Out my window:

slow train passing

under pale sun, gray sky

Saturday, February 28, 2009

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

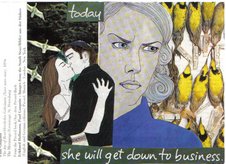

This day

Variation On a Poem by

Ann Lauterbach

This day I am sure of myself.

This day I am sure of myself.

I know what insecurity is.

It is bad weather.

I know what bad weather is.

This day I am sure of myself.

You leave the house happy.

Soon there is gnashing of teeth.

I can't help my insecurity.

This day I am sure of myself.

What will happen tomorrow?

There will be gnashing of teeth.

Tomorrow is its own country.

This day I am sure of myself.

Tomorrow is its own country.

Tomorrow has its own weather.

Tomorrow's weather is uncertain.

Today is a sound of people gnashing.

Everyone is insecure.

Everyone gnashes their teeth over losses.

Everyone's losses

will be felt tomorrow.

Snow is white ash.

This day I am sure of myself.

Snow floats down.

The sound is burning ash.

The sky is gnashing its teeth.

Today I am sure of myself.

The sky is a mouth.

The weather uncertain.

What is this ash?

The sky has lips and a mouth.

Today I am sure of myself.

My pain is yesterday.

My pain is insecurity.

Today is yesterday.

Here is the glove

That doesn't have a hand.

Here is the stove.

When is yesterday coming?

Here is my poem.

It has no book to live in.

Here is my path.

The gravel is loose.

Here is our truck.

It carries me home.

Here is the place

where I brush my teeth.

The wood is white like teeth.

The wood burns in the stove.

Empty the ashes.

Today I am sure of myself.

Ann Lauterbach

This day I am sure of myself.

This day I am sure of myself.

I know what insecurity is.

It is bad weather.

I know what bad weather is.

This day I am sure of myself.

You leave the house happy.

Soon there is gnashing of teeth.

I can't help my insecurity.

This day I am sure of myself.

What will happen tomorrow?

There will be gnashing of teeth.

Tomorrow is its own country.

This day I am sure of myself.

Tomorrow is its own country.

Tomorrow has its own weather.

Tomorrow's weather is uncertain.

Today is a sound of people gnashing.

Everyone is insecure.

Everyone gnashes their teeth over losses.

Everyone's losses

will be felt tomorrow.

Snow is white ash.

This day I am sure of myself.

Snow floats down.

The sound is burning ash.

The sky is gnashing its teeth.

Today I am sure of myself.

The sky is a mouth.

The weather uncertain.

What is this ash?

The sky has lips and a mouth.

Today I am sure of myself.

My pain is yesterday.

My pain is insecurity.

Today is yesterday.

Here is the glove

That doesn't have a hand.

Here is the stove.

When is yesterday coming?

Here is my poem.

It has no book to live in.

Here is my path.

The gravel is loose.

Here is our truck.

It carries me home.

Here is the place

where I brush my teeth.

The wood is white like teeth.

The wood burns in the stove.

Empty the ashes.

Today I am sure of myself.

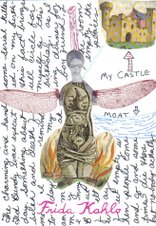

Museum Ephemera

My ticket and Allen's for the Munch Exhibit

The term ephemera derives from the Greek ephemeros, "for the day." It passes through our hands all the time. Most of the time we barely acknowledge it. Once in a while it seems to warrant keeping. I guess ephemera is a device for organizing our lives and memories. Running across ephemera from our own past days is a happy/sad experience. It's another one of those aspects of being human that fascinates me--why we save things.

A good one

Allen and I were talking last night before we went to sleep about Lent and Passover. We decided we didn't know much about them. So today I googled them and was telling Allen that Lent is the 40 days before Easter and that it signifies the 40 days that Christ spent in the wilderness.

Allen said, "Isn't there something else in the Bible about 40 days? How long was the flood?"

So I looked it up and sure enough the rain fell upon the earth for 40 days and 40 nights.

Allen said, "That must have been what happened to the dinosaurs."

I said, "Wouldn't Noah have put dinosaurs on the ark?"

Allen said, "Not necessarily."

I said, "Why did Noah put roaches on the ark: that's what I want to know."

Allen said, "He didn't mean to."

I laughed so hard when he said that, and he said, "What?"

I said, "Allen, that's a good one. That's a good joke."

He said, "It is? I don't get it."

He is so funny when he's not trying to be funny.

Allen said, "Isn't there something else in the Bible about 40 days? How long was the flood?"

So I looked it up and sure enough the rain fell upon the earth for 40 days and 40 nights.

Allen said, "That must have been what happened to the dinosaurs."

I said, "Wouldn't Noah have put dinosaurs on the ark?"

Allen said, "Not necessarily."

I said, "Why did Noah put roaches on the ark: that's what I want to know."

Allen said, "He didn't mean to."

I laughed so hard when he said that, and he said, "What?"

I said, "Allen, that's a good one. That's a good joke."

He said, "It is? I don't get it."

He is so funny when he's not trying to be funny.

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

Haiku #125

I step outside with the dog--silence.

Then far away, something cracks--

The dog barks: It's darker and colder now.

Then far away, something cracks--

The dog barks: It's darker and colder now.

25 Books of Poems and 1 Book of Stories that Made Me Want to Be a Poet

This prompt is going around Facebook, and I was tagged.

