For starters, this link will take you to an overview of Bob Woodward's new book about how the present administration has been in a state of denial about how the war is going in Iraq. Woodward is going to be on 60 Minutes Sunday night; I wouldn't miss it for anything.

Images of war shatter me and move my thinking toward Apocalypse.

I have been asking my composition students to write about the effects of war. I showed them two films, The Grave of the Fireflies and Regret to Inform. Fireflies is an anime tale about the firebombing of Japan during WWII. Regret to Inform is a heartbreaking documentary account of the toll of the Vietnam War on several women, mostly wives, both American and Vietnamese. The stories of the women are threaded together by one American woman's journey to visit the place where her husband, Jeff, died. One of my students, who is a soldier, was very affected by Regret to Inform, saying it has changed everything about his thinking regarding war. After reading his remarks in an in-class writing, I nearly cried.

Papers to grade this weekend and all week long. Papers, papers, papers.

I've been reading so much non-fiction lately that I'm starting to get hungry for fiction again. I just ordered three novels: The Road by Cormac McCarthy, The Echo Maker by Richard Powers, and The Lay of the Land by Richard Ford. I've read McCarthy and Ford before, but not Powers. I especially look forward to The Road. I like McCarthy's dark, Faulknerian view of life and his prose sweeps you away like a rough river. I think all three of these novels may be Apocalyptic in their own way.

Saturday, September 30, 2006

Saturday, September 23, 2006

When Nations grow Old...

"When Nations grow Old, The Arts grow Cold, and Commerce settles on every Tree." --William Blake

The Permanent Realities of Every Thing

He whose face gives no light,

shall never become a star.

In every bosom

a Universe expands as wings.

This world of Imagination

is a World of Eternity:

It is the Divine bosom

into which we shall all go

After the death of the Vegetated body.

This World of Imagination is Infinite and Eternal,

Whereas the world of Generation or Vegetation

Is Finite and Temporal.

There Exists in that Eternal World

The Permanent Realities of Every Thing

Which we see reflected

In this Vegetable Glass of Nature.

by William Blake

shall never become a star.

In every bosom

a Universe expands as wings.

This world of Imagination

is a World of Eternity:

It is the Divine bosom

into which we shall all go

After the death of the Vegetated body.

This World of Imagination is Infinite and Eternal,

Whereas the world of Generation or Vegetation

Is Finite and Temporal.

There Exists in that Eternal World

The Permanent Realities of Every Thing

Which we see reflected

In this Vegetable Glass of Nature.

by William Blake

Tombs

Over the weekend I received an e-mail from a colleague who had recently given me a copy of story she'd been working on so I could give her some comments on it. This colleague got her Master's in Fine Arts (MFA) in Poetry writing and this was her first story attempt.

In the e-mail, my colleage told me not to bother anymore to read and comment on the story, that she'd shared it with a former professor and he'd told her, pretty much, that the story is rubbish and she should stick to poetry.

I hadn't read the story yet, but now I was really curious, so I got it out of my brief case and read it, and I could feel that familiar anger that has to do with the Tersteegs, the "everlasting no." My colleague's professor had given her awful advice, one of those cold, academic responses that make story-telling sound like some kind of specialized skill rather than an innate need.

So now because of the soul-crushing "advice" she'd received, my colleague was ready to give up on story writing all together. I told her I hope she continues to work on her story, that even if it never sees publication, it's still important that she writes it, that she lives with it for a while, that she gives it a chance before she strangles it while it's still in the cradle.

"Sure," I told my colleague. "There are techniques and skills that we acquire along the way, but not knowing those isn't a reason to stop writing stories!"

It's a lovely story, by the way, of a young woman's sexual awakening.

After going through this experience with my colleague, I read Robert Pinsky's column in the Washington Post about the poet Hart Crane, whose editor took him to task for some of the details he used in "Melville's Tomb."

At Melville's Tomb

by Hart Crane

Often beneath the wave, wide from this ledge

The dice of drowned men's bones he saw bequeath

An embassy. Their numbers as he watched,

Beat on the dusty shore and were obscured.

And wrecks passed without sound of bells,

The calyx of death's bounty giving back

A scattered chapter, livid hieroglyph,

The portent wound in corridors of shells.

Then in the circuit calm of one vast coil,

Its lashings charmed and malice reconciled,

Frosted eyes there were that lifted altars;

And silent answers crept across the stars.

Compass, quadrant and sextant contrive

No farther tides . . . High in the azure steeps

Monody shall not wake the mariner.

This fabulous shadow only the sea keeps.

Of Crane's poem, Pinsky says, "[It] is lucid in its overall sweep, and that lucidity of the whole depends upon dramatic mystery of texture and detail. In Crane's somberly ornamented tribute to his predecessor, Melville, human instruments of perception are effective but doomed by their limitations. The lifted eyes of religion, the sextant of navigation, Melville's genius: All are ways toward knowledge that contrive or discover meanings, despite their mortal limitations. In a word, they are tragic."

Crane's editor, though, (another Tersteeg?) didn't understand how a portent could possibly be wound in a shell, and so on. Pinsky writes, "Anyone who has ever tried to explain a joke, or a piece of music, or a passion, can sympathize with Crane's exasperated effort to illuminate the essential shadows. Most things people say have denotative as well as connotative meanings. Just as poems often involve quite strict, straightforward logic, even a purchase order may use one term rather than another just because it feels right."

Amen.

My colleague was ready to take her former professor's advice, she said, because she had placed him upon a pedestal. She is now coming to realize, I hope, that for her to elevate him this way is unrealistic, perhaps even dangerous to her art.

Of course, Crane didn't listen to his editor and change his poem. He knew what felt right. But people who are just beginning to explore a certain kind of writing are vulnerable to "advice." You have to be very careful about giving artists advice, because you can never know what beautiful, dramatic, tragic, unique thing you might be killing.

There are all sorts of tombs. There are the ones people's bodies are buried in, but there are also the tombs that our passions and our greatest ideas are buried in. We bury them ourselves, of course, but it's the Tersteegs who helped kill them in the first place. We can't let the Tersteegs define our art; they're not the boss of us. They don't know everything.

There's a threshold that no teacher or mentor can cross. Only the writer knows where she or he has to go. Neither the Tersteegs nor the Beatrices of the world can go there for us or tell us how to get across that threshold, either.

In the e-mail, my colleage told me not to bother anymore to read and comment on the story, that she'd shared it with a former professor and he'd told her, pretty much, that the story is rubbish and she should stick to poetry.

I hadn't read the story yet, but now I was really curious, so I got it out of my brief case and read it, and I could feel that familiar anger that has to do with the Tersteegs, the "everlasting no." My colleague's professor had given her awful advice, one of those cold, academic responses that make story-telling sound like some kind of specialized skill rather than an innate need.

So now because of the soul-crushing "advice" she'd received, my colleague was ready to give up on story writing all together. I told her I hope she continues to work on her story, that even if it never sees publication, it's still important that she writes it, that she lives with it for a while, that she gives it a chance before she strangles it while it's still in the cradle.

"Sure," I told my colleague. "There are techniques and skills that we acquire along the way, but not knowing those isn't a reason to stop writing stories!"

It's a lovely story, by the way, of a young woman's sexual awakening.

After going through this experience with my colleague, I read Robert Pinsky's column in the Washington Post about the poet Hart Crane, whose editor took him to task for some of the details he used in "Melville's Tomb."

At Melville's Tomb

by Hart Crane

Often beneath the wave, wide from this ledge

The dice of drowned men's bones he saw bequeath

An embassy. Their numbers as he watched,

Beat on the dusty shore and were obscured.

And wrecks passed without sound of bells,

The calyx of death's bounty giving back

A scattered chapter, livid hieroglyph,

The portent wound in corridors of shells.

Then in the circuit calm of one vast coil,

Its lashings charmed and malice reconciled,

Frosted eyes there were that lifted altars;

And silent answers crept across the stars.

