Tonight I watched Faith and Doubt at Ground Zero on PBS for the second time. The first time I saw it was several months ago. It's a powerful exploration of how people's belief in God changed after 9/11. Kirk Varnedoe, the former director of the Museum of Modern Art, had the following to say about art and religion:

People say art is a substitute religion, and I thought about a lot about that in the aftermath of 9/11. It's true that art transports you, that it gives you the sense that you can find other worlds than the ones that you know are inside of you. There are so many imagined worlds. Each artist creates a world with its own logic and its own set of rules in which you can move in and inhabit. They find form that lets you imaginatively take part in experiences with which you may not have had any contact, and for a moment, conceive of a world as pearlescent and as beautifully, rectilinearly ordered as a Piero. To feel these things through art expands the reach of who you are.

But art doesn't only transport you to new, imagined places. It also, in the best sense, narrows your vision, focuses with a new immediacy on the things that may be the most familiar to you. It gives a new spiritual dimension to the objects that you touch, to the room that you inhabit. And this is not just a tidy or comfortable experience but can be suffused with a kind Dionysian pleasure, in the sense of the small world controlled and the poetry of the world possessed, this crossing over of the line between what is the love of the material thing, of the dust mote in the sunlight or the sheen of the porcelain, of the look of the ivy winding around the bowl of fish, you know, this sort of pleasure in the daily small things. In art, through art, I think, transmutes itself into a form of spirituality, one to which I respond very, very strongly. --KIRK VARNEDOE, former directer of MoMA

I believe this transport was also experienced by van Gogh. In his letters he speaks so much about the power of color to transport him; he had a special affinity for yellow. Van Gogh's experience with art is particularly intriguing, since he once wanted to go into the ministry. Can it be that art became his religion?

The poets Dickey, Roethke, and James Wright spoke of poetry transporting them. Dickey described being on a city street with Wright and Robert Bly and sinking to his knees in awe of poetry. I've read many of James Wright's letters, in which he speaks of reading, or writing, a poem and of transcending the ordinary. James Agee, who also wrote poetry, but who is mostly known for his prose works, like Death in the Family, also wrote of how his struggle with art led him to ephiphany.

In my own case, I feel a sense of rightness and connectedness when the writing is going well. It's as though the neurons in my brain are firing in just the right pattern, allowing me to experience many things at once, and through this explosive integration, I'm able to see the "truth." (In a recent Sun article, the author says scientists have actually observed this phenomenon in the brain.) Joseph Campbell called this a "peak" moment, and he connected it with the transcendent. When I reach this point while writing, it feels similar to moments I used to have in church back in the late 1970s when I felt a sudden rush of love.

I have to think about whether I agree that art is a "substitute" religion. Vernedoe doesn't say whether or not he agrees, but he does say that we can experience a form of spirituality through art. I do really like what Varnedoe says about what art does, that it expands the imagination and at the same time it narrows your vision. It gives you a chance to focus on very specific things so that you can see how sacred they are. At the same time, it opens you to mystery. Yes, I really like that explanation.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Pages

Dreaming

About Me

- Theresa Williams

- Northwest Ohio, United States

- "I was no better than dust, yet you cannot replace me. . . Take the soft dust in your hand--does it stir: does it sing? Has it lips and a heart? Does it open its eyes to the sun? Does it run, does it dream, does it burn with a secret, or tremble In terror of death? Or ache with tremendous decisions?. . ." --Conrad Aiken

Followers

Facebook Badge

Search This Blog

Favorite Lines

My Website

Epistle, by Archibald MacLeish

Visit my Channel at YouTube

Great Artists

www.flickr.com

This is a Flickr badge showing public photos from theresarrt7. Make your own badge here.

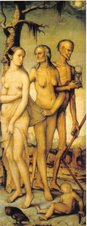

Fave Painting: Eden

Fave Painting: The Three Ages of Man and Death

by Albrecht Dürer

From the First Chapter

The Secret of Hurricanes : That article in the Waterville Scout said it was Shake- spearean, all that fatalism that guides the Kennedys' lives. The likelihood of untimely death. Recently, another one died in his prime, John-John in an airplane. Not long before that, Bobby's boy. While playing football at high speeds on snow skis. Those Kennedys take some crazy chances. I prefer my own easy ways. Which isn't to say my life hasn't been Shake-spearean. By the time I was sixteen, my life was like the darkened stage at the end of Hamlet or Macbeth. All littered with corpses and treachery.

My Original Artwork: Triptych

Wishing

Little Deer

Transformation

Looking Forward, Looking Back

Blog Archive

-

▼

2006

(96)

-

▼

September

(20)

- Apocalyptic Thinking

- When Nations grow Old...