25 Books of Poems and 1 Book of Stories that Made Me Want to Be a Poet

1. Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman

2. Duino Elegies, Rilke

3. The Essential Rumi, trans. Coleman Barks

4. 2o Love Poems and a Song of Despair, Pablo Neruda

5. The World of the Ten Thousand Things, Charles Wright

6. Migration, W. S. Merwin

7. Loosestrife, Stephen Dunn

8. The Great Fires, Jack Gilbert

9. Book of Nightmares, Galway Kinnell

10. Collected Poems, Stanley Kunitz

11. Without End, Adam agajewski

12. The Wild Iris, Louise Gluck

13. Sonnets to Orpheus, Rilke

14. Hafiz of Shiraz, trans. Peter Avery & John Heath-Stubbs

15. Questions for Ecclesiastes, Mark Jarman

16. Show Yourself to My Soul, Rabindranath Tagore

17. Above the River, James Wright

18. Birdsong, Rumi

19. The Selected Poems of Federico Garcia Lorca

20. There is No Road, Antonio Machado

21. Narrow Road to the Interior, Matsuo Basho, trans. Sam Hamill

22. Book of Hours, Rilke

23. Love-In-Idleness, John Bradley

24. Dream Songs, John Berryman

25. The Beforelife, Franz Wright

1. Winesburg, Ohio, Sherwood Anderson

25 Books of Poems and 1 Book of Stories that Made Me Want to Be a Poet

1. Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman

2. Duino Elegies, Rilke

3. The Essential Rumi, trans. Coleman Barks

4. 2o Love Poems and a Song of Despair, Pablo Neruda

5. The World of the Ten Thousand Things, Charles Wright

6. Migration, W. S. Merwin

7. Loosestrife, Stephen Dunn

8. The Great Fires, Jack Gilbert

9. Book of Nightmares, Galway Kinnell

10. Collected Poems, Stanley Kunitz

11. Without End, Adam agajewski

12. The Wild Iris, Louise Gluck

13. Sonnets to Orpheus, Rilke

14. Hafiz of Shiraz, trans. Peter Avery & John Heath-Stubbs

15. Questions for Ecclesiastes, Mark Jarman

16. Show Yourself to My Soul, Rabindranath Tagore

17. Above the River, James Wright

18. Birdsong, Rumi

19. The Selected Poems of Federico Garcia Lorca

20. There is No Road, Antonio Machado

21. Narrow Road to the Interior, Matsuo Basho, trans. Sam Hamill

22. Book of Hours, Rilke

23. Love-In-Idleness, John Bradley

24. Dream Songs, John Berryman

25. The Beforelife, Franz Wright

1. Winesburg, Ohio, Sherwood Anderson

Monday, February 23, 2009

Munch Exhibit, II

I'm looking through my copy of Edvard Munch: The Modern Life of the Soul, published by the Museum of Modern Art and I'm so disappointed now to be looking at representations of the works rather than the works themselves.

The Munch exhibit in Chicago was haunting and unforgettable and took me into the maelstrom of some difficult emotions. I've always felt this is a trip worth taking because the end result is exhilarating. I just can't shake the feeling of having seen Munch's work, the real canvases and papers of Munch.

I've always loved Munch's art. I think it is his preoccupation with sex and death that has drawn me to him. Sex and death has always been a preoccupation of mine and has shown itself in my fiction. When I was a young art student at East Carolina University, Munch's painting Puberty (1894-5) was always beside me. At the Chicago exhibit, I learned there is an etching (I think it is called Le Plus Bel Amour de Don Juan, created in 1886) that probably served as inspiration for Munch's work. The description of Le Plus Bel Amour suggested that the girl is afraid she has been impregnated because she has sat on a chair recently vacated by Don Juan.

Munch definitely made the subject his own; his girl is much more uncomfortable than the girl in Le Plus Bel Amour; I'd say she's morbidly shy. The shadow behind her is a Munch touch. It is menacing. It has been described as phallic.

The painting always spoke to me of my own shyness as a girl and my fear and fascination of sex from an early age.

Adolescence can be a scary time for girls.

The Munch exhibit in Chicago was haunting and unforgettable and took me into the maelstrom of some difficult emotions. I've always felt this is a trip worth taking because the end result is exhilarating. I just can't shake the feeling of having seen Munch's work, the real canvases and papers of Munch.

I've always loved Munch's art. I think it is his preoccupation with sex and death that has drawn me to him. Sex and death has always been a preoccupation of mine and has shown itself in my fiction. When I was a young art student at East Carolina University, Munch's painting Puberty (1894-5) was always beside me. At the Chicago exhibit, I learned there is an etching (I think it is called Le Plus Bel Amour de Don Juan, created in 1886) that probably served as inspiration for Munch's work. The description of Le Plus Bel Amour suggested that the girl is afraid she has been impregnated because she has sat on a chair recently vacated by Don Juan.

Munch definitely made the subject his own; his girl is much more uncomfortable than the girl in Le Plus Bel Amour; I'd say she's morbidly shy. The shadow behind her is a Munch touch. It is menacing. It has been described as phallic.

The painting always spoke to me of my own shyness as a girl and my fear and fascination of sex from an early age.

Adolescence can be a scary time for girls.

Edvard Munch Exhibit

I was so fortunate to be able to see the Edvard Munch exhibit when I was in Chicago for AWP. Here is a review of the exhibit from the NY Times:

CHICAGO — Society tends to prefer creative types who neatly fit the pigeonhole labeled Other. The artist as solitary, tormented, possibly insane genius is among the most durable staples of the modern imagination.

It is also comforting. That’s not me, you can tell yourself. I may not be creative, but at least I’m not crazy.

The modern foundation of this stereotype lies with Vincent van Gogh, but no one gave it more definition than the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944). It is the ambition of “Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety and Myth,” a thrilling exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, to upend or at least balance Munch’s famous persona, which he himself helped shape, with a more realistic portrayal. Munch’s well-known suffering began with a childhood scarred by poverty and the deaths from tuberculosis of his mother and a beloved sister, Sophie; was made harsher by the religious fervor of a stern father; and was mitigated by precocious talent and the encouragement of a loving aunt. There followed early and repeated disappointments in love; recurring illness of several varieties; debilitating melancholia and bouts of paranoia; another sister committed to a mental asylum. His alcoholism didn’t help. Perhaps fittingly Munch’s most emblematic image, “The Scream,” with its hallucinatory sky and shrieking button face, was vandalized early on with delicately scrawled graffiti that reads in Norwegian, “Could only have been painted by a madman.” (While there is no “Scream” painting in the show, one of his lithographs of that work is present.)

Most of Munch’s figures are not mad, but paralyzed by oceanic feelings of grief, jealousy, desire or despair that many people found shocking either for their eroticism, crude style or intimations of mental instability. We see his subjects alone, in couples or small groups in settings whose opulent colors and odd forms, whether indoors or out, are always removed from reality, located in some artificial, stripped down place where color, feeling and form resonate in visual echo chambers.

Munch’s art offers some of the world’s most effective images of emotional states — a veritable international sign language of the soul. In “Melancholy” a man, hunched over somewhat like Rodin’s “Thinker,” broods among rocks that surge toward him like sympathetic bivalves, beside an undulant body of water. In “Summer Night’s Dream: The Voice” a young woman in a white dress seems frozen in a moment of realization, her stillness echoed by the surrounding trees, her purity balanced by the sun’s pillarlike reflection on a lake.

The notion that there is more to Munch than his original detractors, or admirers, first realized — or than Munch himself let on — is not as new as Jay A. Clarke, who organized “Becoming Edvard Munch,” might like to believe. Studies of how other artists influenced his work appeared as early as 1960, as Ms. Clarke, associate curator of prints and drawings at the Art Institute, acknowledges in the exhibition’s catalog.