Compass, quadrant and sextant contrive

No farther tides . . . High in the azure steeps

Monody shall not wake the mariner.

This fabulous shadow only the sea keeps.

Of Crane's poem, Pinsky says, "[It] is lucid in its overall sweep, and that lucidity of the whole depends upon dramatic mystery of texture and detail. In Crane's somberly ornamented tribute to his predecessor, Melville, human instruments of perception are effective but doomed by their limitations. The lifted eyes of religion, the sextant of navigation, Melville's genius: All are ways toward knowledge that contrive or discover meanings, despite their mortal limitations. In a word, they are tragic."

Crane's editor, though, (another Tersteeg?) didn't understand how a portent could possibly be wound in a shell, and so on. Pinsky writes, "Anyone who has ever tried to explain a joke, or a piece of music, or a passion, can sympathize with Crane's exasperated effort to illuminate the essential shadows. Most things people say have denotative as well as connotative meanings. Just as poems often involve quite strict, straightforward logic, even a purchase order may use one term rather than another just because it feels right."

Amen.

My colleague was ready to take her former professor's advice, she said, because she had placed him upon a pedestal. She is now coming to realize, I hope, that for her to elevate him this way is unrealistic, perhaps even dangerous to her art.

Of course, Crane didn't listen to his editor and change his poem. He knew what felt right. But people who are just beginning to explore a certain kind of writing are vulnerable to "advice." You have to be very careful about giving artists advice, because you can never know what beautiful, dramatic, tragic, unique thing you might be killing.

There are all sorts of tombs. There are the ones people's bodies are buried in, but there are also the tombs that our passions and our greatest ideas are buried in. We bury them ourselves, of course, but it's the Tersteegs who helped kill them in the first place. We can't let the Tersteegs define our art; they're not the boss of us. They don't know everything.

There's a threshold that no teacher or mentor can cross. Only the writer knows where she or he has to go. Neither the Tersteegs nor the Beatrices of the world can go there for us or tell us how to get across that threshold, either.

Friday, September 22, 2006

Meant for Now

Wakefulness isn’t meant for a later date. ... Our creative lives -- the lives we’ve always wanted, full of revelry and rejoicing and the intricate textures of grief, the lives of potential fulfilled, time fattened with intention; they are meant for now.

--Elizabeth Andrew, in an essay entitled “Praying in Place”

--Elizabeth Andrew, in an essay entitled “Praying in Place”

Monday, September 18, 2006

Go Into a Wilderness

Where is my hiding-place?

Where there's nor I nor Thou.

Where is my final goal

towards which I needs must press?

Where there is nothing.

Whither shall I journey now?

Still farther on than God

—into a Wilderness.

--Angelus Silesius

Where there's nor I nor Thou.

Where is my final goal

towards which I needs must press?

Where there is nothing.

Whither shall I journey now?

Still farther on than God

—into a Wilderness.

--Angelus Silesius

Sunday, September 17, 2006

We act just like the flower does in blooming

Or maybe this is what it means to be a writer, to act just like the flower does in blooming:

Dear people, let the flower in the meadow show you how to please God and be beautiful at the same time. --The rose does not ask why. It blooms because it blooms. It pays no attention to itself nor does it wonder if anyone sees it. --Angelus Silesius

Don't ask how or why and don't fret about if it's any good. Don't worry; it is what it is. It's what it is because it's what you're supposed to do. The flower blooms because it blooms. Write because you write. Don't wonder what people will think if they see it.

I write this, listening to "The Prayer Cycle: Movement I-Mercy" by Jonathan Elias.

Dear people, let the flower in the meadow show you how to please God and be beautiful at the same time. --The rose does not ask why. It blooms because it blooms. It pays no attention to itself nor does it wonder if anyone sees it. --Angelus Silesius

Don't ask how or why and don't fret about if it's any good. Don't worry; it is what it is. It's what it is because it's what you're supposed to do. The flower blooms because it blooms. Write because you write. Don't wonder what people will think if they see it.

I write this, listening to "The Prayer Cycle: Movement I-Mercy" by Jonathan Elias.

Saturday, September 16, 2006

Mysticism and Scholarship

Part of my task as a writer has been to integrate my inclination toward the sacred, toward mysticism, with my scholarly pursuits. I've always felt a little off kilter in academic environments which are more than a little left-brained and practical. It leaves me feeling a bit like a "flake," sometimes, and I don't like feeling that way. Like the novelist Edith Wharton, who was born the same day of the month that I was, I've always had the need to be taken seriously by my peers and especially my colleagues at the university. My reputation, my very future at the university, is dependant on their respect for what I do.

This search for integration has led me to a book written at the turn of the century by a mystic and scholar, Rudolf Steiner. In Mystics After Modernism, Steiner discusses Meister Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, Heinrich Suso, Jan Van Ruysbroeck, Nicholas of Cusa, Agrippa of Nettesheim, Paracelsus, Valentin Weigel, Jacob Boehme, Giordano Bruno, and Angelus Silesius.

The foreword, by Christopher Bamford, is enlightening. Bamford discusses how a certain kind of listening can lead us to "become what we know." This knowledge, this becoming, according to Bamford, "is not a little self, but a self that is ultimately one with the universe."

For some, the contemplative seems shut off from the world, yet Steiner says that "What takes place in our inner life is not a mere [private] mental repetition, but a real part of the universal process."

For the mystic, the divine isn't something external to be repeated within; it is "something real in them to be awakened," says Bamford.

Angelus Silesius put it this way: "I know without me God cannot live for a moment; if I were to come to naught, God would have to give up the ghost. ... God cannot make a single worm without me; if I do not preserve it with God, it would fall apart immediately."

Bamford ends with the statement: "In fact, the world is falling apart, and it is up to us to preserve it."

Two things present themselves from this present exploration:

1) Silesius is talking about a kind of reciprocity not unlike Lao Tzu's.

2) My writing life is my vehicle of awakening and my mode of reciprocity. If the world is falling apart, as Bamford suggests, maybe it's through writing that I do my part to preserve it.

This search for integration has led me to a book written at the turn of the century by a mystic and scholar, Rudolf Steiner. In Mystics After Modernism, Steiner discusses Meister Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, Heinrich Suso, Jan Van Ruysbroeck, Nicholas of Cusa, Agrippa of Nettesheim, Paracelsus, Valentin Weigel, Jacob Boehme, Giordano Bruno, and Angelus Silesius.

The foreword, by Christopher Bamford, is enlightening. Bamford discusses how a certain kind of listening can lead us to "become what we know." This knowledge, this becoming, according to Bamford, "is not a little self, but a self that is ultimately one with the universe."

For some, the contemplative seems shut off from the world, yet Steiner says that "What takes place in our inner life is not a mere [private] mental repetition, but a real part of the universal process."

For the mystic, the divine isn't something external to be repeated within; it is "something real in them to be awakened," says Bamford.

Angelus Silesius put it this way: "I know without me God cannot live for a moment; if I were to come to naught, God would have to give up the ghost. ... God cannot make a single worm without me; if I do not preserve it with God, it would fall apart immediately."

Bamford ends with the statement: "In fact, the world is falling apart, and it is up to us to preserve it."

Two things present themselves from this present exploration:

1) Silesius is talking about a kind of reciprocity not unlike Lao Tzu's.

2) My writing life is my vehicle of awakening and my mode of reciprocity. If the world is falling apart, as Bamford suggests, maybe it's through writing that I do my part to preserve it.

Nature is not humane; we should be like nature

I was reading an interview with Ursula K. LeGuin about her new rendition of the Tao Te Ching. Her version does more to stress feminine power. During the interview, LeGuin refers to a passage where Lao Tzu says we should be like nature, although nature isn't humane. That means Lao Tzu is saying self-sacrifice is not a good thing, but, in LeGuin's words, a "lousy thing."