- The Permanent Realities of Every Thing

- Tombs

- Meant for Now

- Go Into a Wilderness

- We act just like the flower does in blooming

- Mysticism and Scholarship

- Nature is not humane; we should be like nature

- Spirit Matters

- Buffy, Pinsky, Gluck, and me

- Invocation

- Books are alive

- Expanding the reach of who you are

- "Into all abysses I still carry the blessings of m...

- Yes and No

- Didn't You Want to Be a Writer?

- The world is waiting...

- Making One of Opposites

- Sanctuary

-

▼

September

(20)

CURRENT MOON

Labels

- adolescence (1)

- Airstream (7)

- Alain de Botton (1)

- all nighters (2)

- Allen (1)

- altars (1)

- Angelus Silesius (2)

- animals (1)

- Annie Dillard (1)

- Antonio Machado (2)

- AOL Redux (1)

- April Fool (1)

- Archibald MacLeish (1)

- arts and crafts (55)

- Auden (1)

- awards (2)

- AWP (2)

- Bach (1)

- Basho (5)

- Beauty and the Beast (1)

- birthdays (1)

- blogs (5)

- boats (2)

- body (2)

- books (7)

- bookstores (1)

- Buddha (1)

- Buddha's Little Instruction Book (2)

- butterfly (4)

- buzzard (2)

- Capote (4)

- Carmel (1)

- Carson McCullers (1)

- cats (15)

- Charles Bukowski (1)

- Charles Simic (2)

- Christina Georgina Rossetti (1)

- church (2)

- confession (1)

- Conrad Aiken (1)

- cooking (5)

- crows (1)

- current events (2)

- D. H. Lawrence (3)

- death (6)

- Delmore Schwartz (4)

- detachment (1)

- dogs (7)

- domestic (3)

- dreams (21)

- Edward Munch (4)

- Edward Thomas (1)

- Eliot (3)

- Eliot's Waste Land (2)

- Emerson (2)

- Emily Dickinson (10)

- ephemera (1)

- Esalen (6)

- essay (3)

- Eugene O'Neill (3)

- Ezra Pound (1)

- F. Scott Fitzgerald (1)

- fairy tales (7)

- Fall (16)

- Famous Quotes (16)

- festivals (2)

- fire (5)

- Floreta (1)

- food (1)

- found notes etc. (1)

- found poem (2)

- fragments (86)

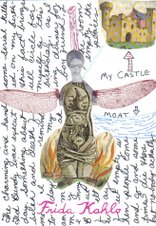

- Frida Kahlo (1)

- frogs-toads (4)

- Georg Trakl (1)

- gifts (1)

- Global Warming (1)

- Gluck (1)

- goats (1)

- Goodwill (1)

- Great lines of poetry (2)

- Haibun (15)

- haibun moleskine journal 2010 (2)

- Haiku (390)

- Hamlet (1)

- Hart Crane (4)

- Hayden Carruth (1)

- Henry Miller (1)

- holiday (12)

- Hyman Sobiloff (1)

- Icarus (1)

- ikkyu (5)

- Imagination (7)

- Ingmar Bergman (1)

- insect (2)

- inspiration (1)

- Issa (5)

- iTunes (1)

- Jack Kerouac (1)

- James Agee (2)

- James Dickey (5)

- James Wright (6)

- John Berryman (3)

- Joseph Campbell Meditation (2)

- journaling (1)

- Jung (1)

- Juniper Tree (1)

- Kafka (1)

- Lao Tzu (1)

- letters (1)

- light (1)

- Lorca (1)

- Lorine Niedecker (2)

- love (3)

- Lucille Clifton (1)

- Marco Polo Quarterly (1)

- Marianne Moore (1)

- Modern Poetry (14)

- moon (6)

- movies (20)

- Muriel Stuart (1)

- muse (3)

- music (8)

- Mystic (1)

- mythology (6)

- nature (3)

- New Yorker (2)

- Nietzsche (1)

- Northfork (2)

- November 12 (1)

- October (6)

- original artwork (21)

- original poem (53)

- Our Dog Buddha (6)

- Our Dog Sweet Pea (7)

- Our Yard (6)

- PAD 2009 (29)

- pad 2010 (30)

- Persephone (1)

- personal story (1)

- philosophy (1)

- Phoku (2)

- photographs (15)

- Picasso (2)

- Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1)

- Pillow Book (5)

- Pinsky (2)

- plays (1)

- poem (11)

- poet-seeker (9)

- poet-seer (6)

- poetry (55)

