I was so fortunate to be able to see the Edvard Munch exhibit when I was in Chicago for AWP. Here is a review of the exhibit from the NY Times:

CHICAGO — Society tends to prefer creative types who neatly fit the pigeonhole labeled Other. The artist as solitary, tormented, possibly insane genius is among the most durable staples of the modern imagination.

It is also comforting. That’s not me, you can tell yourself. I may not be creative, but at least I’m not crazy.

The modern foundation of this stereotype lies with Vincent van Gogh, but no one gave it more definition than the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944). It is the ambition of “Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety and Myth,” a thrilling exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, to upend or at least balance Munch’s famous persona, which he himself helped shape, with a more realistic portrayal. Munch’s well-known suffering began with a childhood scarred by poverty and the deaths from tuberculosis of his mother and a beloved sister, Sophie; was made harsher by the religious fervor of a stern father; and was mitigated by precocious talent and the encouragement of a loving aunt. There followed early and repeated disappointments in love; recurring illness of several varieties; debilitating melancholia and bouts of paranoia; another sister committed to a mental asylum. His alcoholism didn’t help. Perhaps fittingly Munch’s most emblematic image, “The Scream,” with its hallucinatory sky and shrieking button face, was vandalized early on with delicately scrawled graffiti that reads in Norwegian, “Could only have been painted by a madman.” (While there is no “Scream” painting in the show, one of his lithographs of that work is present.)

Most of Munch’s figures are not mad, but paralyzed by oceanic feelings of grief, jealousy, desire or despair that many people found shocking either for their eroticism, crude style or intimations of mental instability. We see his subjects alone, in couples or small groups in settings whose opulent colors and odd forms, whether indoors or out, are always removed from reality, located in some artificial, stripped down place where color, feeling and form resonate in visual echo chambers.

Munch’s art offers some of the world’s most effective images of emotional states — a veritable international sign language of the soul. In “Melancholy” a man, hunched over somewhat like Rodin’s “Thinker,” broods among rocks that surge toward him like sympathetic bivalves, beside an undulant body of water. In “Summer Night’s Dream: The Voice” a young woman in a white dress seems frozen in a moment of realization, her stillness echoed by the surrounding trees, her purity balanced by the sun’s pillarlike reflection on a lake.

The notion that there is more to Munch than his original detractors, or admirers, first realized — or than Munch himself let on — is not as new as Jay A. Clarke, who organized “Becoming Edvard Munch,” might like to believe. Studies of how other artists influenced his work appeared as early as 1960, as Ms. Clarke, associate curator of prints and drawings at the Art Institute, acknowledges in the exhibition’s catalog.

Still, Munch’s interaction with the art and the art worlds of his time may never have been traced so fully in exhibition form as it is here. Lavish and precise, this show centers on 86 works by Munch. Including nearly 40 oils and taking full advantage of the Art Institute’s great holdings in Munch prints, they range from 1888, the year of his second trip to Paris, to the early 1900s, when he was well established both at home and abroad.

Yet what makes this encounter with Munch so extraordinary are the non-Munchs: 61 works by 43 of his contemporaries. They include the French Impressionist Claude Monet; the great Belgian proto-Expressionist James Ensor; the German Symbolists Franz von Stuck and Max Klinger; Harriet Backer, a little-known Norwegian painter 18 years Munch’s senior, who, like him, studied in Paris and combined French innovation with a northern moodiness. Also here is Hans Heyerdahl, another Norwegian, represented by his harrowing “Dying Child,” of 1889, one of the few works by another artist that Munch admired in writing. It is seen here, among Munchs that it clearly inspired: “The Sick Child” and “Death in the Sickroom,” which depicted Sophie’s illness and death.

Munch was, in Ms. Clarke’s useful phrase, “a sponge” and a very peripatetic one. Moving primarily among Berlin, Paris, Copenhagen and Kristiania (as Oslo was known at the time), he staged exhibitions and worked with print publishers, setting up studios and getting down to work almost everywhere he went. But he also set down in Switzerland, Italy, Monte Carlo and at numerous spas and sanitariums. He probably knew Monet, was knocked out by Ensor and was lionized by the German Expressionists as their godfather. He wrote to his aunt that the scandal caused by his large 1892 exhibition in Berlin, shut down by the city’s art association, was good for business. It helped sell paintings and also allowed him to charge attendance for subsequent shows.

Spread throughout 14 large galleries, “Becoming Edvard Munch” can initially seem overwhelming, an intimidating rabbit hole of a show. Its thematic organization, often a dumbing-down device, is tremendously helpful here. So is the fact that the show moves in an arc from light to dark back to light again, from Munch’s absorption of the relativel sunniness of Monet’s and Caillebotte’s Impressionism, through his intersections with the German Symbolists and their themes of sickness, death and femme fatales, back to nature and light as part of the Norwegian emphasis on nature and Nordic myth and folklore.

Each gallery is almost a self-sufficient exhibition. The first features a display of self-portraits that establish the power of Munch’s personality and something of his self-infatuation. In the large 1895 self-portrait he stares beyond us like a conjuring magician. In an unusual woodcut he shrinks under the weight of a large room, like a Giacometti figure.