I was intrigued by this because I've always felt drawn to self-sacrifice. It's often where I derive meaning for myself. LeGuin does help me to see self-sacrifice in a new light; well, perhaps not new, because I have thought about the nature of sacrifice before and wondered about its dark side. Says LeGuin:

Nature is definitely not humane. And Lao Tzu says we should be like nature. We should not be humane, either, in the sense that we should not sacrifice ourselves for others. Now that's going to be very hard for Christian readers to accept, because they're taught that self-sacrifice is a good thing. Lao Tzu says it's a lousy thing. This is perhaps the most radical thing he says to a Western ear. Don't buy into self-sacrifice. Any more than you would ask somebody to sacrifice themselves for you. There's a sort of reciprocity--that's the only way I can understand it.

I've been thinking about this since Mother Teresa's recent death. I have never been comfortable with her or with any extreme altruism. It makes me feel inferior, like I ought to be like that, but I'm not. And if I tried to be, it would be the most horrible hypocrisy. But why, what is it that I'm uncomfortable with? And I think maybe Lao Tzu gives me a little handle on that. In a sense, this kind of self-sacrifice occurs only in a society that is so sick that only somebody going too far can make up for the cruelty of the society.

This is startling to me. I've just been reading Karen Armstrong, who goes through each religion and shows how sacrifice became a defining feature. If LeGuin is right, then Lao Tzu's perception of religion is different from the others. It rests on reciprocity, not sacrifice.

Nature is beautiful and sometimes entertaining, but it isn't humane. This, it seems to me, is a truth that's become lost to us. Because we don't live with nature anymore, we've forgotten it's not a place of sacrifice, forgiveness, or grace. The recent deaths of Timothy Treadwell (Grizzly Man) and Steve Irwin (Crocodile Man) illustrate this. Both men have been criticized and blamed for their own deaths. Each man loved nature and sought to preserve it, but in also making it a form of sport and entertainment, they forgot reciprocity. Animals ought to be respected according to their natures, not turned into playthings or teddy bears. Both men forgot how we're connected to things. I believe we all suffer from the same blindness.

I recall an experience I had with the editors of The Sun magazine. They'd accepted a story of mine for publication and the story was going through the editing phase. I can't remember how I'd originally worded the sentence, but it was about give and take, getting something and giving something in return. It was about someone giving a gift on their own birthday, instead of just sitting back and receiving. The editors suggested the word "reciprocity." Looking at the word inserted into my own sentence by the editors, I rather gasped. What a beautiful word. That one word changed a simple idea into something clearly defined, and sacred.

But it isn't until right now, this moment, that I begin to think about what reciprocity means and how this concept might guide my life and my writing.

What if I didn't think of writing as an obligation or as a sacrifice I make by locking myself in a silent room for many hours. What if it is an act of reciprocity? Of giving back, of attempting to reveal some vision or insight I have been given?

I was intrigued by this because I've always felt drawn to self-sacrifice. It's often where I derive meaning for myself. LeGuin does help me to see self-sacrifice in a new light; well, perhaps not new, because I have thought about the nature of sacrifice before and wondered about its dark side. Says LeGuin:

Nature is definitely not humane. And Lao Tzu says we should be like nature. We should not be humane, either, in the sense that we should not sacrifice ourselves for others. Now that's going to be very hard for Christian readers to accept, because they're taught that self-sacrifice is a good thing. Lao Tzu says it's a lousy thing. This is perhaps the most radical thing he says to a Western ear. Don't buy into self-sacrifice. Any more than you would ask somebody to sacrifice themselves for you. There's a sort of reciprocity--that's the only way I can understand it.

I've been thinking about this since Mother Teresa's recent death. I have never been comfortable with her or with any extreme altruism. It makes me feel inferior, like I ought to be like that, but I'm not. And if I tried to be, it would be the most horrible hypocrisy. But why, what is it that I'm uncomfortable with? And I think maybe Lao Tzu gives me a little handle on that. In a sense, this kind of self-sacrifice occurs only in a society that is so sick that only somebody going too far can make up for the cruelty of the society.

This is startling to me. I've just been reading Karen Armstrong, who goes through each religion and shows how sacrifice became a defining feature. If LeGuin is right, then Lao Tzu's perception of religion is different from the others. It rests on reciprocity, not sacrifice.

Nature is beautiful and sometimes entertaining, but it isn't humane. This, it seems to me, is a truth that's become lost to us. Because we don't live with nature anymore, we've forgotten it's not a place of sacrifice, forgiveness, or grace. The recent deaths of Timothy Treadwell (Grizzly Man) and Steve Irwin (Crocodile Man) illustrate this. Both men have been criticized and blamed for their own deaths. Each man loved nature and sought to preserve it, but in also making it a form of sport and entertainment, they forgot reciprocity. Animals ought to be respected according to their natures, not turned into playthings or teddy bears. Both men forgot how we're connected to things. I believe we all suffer from the same blindness.

I recall an experience I had with the editors of The Sun magazine. They'd accepted a story of mine for publication and the story was going through the editing phase. I can't remember how I'd originally worded the sentence, but it was about give and take, getting something and giving something in return. It was about someone giving a gift on their own birthday, instead of just sitting back and receiving. The editors suggested the word "reciprocity." Looking at the word inserted into my own sentence by the editors, I rather gasped. What a beautiful word. That one word changed a simple idea into something clearly defined, and sacred.

But it isn't until right now, this moment, that I begin to think about what reciprocity means and how this concept might guide my life and my writing.

What if I didn't think of writing as an obligation or as a sacrifice I make by locking myself in a silent room for many hours. What if it is an act of reciprocity? Of giving back, of attempting to reveal some vision or insight I have been given?

Spirit Matters

From Demetria Martinez's essay, "Spirit Matters":

The writer's imagination must be roomy and supple enough for hope and joy as well as gloom and doom.

Our imaginations must be on call at all times, open to any possibility. So we fight sloth and fear and struggle to show up each day, before the blank page. If a writer can be said to have a spiritual practice, this is it: to stay awake until the imagination stirs and characters come alive in our hands. My hope is that by writing well I will help keep you, the reader, awake--and in love with the human project despite the dark times in which we live.

The writer's imagination must be roomy and supple enough for hope and joy as well as gloom and doom.

Our imaginations must be on call at all times, open to any possibility. So we fight sloth and fear and struggle to show up each day, before the blank page. If a writer can be said to have a spiritual practice, this is it: to stay awake until the imagination stirs and characters come alive in our hands. My hope is that by writing well I will help keep you, the reader, awake--and in love with the human project despite the dark times in which we live.

Buffy, Pinsky, Gluck, and me

So, I taught my Friday afternoon class and came home, looking forward to the weekend. Allen busied himself with the boat, getting it ready for to take out for a couple of nights. Just him and our dog, Buddha.

I stayed home, cooked something, ate, fiddled around on the Internet, downloaded some Buffy Sainte Marie songs ("Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee," "Starwalker," "Cod'ine," "He's a Keeper of the Fire," "God Is Alive, Magic Is Afoot," "Summer Boy," "Little Wheel, Spin and Spin," "Goodnight.") A dial up connection--hello?--it took a long time.

If you're a woman looking for strength, I highly recommend "Starwalker." It'll make you want to paint your naked body and dance and dare anybody to mess with you. From Buffy's website:

This is one of my [Buffy's] favourite songs, not only because it's a gas to sing it, but also because it's about the incredible energy of our contemporary Indian people. Because of what our ancestors went through for us. I sing it for all our generations past, and all our generations yet to come.

Starwalker he’s a friend of mine

You’ve seen him looking fine he’s a

straight talker

he’s a Starwalker don't drink no wine

ay way hey o heya

Wolf Rider she’s a friend of yours

You’ve seen her opening doors

She’s a history turner

she’s a sweetgrass burner and a

dog soldier

ay hey way hey way heya

Holy light guard the night

Pray up your medicine song oh

straight dealer you’re a spirit healer

keep going on

ay hey way hey way heya

Lightning Woman Thunderchild

Star soldiers one and all oh

Sisters, Brothers all together

Aim straight Stand tall

Starwalker he’s a friend of mine

You’ve seen him looking fine he’s a

straight talker

He’s a Starwalker don't drink no wine

ay way hey o hey...

