist and settle for multiple hyphens instead. It is a step. You are about to head into the great unknown, and you will be tempted to throw away the map to your lost world in triumph, but don't -- you will need something to write on . --Laura Zigman

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

The world is waiting...

Earth, what it has in it!

The past is in it;

All words, feelings, movements,

words, bodies, clothes, girls, trees,

stones, things of beauty, books, desires are in it;

and all are to be known;

Afternoons have to do with the whole world;

And the beauty of mind,

feeling knowingly the world!

Eli Siegel

Making One of Opposites

Sanctuary

One of the most truly beautiful words in the English language, to me, is "sanctuary." I ran across a quote recently from artist Philip Guston:

"As a boy I would hide in the closet when the older brothers and sisters came with their families to mama's apartment for the Sunday afternoon dinner visit. I felt safe. Hearing their talk about illnesses, marriages, and the problems of making a living, I felt my remoteness in the closet with the single light bulb. I read and drew in this private box. Some Sundays I even painted. I had given my dear Mama passionate instructions to lie.... 'Where is Philip?' I could hear them.... 'Oh, he is away, with friends'....I was happy in my sanctuary. After a lifetime, I still have never been able to escape....It is still a struggle to be hidden and feel strange--my favorite mood."

I strongly relate to what Guston said. I never shut myself in a closet, except once when a girlfriend and I hid in my closet and practiced kissing by using the backs of our hands; but as a child I used to shut myself in my room for hours, and when my mother had company I could hear them saying, "Where's Theresa?" My mother made excuses for me, like Guston's did for him. She'd tell them I was reading or doing important school work. I loved peeling myself away from human contact in this way and having time to think, to draw pictures, to paint, to read, to dawdle.

I still do this. I love how Guston says his favorite mood is feeling "strange." I never thought of feeling strange as being a mood, but I guess it is. I also like the feeling of being strange, or apart.

I like the feeling of being alone, of having a sanctuary against the outside world.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

Laughing and Survival

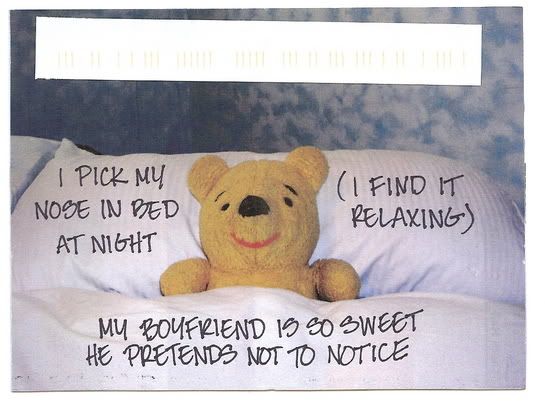

A postcard sent to me for my postcard confessional project. This one is from California.

I haven't had much to laugh about lately, smile maybe, but not laugh. I won't go into detail, but we all know how it goes sometimes. I haven't posted in several days, nor have I visited other blogs, nor have I responded to e-mails. But I am okay. Not on top of the world okay, but surviving okay.

That's why I was delighted today to see this postcard. I taught until 7:30 tonight and when Allen picked me up at the college, the postcard was lying on that hump in the floor between the driver and passenger side. As soon as I read it, my heart just melted, and I laughed and laughed. It's been a while since I've received a confessional postcard, and this one sure came to me at a great time. I'd just spoken with my Women's Studies students this afternoon about "Venerated Madonnas," one way women are still sometimes defined today. I thought to myself, "No Venerated Madonna here! This woman has a fully functional body and delights in it."

Thank you for this postcard, whoever you are.

I have many ideas for stories I want to write, but at the very least I must get past these first few weeks of classes. I do continue to add to my notebooks and am doing targeted reading which helps to keep me connected to my projects.

Thursday, August 10, 2006

Moving to a New House

I snapped these photos today. I just couldn't resist. The lease ran out on our son's apartment and he doesn't move into his new place for three more days. So we brought his stuff here. The top photo shows what it all looked like as soon as Allen pulled up into the yard with our son's things. The bottom photo shows what happened about five minutes later. It sure doesn't take a cat long to find an open drawer.

The photo got me thinking about how many places I lived:

1-When I was born, six of us lived in a tiny eight wide trailer out in the desert of Southern California. I don't remember living here.

2-Next I lived in a ten wide trailer in NC. There were six of us, until my grandmother died when I was nine. I used to sleep with her, which was fun. I used to keep her awake asking all sorts of questions.

3-Then we moved into a brick house just across the street from where our trailer had been.

4-For a short time I lived with my elder brother. My mother and I moved in with him after my mother left my father. She went back to him and we lived in the brick house again.

5-When I got married, I lived in a one bedroom apartment in downtown Jacksonville, NC, right across from a shopping center.

6-Allen and I bought a cheap trailer and lived in this for many years.

7-I stayed in a small eight wide trailer with the children during the week while I took classes at East Carolina University.

8-Allen and I rented a brick house close to the University when I was working on my Master's in English.

9-Allen and I, plus our three sons moved into a two bedroom apartment in Bowling Green so I could get the MFA Degree.

10-We moved into a duplex apartment, a great old house with stained glass windows. We lived there 10 years!

11-Our present home, a 100 year old farmhouse.

I read somewhere that a house is often symbolic of the human body in fiction. I've never thought of moving days the same way since. How many places have you lived?

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

To the Lighthouse

Marblehead Lighthouse on Lake Erie.

Why create? Virginia Woolf answers this in her novel, To The Lighthouse. We create because we have to, because it keeps us sane, because it's a way to feel what it means to be alive. This is what Woolf says at the end of her novel. The character is just finishing a painting:

Quickly...she turned to her canvas. there it was--her picture. Yes, with all its greens and blues. its lines running up and across, its attempt at something. It would be hung in attics, she thought; it would be destroyed. But what did that matter? she asked herself, taking up her brush again. She looked at the steps; they were empty; she looked at her canvas; it was blurred. With sudden intensity, as if she saw it clear for a second, she drew a line there, in the centre. It was done; it was finished. Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue. I have had my vision.

Generations

Photo: Durga gives her grandmother the stolen guava.