- politics (1)

- poppies (2)

- presentations (1)

- Provincetown (51)

- Publications (new and forthcoming) (13)

- rain (4)

- Randall Jarrell (1)

- reading (6)

- recipes (1)

- Reciprocity (1)

- Richard Brautigan (3)

- Richard Wilbur (2)

- Rilke (5)

- river (5)

- river novel (1)

- rivers (12)

- Robert Frost (2)

- Robert Rauschenberg (1)

- Robert Sean Leonard (1)

- Robinson Jeffers (1)

- Rollo May (2)

- Rumi (1)

- Ryokan (1)

- Sexton (1)

- short stories (13)

- skeletons (2)

- sleet (1)

- snake (1)

- Snow (24)

- solitude (1)

- spider (2)

- spring (1)

- Stanley Kunitz (1)

- students (2)

- suffering (4)

- suicide (2)

- summer (20)

- Sylvia Plath (2)

- Talking Writing (1)

- Tao (3)

- teaching (32)

- television (4)

- the artist (2)

- The Bridge (3)

- The Letter Project (4)

- The Shining (1)

- Thelma and Louise (1)

- Theodore Roethke (16)

- Thomas Gospel (1)

- Thomas Hardy (1)

- toys (3)

- Transcendentalism (1)

- Trickster (2)

- Trudell (1)

- Ursula LeGuin (1)

- vacation (10)

- Vermont (6)

- Virginia Woolf (1)

- Vonnegut (2)

- Wallace Stevens (1)

- Walt Whitman (8)

- weather (7)

- website (3)

- what I'm reading (2)

- William Blake (2)

- William Butler Yeats (5)

- wind (3)

- wine (2)

- winter (24)

- wood (3)

- Writing (111)

- Zen (1)

6 comments:

I like that explanation as well. Art is just one way of experiencing the sacred which is something that transcends any religion. Religions exist as a road map showing the way that other people have experienced the truly Holy in their lives, but they are only the map. Art can be a map as well, but in the creation or fully conscious experience of art, we can experience the Sacred personally for ourselves. Great entry.

For me, too, there is something transcendent and spiritual about art, and this is true whether I am creating it, or experiencing the art of someone else that speaks to me. There is that sense of awe that is vast and at the same time, condensed as tight as a pencil point, and when the feeling comes, I am inside the awe and surrounded by the awe and at one with the awe. Teagrapple

What an interesting connection between art and religion. I love Varnedoe's description. I especially like his thought on giving a spiritual dimension to the objects you touch. The concept of divine in everyday feels very freeing and very important to me.

Teagrapple, it was interesting that you mentioned art that "speaks to you". I've heard that phrase often, but in the context of this post, it really makes sense! As God has "spoken to" people throughout the ages, I think art also has that power to transcend the senses and speak a language of love and discovery.

Thank you, Erin, that's it, exactly. Teagrapple

“To still keep that openness, that chance taking-ness as part of the work. Not to be afraid to make a mistake, even if it's a long and costly mistake.” - J. Dickey

This is the first I’ve read of your blog, and portions of it speak to an instinct about writing I’ve failed (or been too lazy) to articulate.

Two things you’ve noted about Dickey are things accounted for in the writings of other authors.

1. One of my favorite writers, William T. Vollmann, has spoken at length on the importance of getting over the fear of having others judge your writing; similarly, he’s spoken on the importance of a generalized fearlessness in engaging the subject of his writings -- that is, taming the fear of making mistakes technically, stylistically, and morally. This is echoed by the foregoing Dickey quote, and, taken together, Vollmann and Dickey remind us that Agee, and Hemingway, and Isak Dinesen, and Kerouac remarked on their battles with fear: fear of being judged, and fear of judging oneself.

2. On creative focus and the (inadvertent?) achievement of transcendence -- the act of writing as a kind of powerfully insightful meditative experience -- the following quote, though lengthy, better summarizes my perception of what the experience of the act of writing is better than anything I've read elsewhere, and, not coincidentally, it is excerpted from Dickey’s celebrated eulogy for Truman Capote at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1984.

For any moved by it, and for any curious about the phenomena of the act of writing, it is essential to read the eulogy in full, which resides on page 464 of George Plimpton’s 1997 oral biography of Capote, “Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances, and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career” (ISBN: 0-385-23249-7):

-- to contextualize, the following remarks emerge from Dickey’s comparison of Proust and Capote, and the body of work that Capote might have produced given a lengthier (and more sober) stay on earth --

“… What a death, and what a work of literature might have resulted!