You have to hear it. The chanting is amazing.

Later, I watched a movie about Edvard Munch. Then I slept until late, fed the cats, watered cats and flowers and pepper plants and tomatoes, checked the mail. Back on the cement slab outside our back door, I heard a strange sound, an animal. It was the rooster, calling to the hens. They were separated from each other and seeking each other out.

I came inside and turned on the Internet. I found this article by Robert Pinsky on Bloglines and the article drew me in and in until I found myself needing to write about it.

Pinsky writes about myths and allusions, how they do their work even if we don't fully understand the implications behind them. He uses a poem by Louise Gluck as illustration.

It's quite something to go from Buffy Sainte Marie lifting her voice in a collective warrior's cry to Gluck's quiet and deep exploration of women's lives. The Persephone Myth is spun into new cloth as the woman first imagines she was abducted by life, then that she offered herself. Two very different paths. Shouldn't each path yield a different arrival? Gluck writes of the "horrible mantle of daughterliness clinging to her." How intriguing. We usually think of Demeter's love for her daughter, of joyful reunion in Spring, not of a burden of belonging. So what is this horrible mantle? I understand it, but with my heart and not my head; I understand with a mystical kind of knowing. The power of myth.

Gluck takes us through the cycle of marriage: Death, husband, God, Stranger. The woman looks into the water, hoping for something about herself to be revealed. What? Who am I? Daughter, wife, mother, self--which? all?

"I am never alone," the woman has thought, then turned the thought into prayer. She sought to escape her body, to merge into someone else's. She's belonged to others, never herself. She wants to be alone, yet is lonely.

Well, time to make a little supper. I miss Allen and Buddha. I miss their physical energy, their play, Allen's laughter. I feel lonely, like the woman at the pool. Later, I'll cradle a book or do some writing, grade some papers. They will be home Sunday, and I will have gotten a lot done, I hope.

---------------------------------

Poet's Choice

By Robert Pinsky

Sunday, September 17, 2006; BW12

A really good allusion works even if you can't identify it. Like myths, allusions change with each repetition. The chariot of the sun, the bitter withy, Tippecanoe and Tyler too, Pandora's box, the Manassas Mauler: They mean more after you have looked them up, but they contain enough hints of sound and image to succeed on their own. Anybody can make a good guess, for example, at which of these phrases are political, mythological or biblical.

Sometimes, the wrong guess is a revealing part of making sense: If a great prizefighter's nickname sounds a little classical or biblical, alluding to him that way becomes part of his meaning. The sound and aroma of the syllables affects the myth.

Without some skill at guessing, who could navigate through any ordinary day with its words and images? Sometimes sorting and guessing is part of the point. The myths and allusions and meanings may be several. They may be invented, merging or overlapping. Here is "A Myth of Innocence," from Louise Glück's recent book Averno :

One summer she goes into the field as usual

stopping for a bit at the pool where she often

looks at herself, to see

if she detects any changes. She sees

the same person, the horrible mantle

of daughterliness still clinging to her.

The sun seems, in the water, very close.

That's my uncle spying again, she thinks--

everything in nature is in some way her relative.

I am never alone, she thinks,

turning the thought into a prayer.

Then death appears, like the answer to a prayer.

No one understands anymore

how beautiful he was. But Persephone remembers.

Also that he embraced her, right there,

with her uncle watching. She remembers

sunlight flashing on his bare arms.

This is the last moment she remembers clearly.

Then the dark god bore her away.

She also remembers, less clearly,

the chilling insight that from this moment

she couldn't live without him again.

The girl who disappears from the pool

will never return. A woman will return,

looking for the girl she was.

She stands by the pool saying, from time to time,

I was abducted, but it sounds

wrong to her, nothing like what she felt.

Then she says, I was not abducted.

Then she says, I offered myself, I wanted

to escape my body. Even, sometimes,

I willed this. But ignorance

cannot will knowledge. Ignorance

wills something imagined, which it believes exists.

All the different nouns--

she says them in rotation.

Death, husband, god, stranger.

Everything sounds so simple, so conversational.

I must have been, she thinks, a simple girl.

She can't remember herself as that person

but she keeps thinking the pool will remember

and explain to her the meaning of her prayer

so she can understand

whether it was answered or not.

The pleasure is partly in the playful distance between writer and character. "Allude" shares its root with "ludic" and "ludicrous," the vocabulary of play. The alternate things the character says, the "different nouns" she tries, the trickiness of a word such as "simple": These illustrate the shimmery nature of meaning, which inspires the devisings of myth, as well as the pranks of allusion.

(Louise Glück's poem "A Myth of Innocence" is from her book "Averno." Farrar Straus Giroux. Copyright © 2006 by Louise Glück.)

I stayed home, cooked something, ate, fiddled around on the Internet, downloaded some Buffy Sainte Marie songs ("Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee," "Starwalker," "Cod'ine," "He's a Keeper of the Fire," "God Is Alive, Magic Is Afoot," "Summer Boy," "Little Wheel, Spin and Spin," "Goodnight.") A dial up connection--hello?--it took a long time.

If you're a woman looking for strength, I highly recommend "Starwalker." It'll make you want to paint your naked body and dance and dare anybody to mess with you. From Buffy's website:

This is one of my [Buffy's] favourite songs, not only because it's a gas to sing it, but also because it's about the incredible energy of our contemporary Indian people. Because of what our ancestors went through for us. I sing it for all our generations past, and all our generations yet to come.

Starwalker he’s a friend of mine

You’ve seen him looking fine he’s a

straight talker

he’s a Starwalker don't drink no wine

ay way hey o heya

Wolf Rider she’s a friend of yours

You’ve seen her opening doors

She’s a history turner

she’s a sweetgrass burner and a

dog soldier

ay hey way hey way heya

Holy light guard the night

Pray up your medicine song oh

straight dealer you’re a spirit healer

keep going on

ay hey way hey way heya

Lightning Woman Thunderchild

Star soldiers one and all oh

Sisters, Brothers all together

Aim straight Stand tall

Starwalker he’s a friend of mine

You’ve seen him looking fine he’s a

straight talker

He’s a Starwalker don't drink no wine

ay way hey o hey...

You have to hear it. The chanting is amazing.

Later, I watched a movie about Edvard Munch. Then I slept until late, fed the cats, watered cats and flowers and pepper plants and tomatoes, checked the mail. Back on the cement slab outside our back door, I heard a strange sound, an animal. It was the rooster, calling to the hens. They were separated from each other and seeking each other out.

I came inside and turned on the Internet. I found this article by Robert Pinsky on Bloglines and the article drew me in and in until I found myself needing to write about it.

Pinsky writes about myths and allusions, how they do their work even if we don't fully understand the implications behind them. He uses a poem by Louise Gluck as illustration.

It's quite something to go from Buffy Sainte Marie lifting her voice in a collective warrior's cry to Gluck's quiet and deep exploration of women's lives. The Persephone Myth is spun into new cloth as the woman first imagines she was abducted by life, then that she offered herself. Two very different paths. Shouldn't each path yield a different arrival? Gluck writes of the "horrible mantle of daughterliness clinging to her." How intriguing. We usually think of Demeter's love for her daughter, of joyful reunion in Spring, not of a burden of belonging. So what is this horrible mantle? I understand it, but with my heart and not my head; I understand with a mystical kind of knowing. The power of myth.

Gluck takes us through the cycle of marriage: Death, husband, God, Stranger. The woman looks into the water, hoping for something about herself to be revealed. What? Who am I? Daughter, wife, mother, self--which? all?

"I am never alone," the woman has thought, then turned the thought into prayer. She sought to escape her body, to merge into someone else's. She's belonged to others, never herself. She wants to be alone, yet is lonely.