Still, Munch’s interaction with the art and the art worlds of his time may never have been traced so fully in exhibition form as it is here. Lavish and precise, this show centers on 86 works by Munch. Including nearly 40 oils and taking full advantage of the Art Institute’s great holdings in Munch prints, they range from 1888, the year of his second trip to Paris, to the early 1900s, when he was well established both at home and abroad.

Yet what makes this encounter with Munch so extraordinary are the non-Munchs: 61 works by 43 of his contemporaries. They include the French Impressionist Claude Monet; the great Belgian proto-Expressionist James Ensor; the German Symbolists Franz von Stuck and Max Klinger; Harriet Backer, a little-known Norwegian painter 18 years Munch’s senior, who, like him, studied in Paris and combined French innovation with a northern moodiness. Also here is Hans Heyerdahl, another Norwegian, represented by his harrowing “Dying Child,” of 1889, one of the few works by another artist that Munch admired in writing. It is seen here, among Munchs that it clearly inspired: “The Sick Child” and “Death in the Sickroom,” which depicted Sophie’s illness and death.

Munch was, in Ms. Clarke’s useful phrase, “a sponge” and a very peripatetic one. Moving primarily among Berlin, Paris, Copenhagen and Kristiania (as Oslo was known at the time), he staged exhibitions and worked with print publishers, setting up studios and getting down to work almost everywhere he went. But he also set down in Switzerland, Italy, Monte Carlo and at numerous spas and sanitariums. He probably knew Monet, was knocked out by Ensor and was lionized by the German Expressionists as their godfather. He wrote to his aunt that the scandal caused by his large 1892 exhibition in Berlin, shut down by the city’s art association, was good for business. It helped sell paintings and also allowed him to charge attendance for subsequent shows.

Spread throughout 14 large galleries, “Becoming Edvard Munch” can initially seem overwhelming, an intimidating rabbit hole of a show. Its thematic organization, often a dumbing-down device, is tremendously helpful here. So is the fact that the show moves in an arc from light to dark back to light again, from Munch’s absorption of the relativel sunniness of Monet’s and Caillebotte’s Impressionism, through his intersections with the German Symbolists and their themes of sickness, death and femme fatales, back to nature and light as part of the Norwegian emphasis on nature and Nordic myth and folklore.

Each gallery is almost a self-sufficient exhibition. The first features a display of self-portraits that establish the power of Munch’s personality and something of his self-infatuation. In the large 1895 self-portrait he stares beyond us like a conjuring magician. In an unusual woodcut he shrinks under the weight of a large room, like a Giacometti figure.

Elsewhere Munch’s painting “Kiss by the Window,” of 1892, with its powerful sweep of shadow, form and feeling, is compared with nearly identical motifs by Klinger and the French painter Albert Besnard, as well as a bronze of Rodin’s sculpture, “The Kiss.” Again and again you realize that the best way to explain a work of art is with another one.

And there are many works by Munch and other artists that are complete worlds. Ensor’s small, elegantly roiled “Christ Tormented” is one of these. It reminds you that Ensor can be a more inspired, or satisfying, painter than Munch, but his vision seems cramped and self-involved next to Munch’s widely applicable life lessons.

A fantastic van Gogh — “The Bridge at Trinquetaille,” of 1888 — reminds us that both artists had a penchant for images of vulnerable figures isolated toward the front of the picture, sometimes looking out at us. From the same year we see Munch’s “At the General Store in Vrengen,” with its staring child standing amid a wonderful patchwork of shadowy pastels. “Evening,” also from 1888, shows a woman staring intently off into the distance (albeit to the side). Much more realistic, it indicates both how quickly Munch was developing at this point, but also how fixed he already was on giving his figures an intense inner life.

With the Museum of Modern Art’s 2006 Munch retrospective and the High Museum’s 2002 examination of his undervalued late work, Munch has had a banner decade in the United States. The Chicago show is in many ways the most encompassing, in part because it focuses on so much more than one artist.“Becoming Edvard Munch” unleashes a remarkable play of ideas, mediums, styles and personalities, making the very idea of the traditional one-artist retrospective seem limited and fusty.

Here we see Munch navigating the messiness of his own present. Yet the exhibition also leaves no doubt about Munch’s singularity as a giant of the imagination and of modernism. Several artists here — Klinger for example — vacillate all over the dial from academic to radical. Munch simply broke the dial. His disdain for normal technique and finish, his love of long, somewhat slurpy brush strokes that were more stained than painted, made all the difference. They enable him to give new voice to the rawest emotions, to be dramatic without sentimentality, and to fuse process, subject and content.

Revealing the context of the outer Munch, this extraordinary show only intensifies our appreciation of the inner one, by making his emotional honesty and his radical approach to painting all the more obvious and undeniable.

“Becoming Edvard Munch” opens Saturday and continues through April 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago, 111 South Michigan Avenue. Dated and timed tickets are required for admission: (312) 443-3600 or artinstituteofchicago.org. The show does not travel.

CHICAGO — Society tends to prefer creative types who neatly fit the pigeonhole labeled Other. The artist as solitary, tormented, possibly insane genius is among the most durable staples of the modern imagination.

It is also comforting. That’s not me, you can tell yourself. I may not be creative, but at least I’m not crazy.

The modern foundation of this stereotype lies with Vincent van Gogh, but no one gave it more definition than the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944). It is the ambition of “Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety and Myth,” a thrilling exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, to upend or at least balance Munch’s famous persona, which he himself helped shape, with a more realistic portrayal. Munch’s well-known suffering began with a childhood scarred by poverty and the deaths from tuberculosis of his mother and a beloved sister, Sophie; was made harsher by the religious fervor of a stern father; and was mitigated by precocious talent and the encouragement of a loving aunt. There followed early and repeated disappointments in love; recurring illness of several varieties; debilitating melancholia and bouts of paranoia; another sister committed to a mental asylum. His alcoholism didn’t help. Perhaps fittingly Munch’s most emblematic image, “The Scream,” with its hallucinatory sky and shrieking button face, was vandalized early on with delicately scrawled graffiti that reads in Norwegian, “Could only have been painted by a madman.” (While there is no “Scream” painting in the show, one of his lithographs of that work is present.)

Most of Munch’s figures are not mad, but paralyzed by oceanic feelings of grief, jealousy, desire or despair that many people found shocking either for their eroticism, crude style or intimations of mental instability. We see his subjects alone, in couples or small groups in settings whose opulent colors and odd forms, whether indoors or out, are always removed from reality, located in some artificial, stripped down place where color, feeling and form resonate in visual echo chambers.

Munch’s art offers some of the world’s most effective images of emotional states — a veritable international sign language of the soul. In “Melancholy” a man, hunched over somewhat like Rodin’s “Thinker,” broods among rocks that surge toward him like sympathetic bivalves, beside an undulant body of water. In “Summer Night’s Dream: The Voice” a young woman in a white dress seems frozen in a moment of realization, her stillness echoed by the surrounding trees, her purity balanced by the sun’s pillarlike reflection on a lake.