All speculation, indeed, but death brings on and encourages speculation as nothing else can. Could Capote have done something like this? If one surmises that he might have come to attempt it, what would be the factor that caused him to try? The belief in his own talent. Did it exist? It did; indeed it did.

The talent of Truman Capote: that is where we can engage him, all speculation aside. This small childlike individual, this self-styled, self-made, self-taught country boy – what did he teach himself? To concentrate: to close out, and close in: to close with. His writing came, first, from a great and very real interest in many things and people, and then from a peculiar form of detachment that he practiced as one might practice the piano, or a foot position in ballet. Cultivated in this manner, his powers of absorption in a subject became very nearly absolute, and his memory was already remarkable, particularly in its re-creation of small details. He possessed to an unusual degree this ability to encapsulate himself with his subject, whatever or whoever it might be, so that nothing else existed except him and the other; and then he himself would begin to fade away and words would appear in his place: words concerning the subject, as though it were dictating itself. In the best of his work, this self-canceling solipsism, if this be not too self-contradictory an estimate, amounted to Truman’s vision of things, and he could call it into service under any circumstances, and with any person, from Marlon Brando or Isak Dinesen or Bobby Beausoleil in San Quentin or Perry Smith on death row in Kansas. All Truman’s work was a result of this power of isolation-with, of concentration and super-attention. His journalism, including his so-called non-fiction novels, was made possible by means of it, but I prefer to speak of a deeper, more lasting thing than the pursuit of fact allows, and look, if only momentarily, at what came to Truman in the form of words when closed not with Marilyn Monroe or Perry Smith, but with himself and his own life: what words then took place of him?

Words standing for one of the purest and most generally felt conditions of our human time, or of any human time: isolation, loneliness, foresakeness, lostness: the lostness that tends to hallucination, dementia, paranoia: “The notion of some infinitely gentle / Infinitely suffering thing,” but which also, taking as refuge and resource the imagination, call another order of being into play, into existence:

"‘You ever see the snow?’

Rather breathlessly Joel lied and claimed that he most certainly had; it was a pardonable deception, for he had a great yearning to see bona-fide snow; next to owning the Koh-i-noor diamond, that was his ultimate secret wish. Sometimes, on flat boring afternoons, he’s squatted on St. Deval Street and daydreamed silent pearly snowclouds into sifting coldly through the boughs of the dry, dirty trees. Snow falling in August and silvering the glassy pavement, the ghostly flakes icing his hair, coating rooftops, changing the grimy old neighborhood into a hushed frozen white wasteland uninhabited except for himself and a menagerie of wonderbeasts: albino antelopes, and ivory-breasted snowbirds; and occasionally there were humans, such fantastic folk as Mr. Mystery, the vaudeville hypnotist, and Lucky Rogers, the movie star, and Madame Veronica, who read fortunes in a Vieux Carre tearoom. ‘It was one stormy night in Canada that I saw the snow,’ he said, though the farthest north he’d ever set foot was Richmond, Virginia."

I find myself returning often to Other Voice, Other Rooms, but more often to the shorter pieces of The Tree of Night, and I believe I do this because I think of Capote’s gift as essentially lyrical, poetic: the stamp-minted event, the scene stunning with rightness and strangeness, the compressed phrase, the exact yet imaginative word, the devastating metaphorical aptness, a feeling of concentrated excess which at the same time gives the effect of being crystalline. One can say of these stories, like “Miriam” and “Shut a Final Door,” which in other hands would bear too many resemblances to gothic movies, with lots of melodrama, props, grotesque stage businesses, that they are saved by the only quality that can save any writer’s anything: his personal vision, which in Capote’s case runs to unforgettable images of fear, hopelessness, and dream-death: in addition to cold, also its opposite: airlessness, heat, ripe rot, the submerged corpse green in the moveless pool.

It is maybe paradoxical, but not finally so, that such images – many of his best – of the stultified, the still, the overhot and overripe come like the others from Truman Capote’s lenslike detachment, and suggest, rather than lushness and softness, things wrought by the engraver’s delicate hammer, the artist working with otherworldly intensity upon materials from the world, as the universe makes a snowflake, the most fastidiously created of artifacts, resulting in a true work of literature, which, unlike the snowflake, keeps on existing. The sure-handed crystal-making detachment, the integrity of concentration, the craft of the artist by means of which the intently human is caught, Truman Capote had, and not just at certain times but at all times. This we remember, and will keep, for it gave us what of him will stay. Keep him we will, and from such a belief come these few lines, something.

PS: The former response was posted a a new "anonymous," who should have signed off as "nineiron10@gmail.com."

Enjoying you blog. Take care.

Post a Comment