Well, time to make a little supper. I miss Allen and Buddha. I miss their physical energy, their play, Allen's laughter. I feel lonely, like the woman at the pool. Later, I'll cradle a book or do some writing, grade some papers. They will be home Sunday, and I will have gotten a lot done, I hope.

---------------------------------

Poet's Choice

By Robert Pinsky

Sunday, September 17, 2006; BW12

A really good allusion works even if you can't identify it. Like myths, allusions change with each repetition. The chariot of the sun, the bitter withy, Tippecanoe and Tyler too, Pandora's box, the Manassas Mauler: They mean more after you have looked them up, but they contain enough hints of sound and image to succeed on their own. Anybody can make a good guess, for example, at which of these phrases are political, mythological or biblical.

Sometimes, the wrong guess is a revealing part of making sense: If a great prizefighter's nickname sounds a little classical or biblical, alluding to him that way becomes part of his meaning. The sound and aroma of the syllables affects the myth.

Without some skill at guessing, who could navigate through any ordinary day with its words and images? Sometimes sorting and guessing is part of the point. The myths and allusions and meanings may be several. They may be invented, merging or overlapping. Here is "A Myth of Innocence," from Louise Glück's recent book Averno :

One summer she goes into the field as usual

stopping for a bit at the pool where she often

looks at herself, to see

if she detects any changes. She sees

the same person, the horrible mantle

of daughterliness still clinging to her.

The sun seems, in the water, very close.

That's my uncle spying again, she thinks--

everything in nature is in some way her relative.

I am never alone, she thinks,

turning the thought into a prayer.

Then death appears, like the answer to a prayer.

No one understands anymore

how beautiful he was. But Persephone remembers.

Also that he embraced her, right there,

with her uncle watching. She remembers

sunlight flashing on his bare arms.

This is the last moment she remembers clearly.

Then the dark god bore her away.

She also remembers, less clearly,

the chilling insight that from this moment

she couldn't live without him again.

The girl who disappears from the pool

will never return. A woman will return,

looking for the girl she was.

She stands by the pool saying, from time to time,

I was abducted, but it sounds

wrong to her, nothing like what she felt.

Then she says, I was not abducted.

Then she says, I offered myself, I wanted

to escape my body. Even, sometimes,

I willed this. But ignorance

cannot will knowledge. Ignorance

wills something imagined, which it believes exists.

All the different nouns--

she says them in rotation.

Death, husband, god, stranger.

Everything sounds so simple, so conversational.

I must have been, she thinks, a simple girl.

She can't remember herself as that person

but she keeps thinking the pool will remember

and explain to her the meaning of her prayer

so she can understand

whether it was answered or not.

The pleasure is partly in the playful distance between writer and character. "Allude" shares its root with "ludic" and "ludicrous," the vocabulary of play. The alternate things the character says, the "different nouns" she tries, the trickiness of a word such as "simple": These illustrate the shimmery nature of meaning, which inspires the devisings of myth, as well as the pranks of allusion.

(Louise Glück's poem "A Myth of Innocence" is from her book "Averno." Farrar Straus Giroux. Copyright © 2006 by Louise Glück.)

Friday, September 15, 2006

Invocation

O nourishing river

Mother of all that is written

Inspire fluent, truthful words.

May I discover the sacred river of wisdom within.

-- Invocation of Saraswati, the Hindu Goddess of Inspiration

Mother of all that is written

Inspire fluent, truthful words.

May I discover the sacred river of wisdom within.

-- Invocation of Saraswati, the Hindu Goddess of Inspiration

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Books are alive

I was riding in the elevator at the university with a stranger the other day. She seemed about the age of most graduate students, mid twenties, perhaps. She wore a bright long scarf over her hair and had dark skin. Perhaps Indian, I thought. She had those eyes, honest and sincere, as though she were looking into me. And she kept looking into me, so I smiled.

She said, "You teach literature, don't you?" I said I did, and she asked if I liked doing that. I said I did like it very much, that literature teaches us the meaning of the world. She smiled radiantly and said, "It teaches us the meaning of LIFE."

We who love literature know its power to teach and to change. You can still give this gift to yourself. Remember how you loved to read and write when you were young, and embrace it all again in newness and wonder. It's still good. Books are alive.

She said, "You teach literature, don't you?" I said I did, and she asked if I liked doing that. I said I did like it very much, that literature teaches us the meaning of the world. She smiled radiantly and said, "It teaches us the meaning of LIFE."

We who love literature know its power to teach and to change. You can still give this gift to yourself. Remember how you loved to read and write when you were young, and embrace it all again in newness and wonder. It's still good. Books are alive.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Expanding the reach of who you are

Tonight I watched Faith and Doubt at Ground Zero on PBS for the second time. The first time I saw it was several months ago. It's a powerful exploration of how people's belief in God changed after 9/11. Kirk Varnedoe, the former director of the Museum of Modern Art, had the following to say about art and religion:

People say art is a substitute religion, and I thought about a lot about that in the aftermath of 9/11. It's true that art transports you, that it gives you the sense that you can find other worlds than the ones that you know are inside of you. There are so many imagined worlds. Each artist creates a world with its own logic and its own set of rules in which you can move in and inhabit. They find form that lets you imaginatively take part in experiences with which you may not have had any contact, and for a moment, conceive of a world as pearlescent and as beautifully, rectilinearly ordered as a Piero. To feel these things through art expands the reach of who you are.

But art doesn't only transport you to new, imagined places. It also, in the best sense, narrows your vision, focuses with a new immediacy on the things that may be the most familiar to you. It gives a new spiritual dimension to the objects that you touch, to the room that you inhabit. And this is not just a tidy or comfortable experience but can be suffused with a kind Dionysian pleasure, in the sense of the small world controlled and the poetry of the world possessed, this crossing over of the line between what is the love of the material thing, of the dust mote in the sunlight or the sheen of the porcelain, of the look of the ivy winding around the bowl of fish, you know, this sort of pleasure in the daily small things. In art, through art, I think, transmutes itself into a form of spirituality, one to which I respond very, very strongly. --KIRK VARNEDOE, former directer of MoMA

I believe this transport was also experienced by van Gogh. In his letters he speaks so much about the power of color to transport him; he had a special affinity for yellow. Van Gogh's experience with art is particularly intriguing, since he once wanted to go into the ministry. Can it be that art became his religion?

The poets Dickey, Roethke, and James Wright spoke of poetry transporting them. Dickey described being on a city street with Wright and Robert Bly and sinking to his knees in awe of poetry. I've read many of James Wright's letters, in which he speaks of reading, or writing, a poem and of transcending the ordinary. James Agee, who also wrote poetry, but who is mostly known for his prose works, like Death in the Family, also wrote of how his struggle with art led him to ephiphany.

In my own case, I feel a sense of rightness and connectedness when the writing is going well. It's as though the neurons in my brain are firing in just the right pattern, allowing me to experience many things at once, and through this explosive integration, I'm able to see the "truth." (In a recent Sun article, the author says scientists have actually observed this phenomenon in the brain.) Joseph Campbell called this a "peak" moment, and he connected it with the transcendent. When I reach this point while writing, it feels similar to moments I used to have in church back in the late 1970s when I felt a sudden rush of love.

I have to think about whether I agree that art is a "substitute" religion. Vernedoe doesn't say whether or not he agrees, but he does say that we can experience a form of spirituality through art. I do really like what Varnedoe says about what art does, that it expands the imagination and at the same time it narrows your vision. It gives you a chance to focus on very specific things so that you can see how sacred they are. At the same time, it opens you to mystery. Yes, I really like that explanation.

People say art is a substitute religion, and I thought about a lot about that in the aftermath of 9/11. It's true that art transports you, that it gives you the sense that you can find other worlds than the ones that you know are inside of you. There are so many imagined worlds. Each artist creates a world with its own logic and its own set of rules in which you can move in and inhabit. They find form that lets you imaginatively take part in experiences with which you may not have had any contact, and for a moment, conceive of a world as pearlescent and as beautifully, rectilinearly ordered as a Piero. To feel these things through art expands the reach of who you are.