The notion that there is more to Munch than his original detractors, or admirers, first realized — or than Munch himself let on — is not as new as Jay A. Clarke, who organized “Becoming Edvard Munch,” might like to believe. Studies of how other artists influenced his work appeared as early as 1960, as Ms. Clarke, associate curator of prints and drawings at the Art Institute, acknowledges in the exhibition’s catalog.

Still, Munch’s interaction with the art and the art worlds of his time may never have been traced so fully in exhibition form as it is here. Lavish and precise, this show centers on 86 works by Munch. Including nearly 40 oils and taking full advantage of the Art Institute’s great holdings in Munch prints, they range from 1888, the year of his second trip to Paris, to the early 1900s, when he was well established both at home and abroad.

Yet what makes this encounter with Munch so extraordinary are the non-Munchs: 61 works by 43 of his contemporaries. They include the French Impressionist Claude Monet; the great Belgian proto-Expressionist James Ensor; the German Symbolists Franz von Stuck and Max Klinger; Harriet Backer, a little-known Norwegian painter 18 years Munch’s senior, who, like him, studied in Paris and combined French innovation with a northern moodiness. Also here is Hans Heyerdahl, another Norwegian, represented by his harrowing “Dying Child,” of 1889, one of the few works by another artist that Munch admired in writing. It is seen here, among Munchs that it clearly inspired: “The Sick Child” and “Death in the Sickroom,” which depicted Sophie’s illness and death.

Munch was, in Ms. Clarke’s useful phrase, “a sponge” and a very peripatetic one. Moving primarily among Berlin, Paris, Copenhagen and Kristiania (as Oslo was known at the time), he staged exhibitions and worked with print publishers, setting up studios and getting down to work almost everywhere he went. But he also set down in Switzerland, Italy, Monte Carlo and at numerous spas and sanitariums. He probably knew Monet, was knocked out by Ensor and was lionized by the German Expressionists as their godfather. He wrote to his aunt that the scandal caused by his large 1892 exhibition in Berlin, shut down by the city’s art association, was good for business. It helped sell paintings and also allowed him to charge attendance for subsequent shows.

Spread throughout 14 large galleries, “Becoming Edvard Munch” can initially seem overwhelming, an intimidating rabbit hole of a show. Its thematic organization, often a dumbing-down device, is tremendously helpful here. So is the fact that the show moves in an arc from light to dark back to light again, from Munch’s absorption of the relativel sunniness of Monet’s and Caillebotte’s Impressionism, through his intersections with the German Symbolists and their themes of sickness, death and femme fatales, back to nature and light as part of the Norwegian emphasis on nature and Nordic myth and folklore.

Each gallery is almost a self-sufficient exhibition. The first features a display of self-portraits that establish the power of Munch’s personality and something of his self-infatuation. In the large 1895 self-portrait he stares beyond us like a conjuring magician. In an unusual woodcut he shrinks under the weight of a large room, like a Giacometti figure.

Elsewhere Munch’s painting “Kiss by the Window,” of 1892, with its powerful sweep of shadow, form and feeling, is compared with nearly identical motifs by Klinger and the French painter Albert Besnard, as well as a bronze of Rodin’s sculpture, “The Kiss.” Again and again you realize that the best way to explain a work of art is with another one.

And there are many works by Munch and other artists that are complete worlds. Ensor’s small, elegantly roiled “Christ Tormented” is one of these. It reminds you that Ensor can be a more inspired, or satisfying, painter than Munch, but his vision seems cramped and self-involved next to Munch’s widely applicable life lessons.

A fantastic van Gogh — “The Bridge at Trinquetaille,” of 1888 — reminds us that both artists had a penchant for images of vulnerable figures isolated toward the front of the picture, sometimes looking out at us. From the same year we see Munch’s “At the General Store in Vrengen,” with its staring child standing amid a wonderful patchwork of shadowy pastels. “Evening,” also from 1888, shows a woman staring intently off into the distance (albeit to the side). Much more realistic, it indicates both how quickly Munch was developing at this point, but also how fixed he already was on giving his figures an intense inner life.

With the Museum of Modern Art’s 2006 Munch retrospective and the High Museum’s 2002 examination of his undervalued late work, Munch has had a banner decade in the United States. The Chicago show is in many ways the most encompassing, in part because it focuses on so much more than one artist.“Becoming Edvard Munch” unleashes a remarkable play of ideas, mediums, styles and personalities, making the very idea of the traditional one-artist retrospective seem limited and fusty.

Here we see Munch navigating the messiness of his own present. Yet the exhibition also leaves no doubt about Munch’s singularity as a giant of the imagination and of modernism. Several artists here — Klinger for example — vacillate all over the dial from academic to radical. Munch simply broke the dial. His disdain for normal technique and finish, his love of long, somewhat slurpy brush strokes that were more stained than painted, made all the difference. They enable him to give new voice to the rawest emotions, to be dramatic without sentimentality, and to fuse process, subject and content.

Revealing the context of the outer Munch, this extraordinary show only intensifies our appreciation of the inner one, by making his emotional honesty and his radical approach to painting all the more obvious and undeniable.

“Becoming Edvard Munch” opens Saturday and continues through April 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago, 111 South Michigan Avenue. Dated and timed tickets are required for admission: (312) 443-3600 or artinstituteofchicago.org. The show does not travel.

Saturday, February 21, 2009

Fifteen Albums

AWP Chicago is now just a memory, but a very good memory. I came back thinking about AWP Denver and that I'd love to participate in Denver in some way. Our faculty reading and the memorial for O'Connor were enjoyable. The presentation I enjoyed most was the one given by "Women of a Certain Age":

Women of a Certain Age.

(Janet Burroway, Rosellen Brown, Hilma Wolitzer, Sandra Gilbert, Hilda Raz, Carole Simmons Oles) Six women writers over sixty, who are teachers and/or editors as well, share the long perspective. They will discuss how the publishing industry has changed over the course of their careers, how the relation between writing and feminism has affected them, how ambition has changed, how ambition persists, how they have handled disappointment, how they would do it differently, how differently they perceive life for young writers today.

It was encouraging to see women continuing to write and make themselves visible after the age of 60. Why do we write? Who are we writing for? These are two questions they sought to answer.

I got tagged at Facebook to list fifteen albums that are important to me:

Think of 15 albums, CDs, LPs (if you're over 40) that had such a profound effect on you they changed your life. Dug into your soul. Music that brought you to life when you heard it. Royally affected you, kicked you in the wazoo, literally socked you in the gut, is what I mean. Then when you finish, tag 15 others, including moi. Make sure you copy and paste this part so they know the drill. Get the idea now? Good. Tag, you're it!