Elsewhere Munch’s painting “Kiss by the Window,” of 1892, with its powerful sweep of shadow, form and feeling, is compared with nearly identical motifs by Klinger and the French painter Albert Besnard, as well as a bronze of Rodin’s sculpture, “The Kiss.” Again and again you realize that the best way to explain a work of art is with another one.

And there are many works by Munch and other artists that are complete worlds. Ensor’s small, elegantly roiled “Christ Tormented” is one of these. It reminds you that Ensor can be a more inspired, or satisfying, painter than Munch, but his vision seems cramped and self-involved next to Munch’s widely applicable life lessons.

A fantastic van Gogh — “The Bridge at Trinquetaille,” of 1888 — reminds us that both artists had a penchant for images of vulnerable figures isolated toward the front of the picture, sometimes looking out at us. From the same year we see Munch’s “At the General Store in Vrengen,” with its staring child standing amid a wonderful patchwork of shadowy pastels. “Evening,” also from 1888, shows a woman staring intently off into the distance (albeit to the side). Much more realistic, it indicates both how quickly Munch was developing at this point, but also how fixed he already was on giving his figures an intense inner life.

With the Museum of Modern Art’s 2006 Munch retrospective and the High Museum’s 2002 examination of his undervalued late work, Munch has had a banner decade in the United States. The Chicago show is in many ways the most encompassing, in part because it focuses on so much more than one artist.“Becoming Edvard Munch” unleashes a remarkable play of ideas, mediums, styles and personalities, making the very idea of the traditional one-artist retrospective seem limited and fusty.

Here we see Munch navigating the messiness of his own present. Yet the exhibition also leaves no doubt about Munch’s singularity as a giant of the imagination and of modernism. Several artists here — Klinger for example — vacillate all over the dial from academic to radical. Munch simply broke the dial. His disdain for normal technique and finish, his love of long, somewhat slurpy brush strokes that were more stained than painted, made all the difference. They enable him to give new voice to the rawest emotions, to be dramatic without sentimentality, and to fuse process, subject and content.

Revealing the context of the outer Munch, this extraordinary show only intensifies our appreciation of the inner one, by making his emotional honesty and his radical approach to painting all the more obvious and undeniable.

“Becoming Edvard Munch” opens Saturday and continues through April 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago, 111 South Michigan Avenue. Dated and timed tickets are required for admission: (312) 443-3600 or artinstituteofchicago.org. The show does not travel.

Monday, February 23, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Pages

Dreaming

About Me

- Theresa Williams

- Northwest Ohio, United States

- "I was no better than dust, yet you cannot replace me. . . Take the soft dust in your hand--does it stir: does it sing? Has it lips and a heart? Does it open its eyes to the sun? Does it run, does it dream, does it burn with a secret, or tremble In terror of death? Or ache with tremendous decisions?. . ." --Conrad Aiken

Followers

Facebook Badge

Search This Blog

Favorite Lines

My Website

Epistle, by Archibald MacLeish

Visit my Channel at YouTube

Great Artists

www.flickr.com

This is a Flickr badge showing public photos from theresarrt7. Make your own badge here.

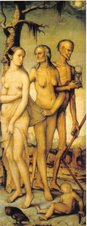

Fave Painting: Eden

Fave Painting: The Three Ages of Man and Death

by Albrecht Dürer

From the First Chapter

The Secret of Hurricanes : That article in the Waterville Scout said it was Shake- spearean, all that fatalism that guides the Kennedys' lives. The likelihood of untimely death. Recently, another one died in his prime, John-John in an airplane. Not long before that, Bobby's boy. While playing football at high speeds on snow skis. Those Kennedys take some crazy chances. I prefer my own easy ways. Which isn't to say my life hasn't been Shake-spearean. By the time I was sixteen, my life was like the darkened stage at the end of Hamlet or Macbeth. All littered with corpses and treachery.

My Original Artwork: Triptych

Wishing

Little Deer

Transformation

Looking Forward, Looking Back

Blog Archive

-

▼

2009

(273)

-

▼

February

(18)

- Haiku #132

- Haiku #131

- Haiku #130

- Haiku #129

- Haiku #128

- This day

- Haiku #127

- Museum Ephemera

- A good one

- Haiku #126

- Haiku #125

- 25 Books of Poems and 1 Book of Stories that Made ...

- Munch Exhibit, II

- Edvard Munch Exhibit

- Fifteen Albums

- AWP in Chicago

- Mysterious Life of the Heart III. Some remarks I ...