But art doesn't only transport you to new, imagined places. It also, in the best sense, narrows your vision, focuses with a new immediacy on the things that may be the most familiar to you. It gives a new spiritual dimension to the objects that you touch, to the room that you inhabit. And this is not just a tidy or comfortable experience but can be suffused with a kind Dionysian pleasure, in the sense of the small world controlled and the poetry of the world possessed, this crossing over of the line between what is the love of the material thing, of the dust mote in the sunlight or the sheen of the porcelain, of the look of the ivy winding around the bowl of fish, you know, this sort of pleasure in the daily small things. In art, through art, I think, transmutes itself into a form of spirituality, one to which I respond very, very strongly. --KIRK VARNEDOE, former directer of MoMA

I believe this transport was also experienced by van Gogh. In his letters he speaks so much about the power of color to transport him; he had a special affinity for yellow. Van Gogh's experience with art is particularly intriguing, since he once wanted to go into the ministry. Can it be that art became his religion?

The poets Dickey, Roethke, and James Wright spoke of poetry transporting them. Dickey described being on a city street with Wright and Robert Bly and sinking to his knees in awe of poetry. I've read many of James Wright's letters, in which he speaks of reading, or writing, a poem and of transcending the ordinary. James Agee, who also wrote poetry, but who is mostly known for his prose works, like Death in the Family, also wrote of how his struggle with art led him to ephiphany.

In my own case, I feel a sense of rightness and connectedness when the writing is going well. It's as though the neurons in my brain are firing in just the right pattern, allowing me to experience many things at once, and through this explosive integration, I'm able to see the "truth." (In a recent Sun article, the author says scientists have actually observed this phenomenon in the brain.) Joseph Campbell called this a "peak" moment, and he connected it with the transcendent. When I reach this point while writing, it feels similar to moments I used to have in church back in the late 1970s when I felt a sudden rush of love.

I have to think about whether I agree that art is a "substitute" religion. Vernedoe doesn't say whether or not he agrees, but he does say that we can experience a form of spirituality through art. I do really like what Varnedoe says about what art does, that it expands the imagination and at the same time it narrows your vision. It gives you a chance to focus on very specific things so that you can see how sacred they are. At the same time, it opens you to mystery. Yes, I really like that explanation.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

Yes and No

Today Allen and I talked a little about the inevitability of death and how bereft we would each feel without the other. It's a talk most married couples have, I think, and there have been some beautiful poems written about it (but I'm not up to doing that). Since our talk, I've wondered how I might have put into words his importance to me without falling back on all the old cliches.

I've been keeping a separate rather secret blog here at blogspot for a few weeks that I call "Meditations." It's a storehouse of observations and quotes pertaining to my current reading and thinking. It's not enabled for comments and I've not said anything about it because I doubt profoundly that anyone would be interested in it. There's no continuity to it and no commentary. But it does provide me with a place to hopefully find a way of threading together various ideas. I also keep a hard copy of "Meditations" in a little black notebook.

One idea I've been exploring for a long time is writing as a sacred act and as a way of knowing the deepest aspects of ourselves. I began "Meditations" this summer after doing a lot of reading on Theodore Roethke. I've also been picking through letters recently of van Gogh and Edvard Munch. Much earlier, I'd read the letters of Dickey, James Wright, and James Agee.

I went to "Meditations" tonight and reread what van Gogh said about the eternal yes and the eternal no.

Vincent van Gogh writes to Theo of Tersteeg, an art dealer with whom he'd had several unpleasant encounters. Vincent tells what he believes Tersteeg thinks of him and of what Tersteeg has come to represent to Vincent:

[Tersteeg thinks to himself] "You are a mediocrity and you are arrogant because you don't give in and you make mediocre little things: you are making yourself ridiculous with your so-called seeking, and you do not work."

Vincent goes on to say, That is the real meaning of what Tersteeg said to me the year before last, and last year; and he still means it.

I am afraid Tersteeg will always be for me "the everlasting no."

That is what not only I, but almost everyone who seeks his own way, has behind or beside him as an everlasting discourager. Sometimes one is depressed by it and feels miserable and almost stunned.

It's what Vincent says next that makes me think about Allen:

But I repeat, it is the everlasting no; in the cases of men of character, on the contrary, one finds an everlasting yes, and discovers in them "la foi du charbonnier."

For me Allen has been the everlasting yes. He has supported my writing completely, with a believer's faith, since the start. "La foi du charbonnier" means believing in something with a kind of religious acceptance, believing without "thinking" too much.

There have also been many Tersteegs in my life, and sometimes even now when I go about my "seeking," I can hear them deriding me or laughing at me. This is why it's so important to have someone who believes in you. It's so much easier, then, to fend off thoughts of the Tersteegs.

I write this not so much to call attention to my relationship with Allen and not to be depressing with all this talk about death, but to say that we all need that person in whom we find "La foi du charbonnier." I think for Vincent, it was Theo. For me it is Allen.

I've been keeping a separate rather secret blog here at blogspot for a few weeks that I call "Meditations." It's a storehouse of observations and quotes pertaining to my current reading and thinking. It's not enabled for comments and I've not said anything about it because I doubt profoundly that anyone would be interested in it. There's no continuity to it and no commentary. But it does provide me with a place to hopefully find a way of threading together various ideas. I also keep a hard copy of "Meditations" in a little black notebook.

One idea I've been exploring for a long time is writing as a sacred act and as a way of knowing the deepest aspects of ourselves. I began "Meditations" this summer after doing a lot of reading on Theodore Roethke. I've also been picking through letters recently of van Gogh and Edvard Munch. Much earlier, I'd read the letters of Dickey, James Wright, and James Agee.

I went to "Meditations" tonight and reread what van Gogh said about the eternal yes and the eternal no.

Vincent van Gogh writes to Theo of Tersteeg, an art dealer with whom he'd had several unpleasant encounters. Vincent tells what he believes Tersteeg thinks of him and of what Tersteeg has come to represent to Vincent:

[Tersteeg thinks to himself] "You are a mediocrity and you are arrogant because you don't give in and you make mediocre little things: you are making yourself ridiculous with your so-called seeking, and you do not work."

Vincent goes on to say, That is the real meaning of what Tersteeg said to me the year before last, and last year; and he still means it.

I am afraid Tersteeg will always be for me "the everlasting no."

That is what not only I, but almost everyone who seeks his own way, has behind or beside him as an everlasting discourager. Sometimes one is depressed by it and feels miserable and almost stunned.

It's what Vincent says next that makes me think about Allen:

But I repeat, it is the everlasting no; in the cases of men of character, on the contrary, one finds an everlasting yes, and discovers in them "la foi du charbonnier."

For me Allen has been the everlasting yes. He has supported my writing completely, with a believer's faith, since the start. "La foi du charbonnier" means believing in something with a kind of religious acceptance, believing without "thinking" too much.

There have also been many Tersteegs in my life, and sometimes even now when I go about my "seeking," I can hear them deriding me or laughing at me. This is why it's so important to have someone who believes in you. It's so much easier, then, to fend off thoughts of the Tersteegs.

I write this not so much to call attention to my relationship with Allen and not to be depressing with all this talk about death, but to say that we all need that person in whom we find "La foi du charbonnier." I think for Vincent, it was Theo. For me it is Allen.

Friday, September 08, 2006

Didn't You Want to Be a Writer?