1. Soundtrack from the movie Donnie Darko

2. Moondance, Van Morrison

3. Honeyman, Tim Buckley

4. Pink Moon, Nick Drake

5. Aqualung, Jethro Tull

6. The Rising, Bruce Springsteen

7. Modern Times, Bob Dylan

8. Tea for the Tillerman, Cat Stevens

9. Led Zeppelin IV, Led Zeppelin

10. A Momentary Lapse of Reason, Pink Floyd

11. Three Ragas, Ravi Shankar

12. Chronical, Creedence Clearwater

13. Boys for Pele, Tori Amos

14. Teaser and the Firecat, Cat Stevens

15. No One is Really Beautiful, Jude

Women of a Certain Age.

(Janet Burroway, Rosellen Brown, Hilma Wolitzer, Sandra Gilbert, Hilda Raz, Carole Simmons Oles) Six women writers over sixty, who are teachers and/or editors as well, share the long perspective. They will discuss how the publishing industry has changed over the course of their careers, how the relation between writing and feminism has affected them, how ambition has changed, how ambition persists, how they have handled disappointment, how they would do it differently, how differently they perceive life for young writers today.

It was encouraging to see women continuing to write and make themselves visible after the age of 60. Why do we write? Who are we writing for? These are two questions they sought to answer.

I got tagged at Facebook to list fifteen albums that are important to me:

Think of 15 albums, CDs, LPs (if you're over 40) that had such a profound effect on you they changed your life. Dug into your soul. Music that brought you to life when you heard it. Royally affected you, kicked you in the wazoo, literally socked you in the gut, is what I mean. Then when you finish, tag 15 others, including moi. Make sure you copy and paste this part so they know the drill. Get the idea now? Good. Tag, you're it!

1. Soundtrack from the movie Donnie Darko

2. Moondance, Van Morrison

3. Honeyman, Tim Buckley

4. Pink Moon, Nick Drake

5. Aqualung, Jethro Tull

6. The Rising, Bruce Springsteen

7. Modern Times, Bob Dylan

8. Tea for the Tillerman, Cat Stevens

9. Led Zeppelin IV, Led Zeppelin

10. A Momentary Lapse of Reason, Pink Floyd

11. Three Ragas, Ravi Shankar

12. Chronical, Creedence Clearwater

13. Boys for Pele, Tori Amos

14. Teaser and the Firecat, Cat Stevens

15. No One is Really Beautiful, Jude

Saturday, February 14, 2009

AWP in Chicago

I am in Chicago. It is that time when students and teachers of writing come together and talk about writing. It is the AWP (Association of Writers and Writer's Programs) conference. Look here for details about the conference.

This is only my second AWP conference. My first was also in Chicago. Next year it will be in Denver. Next, Washington D.C. The first year, I was an observer; this year I'll be on a panel called "The Bowling Green Five." We, the Bowling Green Five, are the core members of the Creative Writing program, and each of us will talk about a favorite writing assignment we give our students and then illustrate the assignment by reading something from our own work. We present tomorrow afternoon.

Today I went to three presentations. They were impressive and caused me to change my idea about my own presentation a dozen times. But I have gone all the way back to the beginning and will be doing what I originally planned. After the presentation, I'm charged with sharing something about Philip F. O'Connor at an evening reception. He was my teacher and mentor when I was a graduate student.

I'll write as soon as I can about how it goes.

This is only my second AWP conference. My first was also in Chicago. Next year it will be in Denver. Next, Washington D.C. The first year, I was an observer; this year I'll be on a panel called "The Bowling Green Five." We, the Bowling Green Five, are the core members of the Creative Writing program, and each of us will talk about a favorite writing assignment we give our students and then illustrate the assignment by reading something from our own work. We present tomorrow afternoon.

Today I went to three presentations. They were impressive and caused me to change my idea about my own presentation a dozen times. But I have gone all the way back to the beginning and will be doing what I originally planned. After the presentation, I'm charged with sharing something about Philip F. O'Connor at an evening reception. He was my teacher and mentor when I was a graduate student.

I'll write as soon as I can about how it goes.

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Mysterious Life of the Heart III. Some remarks I made.

Here are some remarks I made on Tuesday at a faculty presentation on "Blue Velvis," which appears this month in The Mysterious Life of the Heart.

The first books I remember reading are volumes of The World Book Encyclopedia. They were red and blue with gold lettering, and, besides one thick book on carpentry, they were the only books in our house. They were very official-looking.

World Book comforted me then and for many years afterwards. I took the volumes with me when I married, carried them with me Ohio. I only let them go ten years ago just before we were to move to the country. I set them on the curb and the a sanitation worker carried them away. I still miss those books. When I think of them now, I am reminded that order can be brought to the world. I remember that order not inherent in us but something we make.

The first writing I remember being excited about was a collection of short stories by Guy de Maupassant. My older brother found the book somewhere and gave it to me. Its cover was lime green. It was a very thick book. I couldn’t imagine anybody being able to write such a big book. I figured that was likely the only thing Maupassant did in his life, just write, write, write.

I was about twelve years old when I began reading Maupassant’s stories. The stories couldn’t have been more different from the calm, sensible entries in World Book. Maupassant’s stories were really wild. They were about love and death but mostly death, I remember. Bodies moldering the grave! Burning corpses! The book was so outrageous! I came to the conclusion it was pornographic and hid it under my bed.

What Maupassant showed me was I wasn’t the only person to feel terror of death. That was pretty comforting to a twelve year old who thought the cedar chest in her bedroom turned into a coffin at night. That cedar chest is in my house now; I’m no longer afraid of it, but there are other terrors I have from time to time. What Maupassant’s book continues to teach me that what is terrifying in life must be shared. Stories can help us to deal with what most frightens us.

I’m surprised I became a writer. I was going to be an artist. Like Leonardo DaVinci, I was going to draw and paint portraits. Even in the rural South, we had art classes, so “Artist” was something I knew a person could “be.” But we were never taught to write stories or poems, so I didn’t know a writer was something I could “be.”

Later, after I’d taken a creative writing class in college, I thought, “Okay, so maybe a writer is something I can be.” But for a long time, I didn’t think a woman’s experience was worth telling. Most of the stories I’d read in college were about men.

My novel (The Secret of Hurricanes, 2002) was my first work about a woman’s experience. Writing that book changed how I thought about my work. It wasn’t just that I learned a woman’s story was worth telling. I learned that I enjoy showing how characters adapt to change.