- The Mysterious Life of the Heart, II

-

▼

February

(18)

CURRENT MOON

Labels

- adolescence (1)

- Airstream (7)

- Alain de Botton (1)

- all nighters (2)

- Allen (1)

- altars (1)

- Angelus Silesius (2)

- animals (1)

- Annie Dillard (1)

- Antonio Machado (2)

- AOL Redux (1)

- April Fool (1)

- Archibald MacLeish (1)

- arts and crafts (55)

- Auden (1)

- awards (2)

- AWP (2)

- Bach (1)

- Basho (5)

- Beauty and the Beast (1)

- birthdays (1)

- blogs (5)

- boats (2)

- body (2)

- books (7)

- bookstores (1)

- Buddha (1)

- Buddha's Little Instruction Book (2)

- butterfly (4)

- buzzard (2)

- Capote (4)

- Carmel (1)

- Carson McCullers (1)

- cats (15)

- Charles Bukowski (1)

- Charles Simic (2)

- Christina Georgina Rossetti (1)

- church (2)

- confession (1)

- Conrad Aiken (1)

- cooking (5)

- crows (1)

- current events (2)

- D. H. Lawrence (3)

- death (6)

- Delmore Schwartz (4)

- detachment (1)

- dogs (7)

- domestic (3)

- dreams (21)

- Edward Munch (4)

- Edward Thomas (1)

- Eliot (3)

- Eliot's Waste Land (2)

- Emerson (2)

- Emily Dickinson (10)

- ephemera (1)

- Esalen (6)

- essay (3)

- Eugene O'Neill (3)

- Ezra Pound (1)

- F. Scott Fitzgerald (1)

- fairy tales (7)

- Fall (16)

- Famous Quotes (16)

- festivals (2)

- fire (5)

- Floreta (1)

- food (1)

- found notes etc. (1)

- found poem (2)

- fragments (86)

- Frida Kahlo (1)

- frogs-toads (4)

- Georg Trakl (1)

- gifts (1)

- Global Warming (1)

- Gluck (1)

- goats (1)

- Goodwill (1)

- Great lines of poetry (2)

- Haibun (15)

- haibun moleskine journal 2010 (2)

- Haiku (390)

- Hamlet (1)

- Hart Crane (4)

- Hayden Carruth (1)

- Henry Miller (1)

- holiday (12)

- Hyman Sobiloff (1)

- Icarus (1)

- ikkyu (5)

- Imagination (7)

- Ingmar Bergman (1)

- insect (2)

- inspiration (1)

- Issa (5)

- iTunes (1)

- Jack Kerouac (1)

- James Agee (2)

- James Dickey (5)

- James Wright (6)

- John Berryman (3)

- Joseph Campbell Meditation (2)

- journaling (1)

- Jung (1)

- Juniper Tree (1)

- Kafka (1)

- Lao Tzu (1)

- letters (1)

- light (1)

- Lorca (1)

- Lorine Niedecker (2)

- love (3)

- Lucille Clifton (1)

- Marco Polo Quarterly (1)

- Marianne Moore (1)

- Modern Poetry (14)

- moon (6)

- movies (20)

- Muriel Stuart (1)

- muse (3)

- music (8)

- Mystic (1)

- mythology (6)

- nature (3)

- New Yorker (2)

- Nietzsche (1)

- Northfork (2)

- November 12 (1)

- October (6)

- original artwork (21)

- original poem (53)

- Our Dog Buddha (6)

- Our Dog Sweet Pea (7)

- Our Yard (6)

- PAD 2009 (29)

- pad 2010 (30)

- Persephone (1)

- personal story (1)

- philosophy (1)

- Phoku (2)

- photographs (15)

- Picasso (2)

- Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1)

- Pillow Book (5)

- Pinsky (2)

- plays (1)

- poem (11)

- poet-seeker (9)

- poet-seer (6)

- poetry (55)

- politics (1)

- poppies (2)

- presentations (1)

- Provincetown (51)

- Publications (new and forthcoming) (13)

- rain (4)

- Randall Jarrell (1)

- reading (6)

- recipes (1)

- Reciprocity (1)

- Richard Brautigan (3)

- Richard Wilbur (2)

- Rilke (5)

- river (5)

- river novel (1)

- rivers (12)

- Robert Frost (2)

- Robert Rauschenberg (1)

- Robert Sean Leonard (1)

- Robinson Jeffers (1)

- Rollo May (2)

- Rumi (1)

- Ryokan (1)

- Sexton (1)

- short stories (13)

- skeletons (2)

- sleet (1)

- snake (1)

- Snow (24)

- solitude (1)

- spider (2)

- spring (1)

- Stanley Kunitz (1)

- students (2)

- suffering (4)

- suicide (2)

- summer (20)

- Sylvia Plath (2)

- Talking Writing (1)

- Tao (3)

- teaching (32)

- television (4)

- the artist (2)

- The Bridge (3)

- The Letter Project (4)

- The Shining (1)

- Thelma and Louise (1)

- Theodore Roethke (16)

- Thomas Gospel (1)

- Thomas Hardy (1)

- toys (3)

- Transcendentalism (1)

- Trickster (2)

- Trudell (1)

- Ursula LeGuin (1)

- vacation (10)

- Vermont (6)

- Virginia Woolf (1)

- Vonnegut (2)

- Wallace Stevens (1)

- Walt Whitman (8)

- weather (7)

- website (3)

- what I'm reading (2)

- William Blake (2)

- William Butler Yeats (5)

- wind (3)

- wine (2)

- winter (24)

- wood (3)

- Writing (111)

- Zen (1)

No comments:

Post a Comment