This post is mostly for Erin of "Erin's Everyday Thoughts." She has been wondering where the last 5 years of her life have evaporated to and what has happened to her dream of being a writer. This post is also for anyone who has ever dreamed of being a writer. I ran into an article by Laura Zigman, talking about how we run into naysayers who tell us to be practical and get jobs that actually pay money, rather than entertain the notion of being a writer. Erin, it's so much like what I told you in my comment to your blog, and here it is again, that moment when you look up from the life you've created for yourself and you realize you have to write: You just have to. Here is part of the article:

If you are like most people (me), before you know it, you will agree wholeheartedly with your naysayers. "What was I thinking?" you will say to yourself every time the urge to write surfaces like an unruly weed, which you and everyone else keep trying to beat to death. "What could I possibly have to say that hasn't already been said by people a thousand times smarter than I will ever be?" Psychologists refer to this as the Stockholm Syndrome -- when captives begin to share the views of their captors. You will so fully internalize their message and adopt it as your own that you will eventually forget it wasn't your opinion to begin with.

You will now enter a long (seemingly placid but emotionally turbulent) period of denial that can sometimes last years (or decades). You will lie. "Who me? Be a writer? And put up with all that rejection? Are you kidding?" You will obfuscate. "Who would want to be a writer? Can you imagine being someone who wanted to be a writer?" When pressed, you will even philosophize: "If a writer writes something that never gets published and is thus never read, is a writer still a writer?"

In order to convince yourself and others that you have "moved on" (accepted defeat without even trying), you will learn to hide in plain sight: You will get a normal job, one with an actual office and an actual desk (engaging in "freelance work" from your apartment or working "odd jobs" with "odd hours" are dead giveaways of your true intentions and unconscious desires). In exchange for your 40 (or 50 or 60) hours a week of work (indentured servitude), you'll receive a respectable paycheck (let's be frank: not much more than you made waitressing in high school at the International House of Pancakes or working the drive-thru at Burger King) and medical benefits (to pay for psychotherapy, twice a week, to deal with the stress of all your repression). Most important, your job will provide you with some financial security and emotional stability (not to mention the perfect opportunity for people watching, eavesdropping, Internet research and working on something -- Fiction? Nonfiction? Comedy? Tragedy? -- even if you don't yet know what that something is).

In addition to the macro-lie (yourself as Career Drone), you'll see that you need to make up lots of little lies to protect your true identity (Secret Writer Person). You'll have to appear ambitious and deserving of promotions (show up before noon); pretend to embrace any and all career-enhancing business trips and client interactions (even though you see any time away from your true calling as a soul-deadening, blood-sucking diversion); and continue to dress the part (never complaining about how dumb it is that you have to spend all your money on work clothes when you could be home writing your novel in your pajamas).

And then one day, out of the blue, just when you think you're finally lost in the jungle, you will see it. You will look at all the papers and files and meaningless detritus on your desk, you will watch all your wonderfully idiosyncratic co-workers racing busily around the office, talking of Michelangelo, and you will stop whatever it is you are doing. The world you've tried so hard to join will suddenly cease to exist, and you will finally see that life without your dream is a wasteland; that you must at least try to do the thing you really want to do even if, in the end, you do not succeed at it. You will be tempted to put the better-to-have-loved-and-lost rule in parentheses, like everything else in your life that you've sidelined and tried to ignore up until now, but you will resist and settle for multiple hyphens instead. It is a step. You are about to head into the great unknown, and you will be tempted to throw away the map to your lost world in triumph, but don't -- you will need something to write on . --Laura Zigman

If you are like most people (me), before you know it, you will agree wholeheartedly with your naysayers. "What was I thinking?" you will say to yourself every time the urge to write surfaces like an unruly weed, which you and everyone else keep trying to beat to death. "What could I possibly have to say that hasn't already been said by people a thousand times smarter than I will ever be?" Psychologists refer to this as the Stockholm Syndrome -- when captives begin to share the views of their captors. You will so fully internalize their message and adopt it as your own that you will eventually forget it wasn't your opinion to begin with.

You will now enter a long (seemingly placid but emotionally turbulent) period of denial that can sometimes last years (or decades). You will lie. "Who me? Be a writer? And put up with all that rejection? Are you kidding?" You will obfuscate. "Who would want to be a writer? Can you imagine being someone who wanted to be a writer?" When pressed, you will even philosophize: "If a writer writes something that never gets published and is thus never read, is a writer still a writer?"

In order to convince yourself and others that you have "moved on" (accepted defeat without even trying), you will learn to hide in plain sight: You will get a normal job, one with an actual office and an actual desk (engaging in "freelance work" from your apartment or working "odd jobs" with "odd hours" are dead giveaways of your true intentions and unconscious desires). In exchange for your 40 (or 50 or 60) hours a week of work (indentured servitude), you'll receive a respectable paycheck (let's be frank: not much more than you made waitressing in high school at the International House of Pancakes or working the drive-thru at Burger King) and medical benefits (to pay for psychotherapy, twice a week, to deal with the stress of all your repression). Most important, your job will provide you with some financial security and emotional stability (not to mention the perfect opportunity for people watching, eavesdropping, Internet research and working on something -- Fiction? Nonfiction? Comedy? Tragedy? -- even if you don't yet know what that something is).

In addition to the macro-lie (yourself as Career Drone), you'll see that you need to make up lots of little lies to protect your true identity (Secret Writer Person). You'll have to appear ambitious and deserving of promotions (show up before noon); pretend to embrace any and all career-enhancing business trips and client interactions (even though you see any time away from your true calling as a soul-deadening, blood-sucking diversion); and continue to dress the part (never complaining about how dumb it is that you have to spend all your money on work clothes when you could be home writing your novel in your pajamas).

And then one day, out of the blue, just when you think you're finally lost in the jungle, you will see it. You will look at all the papers and files and meaningless detritus on your desk, you will watch all your wonderfully idiosyncratic co-workers racing busily around the office, talking of Michelangelo, and you will stop whatever it is you are doing. The world you've tried so hard to join will suddenly cease to exist, and you will finally see that life without your dream is a wasteland; that you must at least try to do the thing you really want to do even if, in the end, you do not succeed at it. You will be tempted to put the better-to-have-loved-and-lost rule in parentheses, like everything else in your life that you've sidelined and tried to ignore up until now, but you will resist and settle for multiple hyphens instead. It is a step. You are about to head into the great unknown, and you will be tempted to throw away the map to your lost world in triumph, but don't -- you will need something to write on . --Laura Zigman

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

The world is waiting...

The world is waiting to be known;

Earth, what it has in it!

The past is in it;

All words, feelings, movements,

words, bodies, clothes, girls, trees,

stones, things of beauty, books, desires are in it;

and all are to be known;

Afternoons have to do with the whole world;

And the beauty of mind,

feeling knowingly the world!

Eli Siegel

Earth, what it has in it!

The past is in it;

All words, feelings, movements,

words, bodies, clothes, girls, trees,

stones, things of beauty, books, desires are in it;

and all are to be known;

Afternoons have to do with the whole world;

And the beauty of mind,

feeling knowingly the world!

Eli Siegel

Making One of Opposites

Sanctuary

One of the most truly beautiful words in the English language, to me, is "sanctuary." I ran across a quote recently from artist Philip Guston:

"As a boy I would hide in the closet when the older brothers and sisters came with their families to mama's apartment for the Sunday afternoon dinner visit. I felt safe. Hearing their talk about illnesses, marriages, and the problems of making a living, I felt my remoteness in the closet with the single light bulb. I read and drew in this private box. Some Sundays I even painted. I had given my dear Mama passionate instructions to lie.... 'Where is Philip?' I could hear them.... 'Oh, he is away, with friends'....I was happy in my sanctuary. After a lifetime, I still have never been able to escape....It is still a struggle to be hidden and feel strange--my favorite mood."

I strongly relate to what Guston said. I never shut myself in a closet, except once when a girlfriend and I hid in my closet and practiced kissing by using the backs of our hands; but as a child I used to shut myself in my room for hours, and when my mother had company I could hear them saying, "Where's Theresa?" My mother made excuses for me, like Guston's did for him. She'd tell them I was reading or doing important school work. I loved peeling myself away from human contact in this way and having time to think, to draw pictures, to paint, to read, to dawdle.