“Blue Velvis” is one of five stories that came to be written in my family bathtub. It’s about Nora Walker who has just had a hysterectomy. This subject certainly shows how far I’d come in my thinking about the importance of telling women’s stories. Have you ever thought about how few stories there are about hysterectomy? Not many. I found a few, but I thought the message of them was terrible. They seemed to say a woman was nothing without her womb. She couldn’t be a real woman without that thing inside of her.

I didn’t like that message. I thought it was time somebody wrote some better stories about the topic. In my stories, the woman wouldn’t be a sad victim of fate. She wouldn’t be considered useless. She’d fall, but at some point, she’d suit up and go into battle. Her terror would be real. I’d give dignity to her experience.

Nora really feels dead. She feels she’s lost her identity. She feels like an impersonator in her own life. That’s where the stories begin. By the fifth story, she recovers. It’s a really hard battle, but she prevails, finally.

I gave Nora a hapless boyfriend who loves her and wants to help. But he fails because no one can take our life-journeys for us. By the fifth story, Nora has an awakening. You might say a sudden awakening. But an awakening only seems sudden. It only seems that one moment you’re blind and then, inexplicably, the scales fall from your eyes and you can see, really see. Really, Nora’s realization is slow, and it is spread out over five stories.

I think this is pretty true to life. An awakening doesn’t happen as a result of one person, one event. It’s a synthesis of experience. It gets mixed with temperament and emotion. Sometimes it results in joy, but the outcome could just as well be anger, violence or tears.

These days, I still read and scribble a few things while soaking in my bathtub. But so far I haven’t repeated the experience of writing whole stories there. I wrote the Nora Walker stories in notebooks wrinkled as a result of getting wet. Sometimes I’d write all night, re-warming the water when necessary. Once, I dropped one of the notebooks in the water and rushed to my computer to get the words down before the inked words bled to nothingness on the page. I didn’t even wait to wrap myself in a towel.

Why the family bathtub? I might say that nakedness had something to do with it. But then all writers come to the page naked in one way or another. A willingness to be vulnerable is characteristic of fiction writers. It had to be something more, or something else.

The only reason I can think of is that I needed a womb in which to write. The bathtub was my womb. I must have sensed that a womb would be the only place to write stories about a woman who had lost hers. The bathtub would somehow make me spiritually and intellectually capable to write what I needed to write. This is only a guess, but it’s my best guess.

“Blue Velvis” has sailed off into the world and even made me some money. It won me an Ohio Arts Council grant. It was published in The Sun Magazine. It will appear this month in a new anthology published by The Sun. I can only conclude that people must find something in it that’s true to human experience. I think, maybe, like Nora, we’ve all been scared of change. We’ve all felt like we were strangers to ourselves. I think, maybe, like Lenny, we’ve wanted to help someone we love and found ourselves unable to do that. When we love someone, we want to be able to fix their problems. We feel helpless when we can’t do that.

The first books I remember reading are volumes of The World Book Encyclopedia. They were red and blue with gold lettering, and, besides one thick book on carpentry, they were the only books in our house. They were very official-looking.

World Book comforted me then and for many years afterwards. I took the volumes with me when I married, carried them with me Ohio. I only let them go ten years ago just before we were to move to the country. I set them on the curb and the a sanitation worker carried them away. I still miss those books. When I think of them now, I am reminded that order can be brought to the world. I remember that order not inherent in us but something we make.

The first writing I remember being excited about was a collection of short stories by Guy de Maupassant. My older brother found the book somewhere and gave it to me. Its cover was lime green. It was a very thick book. I couldn’t imagine anybody being able to write such a big book. I figured that was likely the only thing Maupassant did in his life, just write, write, write.

I was about twelve years old when I began reading Maupassant’s stories. The stories couldn’t have been more different from the calm, sensible entries in World Book. Maupassant’s stories were really wild. They were about love and death but mostly death, I remember. Bodies moldering the grave! Burning corpses! The book was so outrageous! I came to the conclusion it was pornographic and hid it under my bed.

What Maupassant showed me was I wasn’t the only person to feel terror of death. That was pretty comforting to a twelve year old who thought the cedar chest in her bedroom turned into a coffin at night. That cedar chest is in my house now; I’m no longer afraid of it, but there are other terrors I have from time to time. What Maupassant’s book continues to teach me that what is terrifying in life must be shared. Stories can help us to deal with what most frightens us.

I’m surprised I became a writer. I was going to be an artist. Like Leonardo DaVinci, I was going to draw and paint portraits. Even in the rural South, we had art classes, so “Artist” was something I knew a person could “be.” But we were never taught to write stories or poems, so I didn’t know a writer was something I could “be.”

Later, after I’d taken a creative writing class in college, I thought, “Okay, so maybe a writer is something I can be.” But for a long time, I didn’t think a woman’s experience was worth telling. Most of the stories I’d read in college were about men.

My novel (The Secret of Hurricanes, 2002) was my first work about a woman’s experience. Writing that book changed how I thought about my work. It wasn’t just that I learned a woman’s story was worth telling. I learned that I enjoy showing how characters adapt to change.

“Blue Velvis” is one of five stories that came to be written in my family bathtub. It’s about Nora Walker who has just had a hysterectomy. This subject certainly shows how far I’d come in my thinking about the importance of telling women’s stories. Have you ever thought about how few stories there are about hysterectomy? Not many. I found a few, but I thought the message of them was terrible. They seemed to say a woman was nothing without her womb. She couldn’t be a real woman without that thing inside of her.

I didn’t like that message. I thought it was time somebody wrote some better stories about the topic. In my stories, the woman wouldn’t be a sad victim of fate. She wouldn’t be considered useless. She’d fall, but at some point, she’d suit up and go into battle. Her terror would be real. I’d give dignity to her experience.

Nora really feels dead. She feels she’s lost her identity. She feels like an impersonator in her own life. That’s where the stories begin. By the fifth story, she recovers. It’s a really hard battle, but she prevails, finally.

I gave Nora a hapless boyfriend who loves her and wants to help. But he fails because no one can take our life-journeys for us. By the fifth story, Nora has an awakening. You might say a sudden awakening. But an awakening only seems sudden. It only seems that one moment you’re blind and then, inexplicably, the scales fall from your eyes and you can see, really see. Really, Nora’s realization is slow, and it is spread out over five stories.

I think this is pretty true to life. An awakening doesn’t happen as a result of one person, one event. It’s a synthesis of experience. It gets mixed with temperament and emotion. Sometimes it results in joy, but the outcome could just as well be anger, violence or tears.

These days, I still read and scribble a few things while soaking in my bathtub. But so far I haven’t repeated the experience of writing whole stories there. I wrote the Nora Walker stories in notebooks wrinkled as a result of getting wet. Sometimes I’d write all night, re-warming the water when necessary. Once, I dropped one of the notebooks in the water and rushed to my computer to get the words down before the inked words bled to nothingness on the page. I didn’t even wait to wrap myself in a towel.

Why the family bathtub? I might say that nakedness had something to do with it. But then all writers come to the page naked in one way or another. A willingness to be vulnerable is characteristic of fiction writers. It had to be something more, or something else.

The only reason I can think of is that I needed a womb in which to write. The bathtub was my womb. I must have sensed that a womb would be the only place to write stories about a woman who had lost hers. The bathtub would somehow make me spiritually and intellectually capable to write what I needed to write. This is only a guess, but it’s my best guess.

“Blue Velvis” has sailed off into the world and even made me some money. It won me an Ohio Arts Council grant. It was published in The Sun Magazine. It will appear this month in a new anthology published by The Sun. I can only conclude that people must find something in it that’s true to human experience. I think, maybe, like Nora, we’ve all been scared of change. We’ve all felt like we were strangers to ourselves. I think, maybe, like Lenny, we’ve wanted to help someone we love and found ourselves unable to do that. When we love someone, we want to be able to fix their problems. We feel helpless when we can’t do that.

Wednesday, February 04, 2009

The Mysterious Life of the Heart, II

My author-copy of The Mysterious Life of the Heart should arrive by the end of the week.

My author-copy of The Mysterious Life of the Heart should arrive by the end of the week. Here is part of the intro and the full table of contents:

Love is a house with many rooms, and The Mysterious Life of the Heart explores only one of them: not a child’s love for a parent or a parent’s love for a child or love between siblings or love between friends. It’s about the room upstairs at the end of the hall, shared by two lovers who’ve decided to stay — for a weekend or forever, no one can say. Sometimes they kiss, sometimes they bite. They dream they’re in heaven. They swear they’re in hell. That room.

The sheer volume of writing on this subject that’s appeared in The Sun made it difficult to decide what to include. Choosing fifty essays, short stories, and poems out of the hundreds we considered might have been easier if we hadn’t already fallen in love with and published them all. So we set to work reading and rereading, Venus sitting on one shoulder and Mars perched on the other, and when we finally finished making our choices, what did we end up with? Exactly twenty-five works by men and twenty-five by women. Well, how about that! We’d hit the bull’s-eye without even trying.

This isn’t a book in which you’ll find the seven steps to connubial bliss, with exercises at the end of each chapter to simultaneously tighten your buttocks and open your third eye. But that doesn’t mean the stories, essays, and poems are randomly arranged. Instead, we follow a winding, sometimes treacherous path from the innocence and impetuousness of young love through marriage and devotion, temptation and betrayal, divorce and heartbreak, and finally forgiveness and mercy. When read from front to back, The Mysterious Life of the Heart is a journey worth taking. (Naturally, you’re free to ignore our counsel, begin reading anywhere, and jump from piece to piece, just as you’re free to throw caution to the wind and jump into bed with the next attractive person you meet. Don’t say we didn’t warn you.)

Sy Safransky

Editor and publisher

Table of Contents

Ecstasy a short story by Steve Almond

How Far Did You Get? poetry by Christopher Bursk

Foreclosure Doug Crandell

Beach Boy Heather King

Still Life With Candles And Spanish Guitar a short story by Kirk Nesset Alone With Love Songs poetry by Edwin Romond

I Will Soon Be Married a short story by John Tait

The Leap poetry by Larry Colker

The Woman With Hair a short story by Robert McGee

The Boy With Blue Hair Cheryl Strayed

Evening Voices poetry by Jeff Walt

Ten Things a short story by Leslie Pietrzyk

My Fat Lover Leah Truth

Blue Velvis a short story by Theresa Williams

Box Step poetry by Todd James Pierce

Au Revoir, Pleasant Dreams Rosemary Berkeley

An Hour After Breakfast poetry by Matthew Deshe Cashion

The Empty House Of My Brokenhearted Father a short story by Poe Ballantine

Greed poetry by Kathryn Hunt

Suzy Joins The Sex Club a short story by Alison Clement

On Catching My Husband With A Cigarette After Seven Years Of Abstinence poetry by Patry Francis

Small Things a short story by Suniti Landgé

Her Shoes poetry by Alison Seevak

And Passion Most Of All Michelle Cacho-Negrete

Prayer For Your Wife poetry by Kathleen Lake

Everything I Thought Would Happen Ashley Walker

Self-Storage poetry by Lee Rossi

The Kitchen Table: An Honest Orgy Denise Gess

Marriage poetry by Lou Lipsitz

My Marital Status James Kullander

The Song Of Forgiveness Genie Zeiger

Bleeding Dharma Stephen T. Butterfield

Committed Relationships poetry by Eric Anderson

The Year In Geese a short story by Rita Townsend

Smashing The Plates poetry by Alison Luterman

Finding A Good Man Jasmine Skye

Eight Love Poems poetry by Sparrow

The Date Brenda Miller

The Word a short story by Robley Wilson

Under The Apple Tree a short story by Laura Pritchett

I Am Not A Sex Goddess Lois Judson

Blowing It In Idaho Stephen J. Lyons

The Woman In Question Tom Ireland

This Day poetry by John Hodgen

My Accidental Jihad Krista Bremer

The Stranger poetry by Michael Hettich

Blue Flamingo Looks At Red Water a short story by Katherine Vaz

Sixteenth Anniversary poetry by Tess Gallagher

Green a short story by Colin Chisholm

Hello, Gorgeous! a short story by Bruce Holland Rogers

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Pages

Dreaming

About Me

- Theresa Williams

- Northwest Ohio, United States

- "I was no better than dust, yet you cannot replace me. . . Take the soft dust in your hand--does it stir: does it sing? Has it lips and a heart? Does it open its eyes to the sun? Does it run, does it dream, does it burn with a secret, or tremble In terror of death? Or ache with tremendous decisions?. . ." --Conrad Aiken

Followers

Facebook Badge

Search This Blog

Favorite Lines

My Website

Epistle, by Archibald MacLeish

Visit my Channel at YouTube

Great Artists

www.flickr.com

This is a Flickr badge showing public photos from theresarrt7. Make your own badge here.

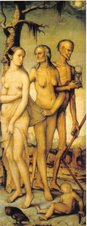

Fave Painting: Eden

Fave Painting: The Three Ages of Man and Death

by Albrecht Dürer

From the First Chapter

The Secret of Hurricanes : That article in the Waterville Scout said it was Shake- spearean, all that fatalism that guides the Kennedys' lives. The likelihood of untimely death. Recently, another one died in his prime, John-John in an airplane. Not long before that, Bobby's boy. While playing football at high speeds on snow skis. Those Kennedys take some crazy chances. I prefer my own easy ways. Which isn't to say my life hasn't been Shake-spearean. By the time I was sixteen, my life was like the darkened stage at the end of Hamlet or Macbeth. All littered with corpses and treachery.