I still do this. I love how Guston says his favorite mood is feeling "strange." I never thought of feeling strange as being a mood, but I guess it is. I also like the feeling of being strange, or apart.

I like the feeling of being alone, of having a sanctuary against the outside world.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Pages

Dreaming

About Me

- Theresa Williams

- Northwest Ohio, United States

- "I was no better than dust, yet you cannot replace me. . . Take the soft dust in your hand--does it stir: does it sing? Has it lips and a heart? Does it open its eyes to the sun? Does it run, does it dream, does it burn with a secret, or tremble In terror of death? Or ache with tremendous decisions?. . ." --Conrad Aiken

Followers

Facebook Badge

Search This Blog

Favorite Lines

My Website

Epistle, by Archibald MacLeish

Visit my Channel at YouTube

Great Artists

www.flickr.com

This is a Flickr badge showing public photos from theresarrt7. Make your own badge here.

Fave Painting: Eden

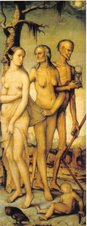

Fave Painting: The Three Ages of Man and Death

by Albrecht Dürer

From the First Chapter

The Secret of Hurricanes : That article in the Waterville Scout said it was Shake- spearean, all that fatalism that guides the Kennedys' lives. The likelihood of untimely death. Recently, another one died in his prime, John-John in an airplane. Not long before that, Bobby's boy. While playing football at high speeds on snow skis. Those Kennedys take some crazy chances. I prefer my own easy ways. Which isn't to say my life hasn't been Shake-spearean. By the time I was sixteen, my life was like the darkened stage at the end of Hamlet or Macbeth. All littered with corpses and treachery.

My Original Artwork: Triptych

Wishing

Little Deer

Transformation

Looking Forward, Looking Back

Blog Archive

-

▼

2006

(96)

-

▼

September

(20)

- Apocalyptic Thinking

- When Nations grow Old...

- The Permanent Realities of Every Thing

- Tombs

- Meant for Now

- Go Into a Wilderness

- We act just like the flower does in blooming

- Mysticism and Scholarship

- Nature is not humane; we should be like nature

- Spirit Matters

- Buffy, Pinsky, Gluck, and me

- Invocation

- Books are alive

- Expanding the reach of who you are

- "Into all abysses I still carry the blessings of m...

- Yes and No

- Didn't You Want to Be a Writer?

- The world is waiting...

- Making One of Opposites

- Sanctuary

-

▼

September

(20)

CURRENT MOON

Labels

- adolescence (1)

- Airstream (7)

- Alain de Botton (1)

- all nighters (2)

- Allen (1)

- altars (1)

- Angelus Silesius (2)

- animals (1)

- Annie Dillard (1)

- Antonio Machado (2)

- AOL Redux (1)

- April Fool (1)

- Archibald MacLeish (1)

- arts and crafts (55)

- Auden (1)

- awards (2)

- AWP (2)

- Bach (1)

- Basho (5)

- Beauty and the Beast (1)

- birthdays (1)

- blogs (5)

- boats (2)

- body (2)

- books (7)

- bookstores (1)

- Buddha (1)

- Buddha's Little Instruction Book (2)

- butterfly (4)

- buzzard (2)

- Capote (4)

- Carmel (1)

- Carson McCullers (1)

- cats (15)

- Charles Bukowski (1)

- Charles Simic (2)

- Christina Georgina Rossetti (1)

- church (2)

- confession (1)

- Conrad Aiken (1)

- cooking (5)

- crows (1)

- current events (2)

- D. H. Lawrence (3)

- death (6)

- Delmore Schwartz (4)

- detachment (1)

- dogs (7)

- domestic (3)

- dreams (21)

- Edward Munch (4)

- Edward Thomas (1)

- Eliot (3)

- Eliot's Waste Land (2)

- Emerson (2)

- Emily Dickinson (10)

- ephemera (1)

- Esalen (6)

- essay (3)

- Eugene O'Neill (3)

- Ezra Pound (1)

- F. Scott Fitzgerald (1)

- fairy tales (7)

- Fall (16)

- Famous Quotes (16)

- festivals (2)

- fire (5)

- Floreta (1)

- food (1)

- found notes etc. (1)

- found poem (2)

- fragments (86)

- Frida Kahlo (1)

- frogs-toads (4)

- Georg Trakl (1)

- gifts (1)

- Global Warming (1)

- Gluck (1)

- goats (1)

- Goodwill (1)

- Great lines of poetry (2)

- Haibun (15)

- haibun moleskine journal 2010 (2)

- Haiku (390)

- Hamlet (1)

- Hart Crane (4)

- Hayden Carruth (1)

- Henry Miller (1)

- holiday (12)

- Hyman Sobiloff (1)

- Icarus (1)

- ikkyu (5)

- Imagination (7)

- Ingmar Bergman (1)

- insect (2)

- inspiration (1)

- Issa (5)

- iTunes (1)

- Jack Kerouac (1)

- James Agee (2)

- James Dickey (5)

- James Wright (6)

- John Berryman (3)

- Joseph Campbell Meditation (2)

- journaling (1)

- Jung (1)

- Juniper Tree (1)

- Kafka (1)

- Lao Tzu (1)

- letters (1)

- light (1)

- Lorca (1)

- Lorine Niedecker (2)

- love (3)

- Lucille Clifton (1)

- Marco Polo Quarterly (1)

- Marianne Moore (1)

- Modern Poetry (14)

- moon (6)

- movies (20)

- Muriel Stuart (1)

- muse (3)

- music (8)

- Mystic (1)

- mythology (6)

- nature (3)

- New Yorker (2)

- Nietzsche (1)

- Northfork (2)

- November 12 (1)

- October (6)

- original artwork (21)

- original poem (53)

- Our Dog Buddha (6)

- Our Dog Sweet Pea (7)

- Our Yard (6)

- PAD 2009 (29)

- pad 2010 (30)

- Persephone (1)

- personal story (1)

- philosophy (1)

- Phoku (2)

- photographs (15)

- Picasso (2)

- Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1)

- Pillow Book (5)

- Pinsky (2)

- plays (1)

- poem (11)

- poet-seeker (9)

- poet-seer (6)

- poetry (55)

- politics (1)

- poppies (2)

- presentations (1)

- Provincetown (51)

- Publications (new and forthcoming) (13)

- rain (4)

- Randall Jarrell (1)

- reading (6)

- recipes (1)

- Reciprocity (1)

- Richard Brautigan (3)

- Richard Wilbur (2)

- Rilke (5)

- river (5)

- river novel (1)

- rivers (12)

- Robert Frost (2)

- Robert Rauschenberg (1)

- Robert Sean Leonard (1)

- Robinson Jeffers (1)

- Rollo May (2)

- Rumi (1)

- Ryokan (1)

- Sexton (1)

- short stories (13)

- skeletons (2)

- sleet (1)

- snake (1)

- Snow (24)

- solitude (1)

- spider (2)

- spring (1)

- Stanley Kunitz (1)

- students (2)

- suffering (4)

- suicide (2)

- summer (20)

- Sylvia Plath (2)

- Talking Writing (1)

- Tao (3)

- teaching (32)

- television (4)

- the artist (2)

- The Bridge (3)

- The Letter Project (4)

- The Shining (1)

- Thelma and Louise (1)

- Theodore Roethke (16)

- Thomas Gospel (1)

- Thomas Hardy (1)

- toys (3)

- Transcendentalism (1)

- Trickster (2)

- Trudell (1)

- Ursula LeGuin (1)

- vacation (10)

- Vermont (6)

- Virginia Woolf (1)

- Vonnegut (2)

- Wallace Stevens (1)

- Walt Whitman (8)

- weather (7)

- website (3)

- what I'm reading (2)

- William Blake (2)

- William Butler Yeats (5)

- wind (3)

- wine (2)

- winter (24)

- wood (3)

- Writing (111)

- Zen (1)