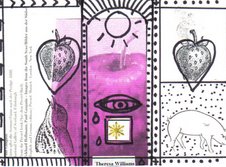

My Original Artwork: Triptych

Wishing

Little Deer

Transformation

Looking Forward, Looking Back

Blog Archive

-

▼

2009

(273)

-

▼

February

(18)

- Haiku #132

- Haiku #131

- Haiku #130

- Haiku #129

- Haiku #128

- This day

- Haiku #127

- Museum Ephemera

- A good one

- Haiku #126

- Haiku #125

- 25 Books of Poems and 1 Book of Stories that Made ...

- Munch Exhibit, II

- Edvard Munch Exhibit

- Fifteen Albums

- AWP in Chicago

- Mysterious Life of the Heart III. Some remarks I ...

- The Mysterious Life of the Heart, II

-

▼

February

(18)

CURRENT MOON

Labels

- adolescence (1)

- Airstream (7)

- Alain de Botton (1)

- all nighters (2)

- Allen (1)

- altars (1)

- Angelus Silesius (2)

- animals (1)

- Annie Dillard (1)

- Antonio Machado (2)

- AOL Redux (1)

- April Fool (1)

- Archibald MacLeish (1)

- arts and crafts (55)

- Auden (1)

- awards (2)

- AWP (2)

- Bach (1)

- Basho (5)

- Beauty and the Beast (1)

- birthdays (1)

- blogs (5)

- boats (2)

- body (2)

- books (7)

- bookstores (1)

- Buddha (1)

- Buddha's Little Instruction Book (2)

- butterfly (4)

- buzzard (2)

- Capote (4)

- Carmel (1)

- Carson McCullers (1)

- cats (15)

- Charles Bukowski (1)

- Charles Simic (2)

- Christina Georgina Rossetti (1)

- church (2)

- confession (1)

- Conrad Aiken (1)

- cooking (5)

- crows (1)

- current events (2)

- D. H. Lawrence (3)

- death (6)

- Delmore Schwartz (4)

- detachment (1)

- dogs (7)

- domestic (3)

- dreams (21)

- Edward Munch (4)

- Edward Thomas (1)

- Eliot (3)

- Eliot's Waste Land (2)

- Emerson (2)

- Emily Dickinson (10)

- ephemera (1)

- Esalen (6)

- essay (3)

- Eugene O'Neill (3)

- Ezra Pound (1)

- F. Scott Fitzgerald (1)

- fairy tales (7)

- Fall (16)

- Famous Quotes (16)

- festivals (2)

- fire (5)

- Floreta (1)

- food (1)

- found notes etc. (1)

- found poem (2)

- fragments (86)

- Frida Kahlo (1)

- frogs-toads (4)

- Georg Trakl (1)

- gifts (1)

- Global Warming (1)

- Gluck (1)

- goats (1)

- Goodwill (1)

- Great lines of poetry (2)

- Haibun (15)

- haibun moleskine journal 2010 (2)

- Haiku (390)

- Hamlet (1)

- Hart Crane (4)

- Hayden Carruth (1)

- Henry Miller (1)

- holiday (12)

- Hyman Sobiloff (1)

- Icarus (1)

- ikkyu (5)

- Imagination (7)

- Ingmar Bergman (1)

- insect (2)

- inspiration (1)

- Issa (5)

- iTunes (1)

- Jack Kerouac (1)

- James Agee (2)

- James Dickey (5)

- James Wright (6)

- John Berryman (3)

- Joseph Campbell Meditation (2)

- journaling (1)

- Jung (1)

- Juniper Tree (1)

- Kafka (1)

- Lao Tzu (1)

- letters (1)

- light (1)

- Lorca (1)

- Lorine Niedecker (2)

- love (3)

- Lucille Clifton (1)

- Marco Polo Quarterly (1)

- Marianne Moore (1)

- Modern Poetry (14)

- moon (6)

- movies (20)

- Muriel Stuart (1)

- muse (3)

- music (8)

- Mystic (1)

- mythology (6)

- nature (3)

- New Yorker (2)

- Nietzsche (1)

- Northfork (2)

- November 12 (1)

- October (6)

- original artwork (21)

- original poem (53)

- Our Dog Buddha (6)

- Our Dog Sweet Pea (7)

- Our Yard (6)

- PAD 2009 (29)

- pad 2010 (30)

- Persephone (1)

- personal story (1)

- philosophy (1)

- Phoku (2)

- photographs (15)

- Picasso (2)

- Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1)

- Pillow Book (5)

- Pinsky (2)

- plays (1)

- poem (11)

- poet-seeker (9)

- poet-seer (6)

- poetry (55)

- politics (1)

- poppies (2)

- presentations (1)

- Provincetown (51)

- Publications (new and forthcoming) (13)

- rain (4)

- Randall Jarrell (1)

- reading (6)

- recipes (1)

- Reciprocity (1)

- Richard Brautigan (3)

- Richard Wilbur (2)

- Rilke (5)

- river (5)

- river novel (1)

- rivers (12)

- Robert Frost (2)

- Robert Rauschenberg (1)

- Robert Sean Leonard (1)

- Robinson Jeffers (1)

- Rollo May (2)

- Rumi (1)

- Ryokan (1)

- Sexton (1)

- short stories (13)

- skeletons (2)

- sleet (1)

- snake (1)

- Snow (24)

- solitude (1)

- spider (2)

- spring (1)

- Stanley Kunitz (1)

- students (2)

- suffering (4)

- suicide (2)

- summer (20)

- Sylvia Plath (2)

- Talking Writing (1)

- Tao (3)

- teaching (32)

- television (4)

- the artist (2)

- The Bridge (3)

- The Letter Project (4)

- The Shining (1)

- Thelma and Louise (1)

- Theodore Roethke (16)

- Thomas Gospel (1)

- Thomas Hardy (1)

- toys (3)

- Transcendentalism (1)

- Trickster (2)

- Trudell (1)

- Ursula LeGuin (1)

- vacation (10)

- Vermont (6)

- Virginia Woolf (1)

- Vonnegut (2)

- Wallace Stevens (1)

- Walt Whitman (8)

- weather (7)

- website (3)

- what I'm reading (2)

- William Blake (2)

- William Butler Yeats (5)

- wind (3)

- wine (2)

- winter (24)

- wood (3)

- Writing (111)

- Zen (1)